The momentous EU referendum has cast a long shadow over politics this summer. Those architects of austerity, Cameron and Osborne, have gone from office and the former has announced he is stepping down as MP too. The Tories have a new leader but no idea of what Brexit actually means and it might take years before Britain can go it alone. The effect on Labour has been, if anything, even more tumultuous.

Labour in crisis

While the effect of the leave result on the Conservative party was entirely predictable, no-one could have foreseen the crisis which has engulfed Labour since 23 June. Almost as soon as result was known, resignations from the shadow cabinet began, first Hilary Benn and then nearly all the rest of the frontbench team.

A section of the Parliamentary Labour Party, right-wing Blairites, had never accepted Corbyn’s leadership victory in 2015 and were looking for any excuse to topple him. They hoped he would resign after a vote of no confidence was supported by 170 MPs, with 40 against. The stage was set for a summer of internecine rivalry between Corbyn and his supporters and the vast majority of MPs who want him to quit, including two cases in the High Court.

Not only has Corbyn refused to resign, he has gone on the offensive, speaking at rallies up and down the country organised by Momentum, a campaign group set up after he became leader. His power base lies not in the PLP but in the party membership which mushroomed since he became leader. Over 130,000 members had joined since the shadow cabinet resignations, almost all pro-Corbyn. Labour’s ruling body, the NEC, said they would be ineligible to vote in the upcoming leadership election.

Instead it decided “registered supporters” could vote for the next leader if they paid a one off fee of £25. 184,541 people subsequently paid this during a two day window in July, more than the entire Tory Party membership. Labour now has more members than any political party in Western Europe. The result of the leadership contest between Corbyn and Owen Smith will be announced at the party conference on Saturday 24 September. An overwhelming victory for Corbyn is widely expected.

Corbyn and the left

Since Corbyn became leader all sorts of groups and sects on the far left have flocked towards Labour. These include the Socialist Party – which in its former guise as Militant infiltrated Labour in the eighties – the SWP, the Communist Party, Left Unity and Trotskyist grouplets like Workers Power, Socialist Resistance and Alliance for Workers’ Liberty.

Unsurprisingly all these organisations view this as an opportunity to further their aims. Trotskyists in particular emphasize the importance of taking over Labour. Nevertheless there are at most just a few thousand members of these parties, so the vast majority of recent recruits to Labour are new to party politics.

What is surprising, however, is the number of anarchists, libertarians and activists who’ve turned to Labour. Disabled People Against the Cuts announced: ” Disabled people need Labour to have a leader that will fight the evil that this Tory government will do.” Social media buzzed with delight following Corbyn’s election victory last year and that has only heightened since his leadership came under threat. It didn’t take long for the Facebook group Anarchists for Jeremy Corbyn to appear.

In Corbyn – anarchists missing the point, Sabcat, the workers’ coop based in the West Midlands stated: “Corbyn is arguing for and creating a movement based on improving the conditions of working class people and that has to be the point of politics”. In a piece on Freedom’s website called The end of dogma: #KeepCorbyn as a transitional demand, Daniel Dawson said: “To refuse to support Corbyn during this coup is to ignore the direction of class struggle. This is not a call to join the Labour Party, while many might and should if they see fit, but merely to accept that class struggle right now has a clear invested interest within it.”

Corbyn and animal rights

Animal Aid took the unprecedented step of praising Corbyn as an “animals’ champion” after he became Labour leader in 2015. The other three candidates endorsed official Labour polices against hunting with hounds and the badger cull but in contrast he had signed a number of Early Day Motions and sponsored at least three, against the use of wild animals in circuses, to reduce the number of animals used in experimentation, and to stop the use of primates in vivisection.

In addition Animal Aid said he had supported other campaigns “including calling for a ban on snares and demanding government action to stop live exports” and published a lengthy quote from him criticising McDonald’s during the McLibel trial. It also pointed out that he is a vegetarian.

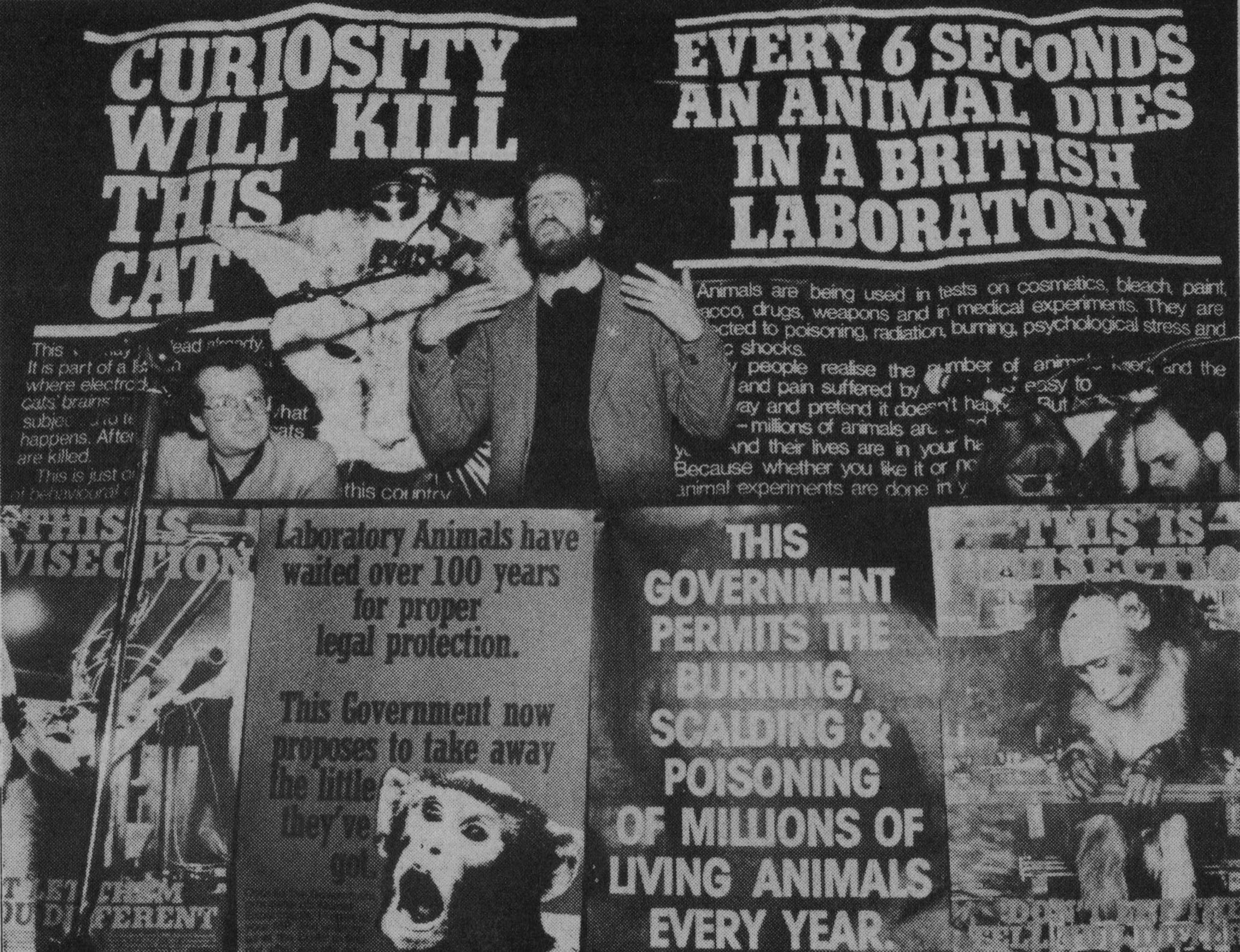

Corbyn’s involvement in animal rights goes back to the eighties. In 1983 a march was held against Biorex Laboratory in Islington, London, where he had recently won a seat in parliament. He and another MP, Chris Smith, spoke at the rally afterwards at Islington Town Hall. The event was organised by the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection which had just moved its HQ to the borough as the local council had passed an Animal Rights Charter. Three years later when the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act – dubbed the Vivisectors Charter – became law, Corbyn was one of only 20 MPs to vote against it.

Corbynism in perspective

The unlikely rise of Corbyn didn’t happen by accident. The conditions for it were laid by the global financial crisis and public dissatisfaction with mainstream politics over scandals such as MPs’ expenses, phone hacking and historical child sexual abuse allegations against people in power. Right wing populism, which has gained ground across Europe, is based on national identity, a rejection of the EU and anti-immigrant rhetoric. Left wing populism, on the other hand, focuses on tax evasion by the super rich and corporations, zero hours contacts, rising inequality and lack of investment in public services such as the NHS.

Labour’s defeat at the 2015 general election, when the austerity-lite agenda pursued by Miliband and Balls was rejected by the electorate and it seemed the party had run out of ideas, set the stage for Corbyn’s ascent. He won with nearly 60% of the vote – a larger majority than Tony Blair’s in 1994. This was partly due to a rule change under Ed Miliband in which those who supported Labour’s aims and values could join the party as “registered supporters” for £3 and be entitled to vote in the election.

Corbyn’s record as leader of the Opposition was mixed. Labour won a number of by-elections and four mayoral contests but its share of the vote in May’s local elections was only 31% – far short of what is required to form a government – and it was beaten into third place by the Tories in Scotland. Then came the EU referendum campaign in which Corbyn’s performance was denounced as “lukewarm” by some of his critics. In fact he had, like his political mentor Tony Benn, always been a staunch opponent of the Common Market and later the EU, voting against membership in the first referendum in 1975 and again in Parliament in 1992 and 2009.

Last year Corbyn declared: “I would advocate a No vote if we are going to get an imposition of free market policies across Europe.” Yet shortly afterwards he co-signed a letter with foreign secretary Hilary Benn, promising to call for remain regardless of the outcome of Cameron’s negotiations with the EU. Corbyn, always portrayed as a conviction politician, put party unity before his principles. Had he chosen to campaign for exit on socialist and internationalist grounds, the result might have been different and his opponents wouldn’t have had the ammunition to attack him as weak and indecisive.

How much of an animal rights advocate is Corbyn?

Jeremy Corbyn has become a symbol, a cipher onto which people can project their hopes and dreams. Faced with years of Tory austerity and an opposition that seemed floundering and demoralised, he represents a form of redemption. His acolytes appear to regard him with an almost religious fervour at times. There is definitely a flavour of a messianic cult about the mass rallies that cheer his speeches, despite the self-effacing and diffident demeanour he projects.

A few days ago Ronnie Lee posted a meme on Facebook with photos of Corbyn and his leadership rival headed: “One of these men is against animal testing, the other is Owen Smith.” The latter was wearing a Pfzier badge because he had been a “chief lobbyist for Pfizer. Pfizer was and is one of the worst companies in the world for carrying out cruel and lethal experiments on animals.”

That is correct but an early day motion signed by Corbyn and McDonnell in 2014 asked ministers to “ensure that the UK continues to be a world leader in science and pharmaceuticals research and development” following an attempted takeover of AstraZeneca by Pfizer. In July this year a spokesperson for Corbyn said there was a need “to fund a major increase in publicly funded research, which can be contracted to private research organisations, including the medical research needed to address pressing medical issues like dementia.”

While that does not necessarily mean Corbyn is pro-vivisection, it casts doubt on claims he’s opposed to all animal research. I grew up in Islington and was deeply involved in the struggle against Biorex. After the 1983 march, the BUAV walked away and it was left to Islington Animal Rights who fought a high-profile campaign against the laboratory. Despite being in his backyard, I don’t recall Corbyn attending a single protest or meeting. In 1989, however, Biorex closed down and it was a major victory.

Corbyn has made a scant contribution to the struggle against animal experiments since the eighties. Other than the EDMs outlined above by Animal Aid, the only reference I have seen is an Oxford Union Debate many years ago in which he discussed socialism and was asked about the morals and ethics of the Cooperative Bank. He praised the bank’s ethical policy against the arms trade and “experiments on animals.” Except that isn’t true; it won’t invest in testing for cosmetics and household products but it has always said medical research involving animals is justified.

Kerry McCarthy, environment secretary in Corbyn’s first shadow cabinet, caused controversy by suggesting in an interview with VIVA! that “meat should be treated in exactly the same way as tobacco, with public campaigns to stop stop people eating it”. McCarthy claimed she was vegan and Corbyn received plaudits in certain AR quarters for appointing her. When asked about her statement, however, he said his vegetarianism was a personal matter.

McCarthy herself backtracked a few months later in an article entitled I am not a mad, vegan, lefty Corbynista on fginsite.com. She insisted her remarks were “driven by nutritional concerns, not an animal welfare agenda”, instead claiming people required “the information they need to make the right choices” about eating meat. She also admitted wearing wool and buying meals containing meat for her family and said Labour could re-consider its opposition to the badger cull “If the evidence shows culling is the best way to curb TB”.

McCarthy returned to the badger cull in a recent Huffington Post blog. Corbyn, she says, accused the government of “gassing badgers” during the EU campaign whereas they were being shot. This is one of many criticisms she makes of Corbyn’s leadership abilities but these must be viewed through the prism of her resignation from his shadow cabinet in June.

It is clearly an exaggeration to describe Corbyn as an “Animals Champion” based on the evidence of his political career. He has done more than many MPs but only because most do little or nothing at all. If he really believed in animal rights, then surely he would have pressed for such a policy to be issued since he became leader but nothing has been heard.

When Labour was in power from 1997-2013 it reneged on nearly all its pre-election promises on animal protection, allowed Barry Horne to die on hunger strike, propped up Huntingdon Life Sciences and funded Oxford University to the tune of £100m, enabling it to build an animal research laboratory. AR activists were targeted with draconian laws and harsh prison sentences, especially anti-anti-vivsectionists. Corbyn, as far as I know, has never spoke out against this. It would have been very different had it been the peace movement.

Finally – and this has to be said – if he is really is a champion for animals, why hasn’t be gone vegan after being vegetarian for decades?

Corbyn: an anarchist viewpoint

The last 12 months has seen a resurgence for the left in this country in a series of well attended meetings and rallies, some in the thousands. Ideas are being debated and people energised. Corbyn is the focal point for what has been called a “new politics”, based on the mass membership of the Labour Party and an anti-austerity agenda.

It would be easy as an anarchist to say this is a waste of time. But as Adam Barr writes in The current crisis and the rise of the Corbyn dogma, “to ignore or dismiss the great number of people signing up to the Labour Party to support him and the politics he represents would be a wasted opportunity.” The fact Labour has been the vehicle for this upsurge, not the non-state left, says a lot about the state of the latter.

The reasons for the weakness of the libertarian left complex but a major cause is the increase in state repression over the past 10 years. This has had an enormous impact on animal rights and spread to other social movements as well, for example anti-austerity activists who were met with police brutality, arrests and imprisonment in 2010-11.

Now, ironically, some of those activists and groups have joined Labour and are campaigning for Corbyn. They are trusting the same state – party even – that was once their enemy to transform society for the better, because the leader and the team around him are different. This sounds reasonable but the problem is we don’t have a presidential system, we have party government. Corbyn can only become prime minister with MPs winning seats at a general election.

This simple fact seems to be lost on some of his supporters, one of whom recently expressed anger on social media after the PLP asked her to come to a meeting! It would appear they think electing Corbyn as leader is all that’s required. Far from it. Whoever wins the contest, the other side won’t meekly accept the decision. Are new recruits prepared to sacrifice months, if not years of their lives in an internal party struggle to deselect hostile MPs and replace them with ones sympathetic to Corbyn?

All this is nothing new. After Thatcher’s victory in 1979 Labour was thrown into upheaval. The left blamed the Wilson government of the seventies for selling out and vowed to turn Labour into a socialist party. Michael Foot, cut from the same cloth as Corbyn, became leader and left wing councils came to power in London, Liverpool, Sheffield and elsewhere. Foot spoke to huge assemblies up and down the country, including 200,000 at a CND rally in London. Nevertheless in 1981 28 MPs from the right of the party deserted to form the Social Democratic Party and two years later Labour was routed as the Tories gained a 144 seat majority.

As Adam Barr says:

The whole point of anarchist politics is that liberation is won through the self organisation of the working class and other oppressed groups through direct action, strikes and agitation. To give up on that now, for the hope of reforming the Labour Party to achieve unspecified ‘transitional demands’ doesn’t make much sense. Tactics such as direct action have time and again won concessions from the state that have immeasurably improved working peoples lives. More importantly it has done so in a way that doesn’t politically disempower people but builds solidarity and working class power.

Some will argue it is worth the sacrifice of internal politics if it offers the hope of a genuinely leftwing alternative to the Tories. Surely even the slightest prospect of a socialist government with Corbyn as PM is worth fighting for?

History proves otherwise, however, as time and time again such dreams have been dashed. At the start of 2015, leftists were jubilant at the election of the Syriza government in Greece on an socialist platform. Within months the party capitulated to to a new round of austerity that was as harsh or even harsher than that it had inherited. A few years earlier the socialist government in France had promised to stand up for working class people. This year has seen strikes and riots as the same government tries to dismantle the welfare state and legislation protecting worker’s rights.

This is nothing new. It goes all the way back to the 19th century when universal suffrage allowed mass parties of the left to develop. Probably the first of them was in Germany where Marx and Engels exhorted workers to join and vote for the SPD to carry forward a programme of state socialism. The party was in government for years but began “a slow and slippery decent into reformism, hidden behind radical rhetoric.” In 1914 it called for Germany’s entry into the First World War (as did Labour in this country).

The anarchist Mikhail Bakunin summed this up well: “the workers… send common workers… to Legislative Assemblies… The worker-deputies, transplanted into a bourgeois environment, into an atmosphere of purely bourgeois ideas, will in fact cease to be workers and, becoming Statesmen, they will become bourgeois… For men do not make their situations; on the contrary, men are made by them.”

The inevitable failure of leftwing parties when in power is often couched in terms of betrayal, a “sell out” narrative of politically compromised leaders and parties falling victim to forces beyond their control. What usually happens though is something quite different: the parties and their leaders actually buy into the idea of managing capitalism in order to transform the state into a vehicle for socialism.

A socialist party in government must rely on a capitalist social order and economy for tax revenue and to borrow on the bond markets from financial institutions. Either way the state has to ensure conditions are right for business to grow, such as protecting private property, regulating capital flows, incentivizing certain companies over others, etc.

In the case of Greece, just one month after Syriza came to power it agreed a new round of austerity measures and riot police were used to attack demonstrators. Whatever its political complexion, the state always maintains a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, both domestically and internationally.

Conclusion

In the title I asked whether we should care about Labour’s turmoil. With no sentimental attachment to the party or its political tradition, I would say no. But what we should care about is the ordinary people who’ve felt inspired to get involved in politics for the first time.

Whatever happens to Labour in the next few years there will inevitably be disappointment, whether that’s the defeat of Corbyn and the left or its inability to live up to the hopes of its supporters – or both. As anarchists we have to ensure our ideas and beliefs are in the mix at such a time of ferment and opportunity. Rather than people turn away from radical change because they feel betrayed or let down by politicians, it is up to us to present an alternative narrative based on hope, real hope.

As Red and Black Leeds’ article This is not our victory so stirringly puts it:

So rather than place our faith in politicians to make things better for us, we choose instead to find hope in one another. It is not grand speeches by would-be leaders that inspire us, but the words and actions of ordinary people coming together, whether in the form of strikes and occupations or the many smaller acts of resistance and solidarity that make our day-to-day lives bearable. The false hope offered by Jeremy Corbyn and the like leads only to disappointment, disillusionment and despair. Real hope is sometimes hard to find, and real change is harder still, but we have to be honest with ourselves and one another, and face up to the realities of our collective situation. We have a long way to go to bring about revolutionary change, but the struggle starts in the here and now.

https://freedomnews.org.uk/the-current-crisis-and-the-rise-of-the-corbyn-dogma/

https://wearetherabl.wordpress.com/2015/09/11/this-is-not-our-victory/

https://network23.org/redblackgreen/2015/05/05/why-labour-cant-be-trusted-1-the-working-class/

https://network23.org/redblackgreen/2016/06/30/why-labour-cant-be-trusted-2-animal-protection/

Leave a Reply