Review

The Social, Political and Historical Contours of Deportation

Bridget Anderson, Matthew J. Gibney & Emmanuel Paoletti (Editors) .

This slim, but wide ranging collection of essays on the theme of deportation, as the editors state in the introduction, examines the effects of deportation not just on those expelled from one state to another, but also the effects that the process of deportation has on those public bodies who are involved with it. Unfortunately, due to cost and the fact that this book won’t be borrowable outside academic libraries, practitioners in the field often won’t have the benefits of the insights contained within, so with this in mind I will attempt a critical explication from activist’s point of view, that at least in theory is more accessible.

Le centre de rétention administrative du Mesnil-Amelot au nord de Paris Stéphane de Sakutin AFP/Archives

One piece that captures a ongoing wider debate of what point resistance to the system turns into collaboration with it is “Negotiations Deportations: Ethnography of the Legal Challenge”. In this piece, Nicolas Fischer does not enter the debate head on but instead provides a analysis of the peculiar way that legal challenges are mounted to deportation orders within French detention centres (Centre de Retention) he in particularly focuses on one charity’s part in the process.

The French detention-deportation system differs from the UK’s in many ways. First of all, the maximum length of detention is 32 days, compared with the unlimited time that migrants can be held in the UK. The detention centres themselves, though subject to national standards are administered at the local level. Most importantly, and what is the focus of this essay, is that there are organisations who advocate for the prisoners, embedded within the centres themselves., These groups are often outspoken critics of many of the decisions made both in the case of individual cases at the policy level as well.

The main charity, Cimades had been involved with the detention centres since they came into ‘regularised’ existence in 1984. Cimades, though had been active in refugee camps since the organisation’s formation in 1939. As well as working within refugees camps during the occupation, they assisted Jewish people escape the Nazis.

However, I would argue that we should see Cimades as both as a critic and a collaborator of the system.

Cimades workers thought of “each legal action taken against an allegedly abusive deportation order was commonly presented as a “fight” against state officials, ending up in a “defeat” or “victory”[1]. A seemingly oppositional stance to the system then? Fischer sees though that the opposition runs alongside tacit support for the system, encapsulated by this quote from a Cimades lawyer directed towards a inmate with a ‘weak case’:

“I am sorry, but you have to understand that there is the law and a civil service to enforce it. We at Cimades disagree with that law, but all the same, I have to do something that is compatible with it if I want to help…”[2]

In all the interviews that the lawyers had with the detainees, they ran through a check list of the most obvious legal reason to stop the deportation, for example; Were they seeking political asylum? Did they have family who were resident in France? At the end of one legal advice interview, the detainee suggested that he may physically resist his deportation. The lawyer agreed that he could do that, though also warned him that could lead to prosecution. Here for me is the ‘activist’s dilemma’: Once you enter the system, the advice and assistance that you can offer is prescribed by the system you are fighting. Is your participation a fig-leaf which is necessary for its existence? Certainly, there appear to be clear cases where NGO’s have chosen to administrate with elements of the deportation system e.g. “The Voluntary Returns Scheme” or “Pre-Departure Family Accommodation” where the line has clearly been crossed.

However, the question this essay raises is whether even the pragmatic engagement with the Deportation Judicial framework e.g. appeals, judicial reviews, even while it makes the apparatus less efficient in terms of speed and number of deportations, makes the system seem more acceptable.

The other option fighting on a purely oppositional and confrontational basis has also profound problems. Normally poorly resourced, any response to issues on the ground is often piecemeal and erratic. When you do become effective you will be liable to prosecution, state violence and imprisonment . The “protest method” often seems tokenistic and ineffective, even to those (or especially so in fact) to those committed to it. Of course, there are examples of good practice, for example in France where Calais Migrant Solidarity have managed (more or less) to maintain a constant presence and oppositional stance to state repression.

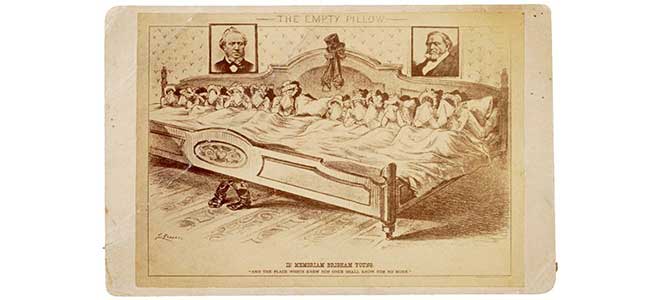

In Muslims, Mormons and U.S Deportation and Exclusion Policies, Deirdre M. Moloney writes about a early example of what we would call Islamophobia; How some Muslims were effectively excluded from entering the United States due to their “un-American” way of life. This was not because they were thought of as potential terrorists at the time, but on the pretext of their (purported) practice of polygamy, or even their mere refusal to condemn it outright. This chapter shows how immigration officials used the official view of polygamy as a threat to the well being of the nation to exclude non-Christians from entering the country.

We see how a particular (negative) attribute – polygamy – was erroneously attached to all, in the same way that Bolshevism was used against Jewish emigrants at the beginning of the 20th century, as ‘fundamentalism’ is used today to exclude Muslims.

In 1883, a group of Mormons migrated from Switzerland to the United .States. At first, officials tried to exclude them based on their poverty, as ever, seen as a legitimate reason to punish by the state. However, despite concerns that the Mormons were “being imported to the United States to strengthen the ranks of polygamists”[3] no specific legislation existed at that point to exclude them on that basis. By 1891, that had changed, with a new immigration law which included the provision to refusal entry solely based on polygamy.

Polygamy became the ‘catch all’ which also stopped entry from the Muslim[4] Ottoman and then Turkic Empire. In fact, all Muslims were excluded on this basis, even though it was unlikely that many actually practiced polygamy. This caused a battle between Trade on one hand, and Immigration Officials on the other. The former, who were eager to allow migrants from the Ottoman empire permission to enter, as had been agreed as part of a bilateral economic agreement, and on the other hand immigration officials who appeared to want exclude them at all costs as a cultural (or deviant) threat. Even though it was evident that they most were unlikely to engage in polygamy, merely refusing to condemn what their religion allowed was sufficient grounds for exclusion. Moloney draws an obvious comparison with the way that 13,000 Arab and Middle Eastern men were deported post 9/11 despite no connection with ‘terrorist’ organisations.

Moving on to contemporary Islamophobia, Michela Sembron in Between Routine Police Checks and ‘Residual Practices of Expulsion Power’: The Impacts of the Anti-Terrorism Law on Phone Centres and the Resistance of Owners. An Italian Ethnography in the ‘Emergency Season’ examines one element of the indiscriminate backlash post-9/11 against Muslims was felt all over the world. In Italy, one of the terrorists who planned a attack in 2005 was arrested in a ‘Phone Centre’ in Rome. This so called, Emergency Legislation was introduced to monitor and regulate and in effect persecute the owners and users of such centres.

Phone and Internet centres (shops as they are referred to in the UK) are a hub for new migrants. So, when the various branches of Italian Polizia failed to detect any terrorist activity, they quickly realised that it may instead a good place to search for unregulated migrants. The powers of surveillance, licensing and search provided by the emergency terrorist legislation was soon fully applied to the harassment of migrants.

One customer’s practical experience of the legislation is described:

“I saw five policemen entering into the phone centre. They immediately asked everyone to stop what they were doing, including the owner and every single customer…Even people who were there just to accompany were stopped. Children too! Everyone was then asked for their ID and residence permit…No one was allowed in or out of the shop [for an hour].”[5]

This illustrates how an everyday activity, in this case communicating with your relatives, or trying to sort out a bureaucratic task can become a risky activity if you are part of the target population of such powers. This is also evident in the ‘triangulation’ of criminal stop and search, immigration and specific terrorist powers in the UK which effectively allow the state to stop anyone who looks a ‘bit foreign’ without just cause. ‘Racial’ profiling is given a new legitimacy, being of the wrong skin colour; in the wrong place are again grounds for suspicion.

Of course, as is the case in London the application of these powers were not uncontested. Shop owners evaded the surveillance aspects, and refused to check their customer’s papers on the States behalf and use remote handsets to allow people to make calls without being on the premises.

The most fascinating and troublesome chapter for me was “Deportation and the Failure of Foreigner Control in the Weimar Republic”. We are treated to an in depth and widely sourced survey of attitudes and reaction of migration in the years following the First World War and the Russian Revolution. It gives a great insight into the debate about immigration in Germany in the run up to the World War II. What’s most striking is despite a gap of almost a 100 years how similar the anti-(im)migrant rhetoric and propaganda is – along with a reluctance from even those who were sympathetic to those fleeing persecution and poverty was an unwillingness to publicly challenge it, leaving a debate skewed towards intolerance and suspicion that we are familiar with today. While national Interior Minister Rudolf Oeser described in 1923 the immigration in contemporary tabloid language as a: “…flooding of the Reich’s territory with foreigners”[6] the socialists and social democrats didn’t counter with positive arguments for immigration, though they did resist pressure for mass deportation and internment of “Ostjuden” (Eastern Jews).

Eastern European Jewish women are asked for ID cards in Berlin’s “Barn Quarter” in 1920

It hardly needs pointing out that the Weimar republic was the creaky, if relatively benevolent forerunner to the Third Reich. At some point in this essay, its apparent failure to control immigration is seemingly and dubiously implicated by the author in its collapse, and by that logic with the rise of fascism.

;

“They [Nationalists] also used stereotypes about Eastern Europeans to describe those immigrants , contributing to a dangerous and reinforcing process, in which the failures to control immigration were projected onto Eastern European Jews while anti-Semitic stereotypes imbued immigration policy with an increased threat. The Weimar state was caught in a devastating spiral: lacking an aura of authority, its critics constantly hammered at its incapacity to control immigration. In yet another dangerous cycle, critics of Germany’s lax borders assumed qualities about Jews to affirm the dangers of immigration, while at the same time, the dangers of migrants were easily translated as problems posed by all Jews. Told from this perspective, the failure to pursue policies like deportation contributed to the state’s weak sense of legitimacy(my italics).”[7]

Though Anne-marie Sammarinto also identifies the problem was caused by the failure and unwillingness by the liberal establishment to challenge the anti-Semitic/anti-immigrant rhetoric – more echoes of the present. Throughout the article there seems to be a sense that Weimar Germany’s (and Prussia’s) ineffective immigration controls are implicated in the following political crises, and therefore rise of The Third Reich. It should be said that her analysis is nuanced;. She also says herself that the figure of immigrant was commonly stereotyped as the ‘Bolshevik Jew’, even though perhaps less than 15% of German migrants were Jewish and one supposes if they were fleeing communist Russia, even less would be Bolshevik. Though even suggesting it was the popular misconception of immigration and perceived (as well as actual) lack of controls contributed to the rise of Hitler is still to me misstating the case. Let us imagine a Weimar Germany with effective immigration controls. As we see today in Greece, punitive and harsh migration controls do nothing to assuage the extreme right, rather they feed it’s rhetoric by confirming it and exaggerating the scale of the problem, distracting from the root causes of the economic crisis. It’s not hard to imagine a ‘effective’ deportation/border regime in 1920’s Germany similarly feeding the anti-Semitism of the era. I also wonder if the author’s tagging of the word ‘immigration” with ‘illegal is appropriate within the historical context, if not actually anachronistic.

“The European Parliament and the Returns Directive:The End of Radical Contestation;The start of Consensual Constraints” tells the sad story of how the European Parliament (EP) once a champion of a human

rights approach to immigration, and a voice of constraint and opposition to the European Council’s more authoritarian tendencies became it’s collaborator in the post 9/11 world. Ironically, it was the EP’s new power to legislate that it became less oppositional. The essay uses the example of the “Returns Directive” which aimed to “harmonise national conditions [within the Schengen area] dealing with the voluntary or compulsory return of irregular immigrants..as well as stipulations to issue removal directions…”[8] The author notes that in four out of the six main issues a more punitive approach was adopted. This included a 5 year ban from the EU for those forcibly removed and migrants can be detained for up to 18 months (even this unfortunately compares favorably with no time limit set by the UK).

The result of this “harmonisation” – the desperate impetus to reach an agreement – appears that the harsher approach of the more Conservative/Right-wing elements with the EU seems to have prevailed; ‘a race to the bottom’ then. Ariadna Servent’s conclusion is realistically downbeat; that the securitisation of the EP’s approach to (im)migration is set to further push aside any concern for human rights for the foreseeable future.

For those of us working at the grassroots level who see decisions made in Brussels and Westminster as remote as they are inhuman “Studying Migration Governance from the Bottom-Up” by Matthew Gravelle, Antje Ellermann and Catherine Dauvergne is a intriguing first stab at quantifying the impact that local and sub-national organisations have in the implementation of nationally decided immigration policy. They look at both “deportation” specifically and “immigration policy “in general. They compare four countries, through the study of newspaper articles. Each of the countries varies in terms of “state strength” or centralisation of power, with Australia at one end (similar to the UK’s constitution) and the US at the other end, with many powers delegated to the State level.

What’s unsurprising is that local intervention and contestation is much more common across all four countries within the specific “deportation” field than with “immigration policy” in general. This reflects the daily struggle of opposing deportations involving many local actors every day of the week, from the church, community groups and local council. These are decisions that are made about people we know. What’s more, we are painfully aware that opposing immigration policies we don’t like hasn’t had much impact, whereas with individual cases we do.

The local-national interaction is a interesting one for campaigners. Not least in the light of opinion polls that consistently show a hostility to immigration in the abstract: “…vast majorities view im migration as harmful to Britain, few claim that their own neighbourhood is having problems due to migrants”[9] I wonder if it would be possible to propose restrictive, penalising legislation if it was controlled at the local level?

This local/national division is also mentioned in Arjen Leekes and Dennis Broeders contribution: Deportable and Not so Deportable: Formal and Informal Functions of Administrative Immigration Detention”. They write that the impacts of Dutch government restrictive immigration policy: homeless and pauperized “unauthorised migrants” began to organise accommodation themselves, alongside the piecemeal services offered by the bizarre but now familiar mix of left-organisations, NGO’s and churches.

Dutch Detention Centre

However, their focus is actually on how the massive increase of immigration detention, and it’s “informal” or secondary functions”[10]. The study is wholly focused in the Netherlands, but it’s main contention that since “the number of expulsions turns out to be relatively independent of the number of migrants detained” it must fulfill other functions – can be probably applied throughout Europe. For instance, the relationship between detention and expulsion in the UK seems to have a weak correlation as well.[11] Given the expense and political controversies of detention, some other purpose must be being served. The authors suggestion are threefold: (1) deterring illegal residence (2) controlling pauperism and (3) symbolically asserting State control[12].

Migration is often portrayed in reactionary discourse as ‘out of control’. So: “The increase in immigration detention communicates the message that the State is still in control over the geographical (and social) borders that [some] citizens want maintaining.[13] It also punishes by “denouncing”[14] unauthorised migration. Incarcerating people, with, or without a criminal trial is obviously a way saying that they are a transgressor of one type of another.

‘Controlling pauperism’ is perhaps the least obvious function of immigration detention. However, Leerkes and Broeders describe a cycle where a sub-group of unauthorised migrants enter and exit the detention estate on a regular basis. They receive no welfare payments, and will never be regularised and for a variety of reasons fall through NGO safety net as well. These are the “undeportable- deportable”. Those who have picked up (normally minor) criminal records who even those who normally advocate for migrants prefer to ignore as their criminality disqualifies them from the status of the ‘deserving migrant’.

There is even a phrase for the release of such migrants: klinikeren “cobbling[15]”; onto the stoney Dutch streets. Detention “..may also be used a form of ‘relief of last resort’”[16] for this group of migrants. For instance, the authors find that local police use detention to end “public disorder disturbances that are associated with immigrant pauperism”[17]. Immigration staff said that more “undesirable aliens”[18] are imprisoned during public events like the queen’s birthday – a familiar tale of social cleansing which seems to be an integral part of every Olympics, World Cup and political summit. Even more surprisingly, and distressingly, some migrants are so impoverished and traumatised by life on the streets, that they ‘self-admit’. One respondent they interviewed said he plead guilty to offences he didn’t commit “to recover in detention from life on the streets.”[19]

They conclude that while migration is increasing a de facto criminal offence, one of the reasons why it hasn’t been incorporated fully into criminal law is for the reason of proportionality. In the Netherlands, migrants can be held for up to 18 months for “mere illegal residence”[20], this would “contrast strongly with the major crimes leading to such a lengthy [criminal] sentence”[21] . With no determined maximum length of detention in the UK results with some held as long as 8 years[22]. This can only be compared with sentences passed for offences as serious as manslaughter and armed robbery.

The final chapter “From Migrant Destitution to Self-Organization into Transitory National Communities” by Clara Lecadet gives a insight how those marginalised by immigration controls and deportation keep their identity and their dignity. The description of the organisation of this multi-national and multi-ethnic community in Mali will no doubt have resonances with those who have worked in another migrant-transit involuntary stopping points, for instance Calais.

The abandoned village of Tinzwaten, Mali maybe almost 5000 km from Calais, but the organisation of the six ruined (and repaired) houses into micro-nations e.g. Nigerian, Cameroonian, Gambian has obvious similarity with the “Pashto Jungle”, or the various “Africa House” squats in Calais. Their living arrangements in Northern Mali are harsh and after having been unceremoniously dumped in the desert by the Algerian army, they must be both exhausted and desperate. However, once in Tinzwaten, (unlike in Calais) the expelled migrants appear to be left to their own devices. No CS gassing, continual arrests beatings, confiscation of belongings that migrants suffer in “liberal” France., they procure food and cook, uninterrupted by a raid by the riot police. However, it should be said they have already passed through the Morocco’s abusive EU-funded refugee regime. You imagine that it must be a place of recovery as much as transit point.

Lecadet mentions that the migrants “use the term ‘ghetto’”[23] to describe the shelters they use. She mentions that this “recalls the ghettos of apartheid”[24] or “suburban areas of large American cities”[25]– Indeed, but what about the original ghettos of European Jews?

As with all communities, there are rules. In the Liberian ghetto, there is an enforced communism with a

obligation to “share their funds in order to pay for food and for the journeys of other members of the group through the desert”[26]. However, it is a authoritarian communism: “Obey, obey and obey”[27] is the watchword and a hierarchy with military ranks is adhered to.

In these descriptions, Lecadet avoids any easy sentimentalism, vividly portraying how both the positive and negative aspects of a culture are transferred and adapted to these micro-state(s) of limbo.

Taken together, these essays give a snapshot of deportation practices across both time and place. Volumes like this can be important because practitioners who work in the field barely have time to deal with what’s been thrown up by the latest bout of legislation, cuts and media scaremongering, let alone what happened in the past or in other countries coincides, or differs with what is happening in their immediate vicinity. This is a shame, as debates elsewhere or even in the past as this book clearly demonstrates have lessons for the present.

[1]pp134

[2]pp138

[3]pp13

[4]The Ottoman empire was in fact multifaith.

[5]pp115

[6] pp28

[7] pp41

[8]pp49

[9]http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/briefings/uk-public-opinion-toward-immigration-overall-attitudes-and-level-concern Viewed on 20/09/2013

[10]pp79

[12]pp98

[13]pp96

[14] Pp96

[15]pp81

[16]pp94

[17]pp94

[18]pp94

[19]pp95

[20]pp99

[21]pp99

[22]http://detentionaction.org.uk/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Detained-Lives-report.pdf Viewed on 21/09/2013

[23]pp146

[24] Pp146

[25] Pp146

[26]pp149

[27]pp149