There are two common attitudes prevailing towards the 1914 Christmas truce – on the one hand it is sentimentalised as in the recent Sainsbury’s advert; on the other it is discounted as largely meaningless, if it even happened at all. Neither view takes any account of the wider context of the truce and assumes that it lasted a few hours (if at all).

The Sainsbury’s advert shows the truce as a brief interlude – not much mud in sight and remarkably well-scrubbed soldiers on both sides!

The advert has provoked a response from military historian Mark Connelly. This ‘expert’ claims that the truce was limited to ‘a couple of battalions’ and amounted to nothing more than a ‘day-off’ for a few soldiers.

A consensus seems to have developed that there is little or no documentary evidence of the truce. The Guardian recently reported the ‘discovery’ of a letter from a participant as if there were few other such letters. In fact, in 1984 a book called ‘Christmas Truce‘ by Malcolm Brown & Shirley Seaton was published. This drew extensively on interviews with participants, letters, diaries and regimental histories to give a full picture of events around Christmas 1914 – plenty of photos taken at the time as well. It even quotes the letter from Major-General Cotgrave that the Guardian reports as ‘never before seen’ until this month. This book was republished in 1994 and 2001. The authors made a film for the BBC in 1981 . The book is currently out of print but good second-hand copies can be bought online for less than £1 (plus postage). Well worth getting hold of.

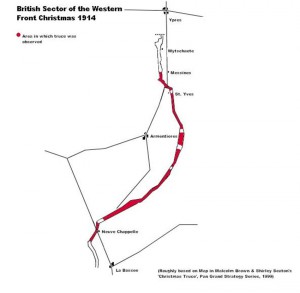

Brown & Seaton show that the truce, while not universal along the western front, did take place over at least two-thirds of the almost 30 mile stretch of the front occupied by British troops in Belgium and northern France. Letters and diaries tell us that troops from over 50 battalions of the British army fraternised with German troops along the front. Some of the German troops had spent time in England before the war and spoke English. It seems that among the extraordinary events of Christmas 1914, one British soldier got a haircut from his pre-war German barber!

The truce began in most places on Christmas Eve and extended almost everywhere into Boxing Day, even though most soldiers had returned to their respective trenches. There was very little fighting before New Year. In many places there was very little fighting through January. Some places saw very little fighting through February. In at least one place the unofficial truce went on to the end of March – just before Easter 1915, when there were further attempts at fraternisation. Similar explicit events are also recorded in November 1915 and once again at Christmas that year.

Live and let Live

But the events of Christmas 1914 formed part of a wider pattern that began in the autumn of 1914 and went on well into 1915 and in some respects even longer. Throughout this time there were many unofficial truces and tacit agreements between troops on both sides to avoid killing each other. Books about the war allude to what came to be called ‘live and let live’. This is most thoroughly documented in a book called ‘Trench Warfare 1914-1918‘ by Tony Ashworth first published in 1980. It was re-published in 2000 in the same series as the Brown & Seaton book – bizarrely called ‘Pan Grand Strategy’. It draws on similar sources to that book. Like that book, it is also out of print but widely available cheaply secondhand online.

Ashworth explains that the common picture of the trenches as two implacably hostile front lines several hundred yards apart with an extensive area of no-mans land between them, is by no means the full story. Although this was the case in some places, it certainly wasn’t the norm. In many places the trenches were less than 100 yards apart, even as little as 50 yards apart. In some cases 10 yards. There is even one instance of the two trenches being in the same building. The proximity of the front-line troops facilitated direct and indirect forms of communication. Away from the main set-piece battles many sections of the front-line saw little or no fighting. In these areas, usually occupied by what Ashworth calls ‘non-elite’ troops, relationships built up between soldiers in the opposing trenches.

They came to understand that they had a mutual interest in keeping things as quiet as possible. If British troops could be confident that German troops would reciprocate then they would avoid killing them. This resulted in informal truces, suspensions of sniping, ritualised firing of weapons (e.g. firing weapons to look like combat was underway, whilst minimising opposition casualties) and routinised firing of weapons (e.g. always firing at the same time of day – breakfast time was often commonly avoided!). Ashworth describes how soldiers in the trenches were even able to get the help of artillery batteries in pursuing these tactics.

In these ‘egg and chips’ sectors (as the ‘Tommies’ named them), which Ashworth estimates were somewhere between a third and one half of the British-German frontline, the exchange of peace rather than the exchange of death became the norm. Of course such behaviours, which spread through the combatants on both sides, sometimes even influencing front-line officers, were certainly not officially sanctioned by the ‘brass’. In fact they were a complete anathema to military strategy on both sides which called for, outside of major offensives, a relentless war of attrition in the trenches. As Ashworth rightly points out, ‘Truces were usually tacit, but always unofficial and illicit’.

Faced with the widespread phenomenon of ‘live and let live’ military commanders adopted a number of strategies to build what they called ‘offensive spirit’ among their troops. Night patrols in no-mans land were introduced, although at times these were carried out in the least-threatening manner possible by both sides. Warfare was bureaucratised, with frontline officers having to make written reports to HQ every few hours on what they had achieved in the ‘war of attrition’, though these were often falsified or exaggerated. The ‘brass’ even produced a pamphlet for officers called ‘Am I offensive enough?’ which was explicit propaganda designed to combat ‘live and let live’ type behaviours. Needless to say it was widely ridiculed.

However, less easy to incorporate into ‘live and let live’ strategies were trench raids, small-scale, stealthy night attacks on opposing trenches. These vicious encounters, where assault groups were encouraged to use bayonets, hatchets and shovels as well as pistols and grenades to butcher their opponents in hand-to-hand fighting, were explicitly designed to spread fear amongst opposing troops and to break any tacit truces between the lines. Along with the horrors of the major offensives in 1916 and the use of gas, which intensified the brutalisation of the combatants, trench raids were a useful tool for the ‘brass’ on both sides in destroying cooperative behaviours between front-line troops.

Balls to War

So was there a football match on Christmas Day 1914? Almost certainly not in any formal sense, although there are sufficient first-hand reports of informal kickabouts that we can be sure they must have taken place. We have to remember that in many places no-mans land was pitted with shell holes – not ideal for playing football. Interestingly several first-hand accounts mention the idea of spending the days after Christmas Day levelling an area of no-mans land and holding a formal football game on New Years Day. This gives some idea of the scope which at least some soldiers envisaged for the truce. A good visual account of the events is given in Heathcoate Williams video, ‘Balls to War: a Sports Report from 1170 A.D. to the Present’.

So there was a truce at Christmas 1914 and there was extensive fraternisation between troops from both sides over large sections of the front for several days and in some cases for several months. Many of the participants record it in terms which suggest they saw it as one of the most significant events of their lives. It was not merely an aberration or a ‘miracle’ as it is often presented; in fact it formed part of a far-wider ‘live and let live’ response by troops on both sides to the situation they found themselves in during 1914 and 1915. Despite the efforts of the brass on both sides to stamp out these survival strategies, clandestine cooperation between front-line troops continued throughout the war in a number of different forms. Furthermore, the implicit refusal of ‘live and let live’ was echoed again in the more explicit mutinies, strikes and mass desertions that ensured the war became no longer tenable on the eastern front in 1917 and were a major contribution to the end of the war on the western front in 1918.

One thing we can be sure of is that it wasn’t much like the Sainsbury’s advert.