workshop 2: the high seas of finance

If the world economy were an ocean, finance would be the currents and swells shifting resources from one shore to another. Sometimes the flows are steady, the surface looks millpond smooth … but then, out of the blue, things start to get rough …

Recap of workshop 1:

Capitalism is a complex system of many interdependent markets. For example, the car producer sells its products in the car market, and needs to buy inputs – raw materials, energy, labour – in lots of other markets. As a producer needs to buy inputs before making and selling its product, it often needs to get finance (i.e., borrow) from investors. Later, it will pay them back out of its profit … if it makes one.

Equity and debt.

Basically, companies can raise finance capital in two ways: by selling shares; or by borrowing. Markets trading shares are called equity markets. Markets trading loans and bonds, forms of borrowing, are called debt markets.

Nowadays things have got rather complex, and the distinction is not always so clear – but it is somewhere to start.

VOC trading ship.

VOC trading ship.

equity markets

Equity markets trade shares in the ownership of companies. Company Law sets out different ownership structures for companies:

– Most UK law or accountancy firms are partnerships. All the partners share responsibility for the company’s decisions. They share the profits; and also any losses and debts.

– A limited company is a special legal structure to limit the liabilities of the company’s owners. Shareholders have a share in any profits; but if the company goes bust, they are only liable for its debts and losses up to the value of their shares.

– A public limited company (PLC) or listed company is a limited company whose shares trade on an established stock market – e.g., the London or New York stock exchanges, the Paris Bourse. Anyone can buy and sell these companies’ shares through a stock broker. Only companies over a certain size can be listed, and they have to publish regular accounts.

Stock exchanges, where the shares of big PLCs are traded, are just the most visible face of the equity market. Many shares are traded in private deals between individuals and companies. Private Equity funds are investors who specialise in doing equity deals away from the listed markets.

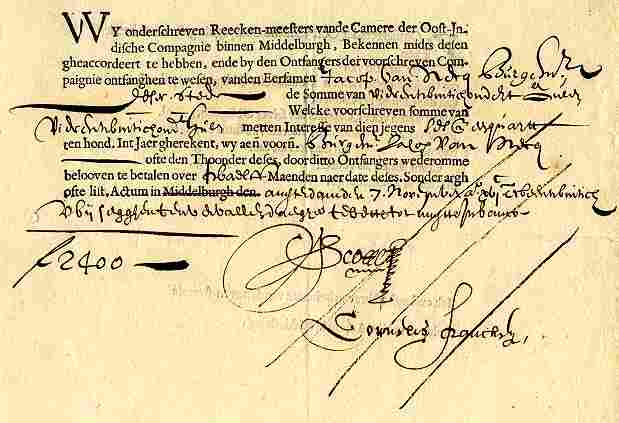

The first ever PLC was the Dutch East India Company (or: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC). Its shares were traded on the Amsterdam exchange from 1602.

VOC share certificate 1623.

VOC share certificate 1623.

The shareholders of a limited company are its legal owners. But a big corporation like BP has millions of shares, and many thousands of “owners”. Only shareholders who own a sizeable percentage of the shares have any real control over the company’s actions. Often, the managers or executives of the company, who are technically employees, have the real power.

Shareholders are entitled to a share in the profits of the company. Some of the company’s profits will be invested back in the business. What is left is distributed amongst shareholders: this payment is called a dividend. Big companies do not always pay out dividends, but shareholders can still make a profit by selling their shares – if the share price goes up.

……

Corporations.

The word corporation comes from the Latin corpus, a body. In Roman and medieval law, States recognised certain institutions or associations as legal persons – “bodies” with legal rights and responsibilities of their own, apart from their individual human members. For example, the Corporation of London, the governing body of the City of London, was granted its first royal charter in 1067. Many Lord Mayors and other individuals have been born and died since, but the corporation goes on with its own legal life and history.

Some say that the oldest business corporation was Sweden’s Stora Kopparberg mining corporation, chartered in 1347 and finally closed in 1992. Two important corporations in the capitalist history were the British and Dutch East India Companies (1600 and 1602), licensed by the British and Dutch states as monopolies to exploit the trade and colonisation of India.

Corporate law differs around the world, but everywhere it creates some form of legal separation between the corporation and the individuals who own and manage it. Corporations are usually Limited Liability Companies, which protects individual owners from responsibility for the company’s debts. But corporate law often goes further still, e.g., to protect individuals from criminal responsibility for the company’s actions.

……

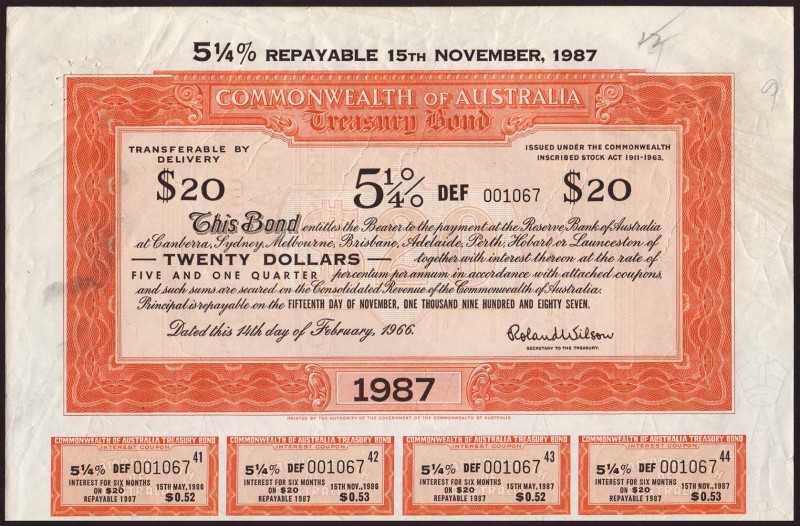

Australian treasury bond. Face value = $20. Fixed interest rate = 5.25%. Maturity = 21 years.

Australian treasury bond. Face value = $20. Fixed interest rate = 5.25%. Maturity = 21 years.

Debt markets.

There are two main ways in which companies can borrow money: getting loans from banks; or issuing bonds.

A corporate bank loan is basically the same as if an ordinary person gets a loan, only bigger. For very big loans, a number of banks may join together in a consortium (called a syndicated loan).

Any loan involves a contract. The borrower and the lender agree: the term of the loan, or when it has to be paid back (e.g., 3 months or 3 years); the interest rate (e.g., 5%, paid each year); any collateral which the borrower forfeits if doesn’t pay back the loan (e.g., in a mortgage loan, the collateral is your house). If the borrower doesn’t pay back the loan, this is called a default.

Banks make loans to companies, individuals, and governments. They also make loans to each other. One important financial market is the interbank loan market, where banks make short term (maybe only days) loans to each other. Banks use this market to balance their books if they are short of money in the short run. In financial crises, it may be one of the first markets to dry up if banks stop trusting each other.

A bond is to a loan what a publicly listed share is to private equity. Basically, a bond is a tradeable IOU, a loan contract that can be bought and sold by anybody in the bond markets. Originally, a bond was a piece of paper with something written on it like “I promise to pay you £100 on 1 January 2020”. When the date comes round, whoever owns the piece of paper can demand the money.

Bonds also have a term, or maturity date. Bonds are usually longer term than loans, often 10 or 20 years. And they have an interest rate, or coupon. Fixed rate bonds have a standard set coupon, e.g., 5% per year; variable rate bonds (like mortgages), have a coupon which moves with a reference interest rate (e.g., Libor – the London inter-bank lending rate – plus 2%).

A very brief history of banking and debt markets.

There are 4000 year old records of loans from Babylonian temples to merchants. Not only were money lenders based in temples, but the temple authorities often ran the business.

Modern banking is usually traced back to medieval italy – the word banca refers to the bench on which moneylenders would conduct business. The house of Medici opened in 1397. Italy’s Banca Monte Paschei dei Siena, founded 1472, is still going.

Medieval, like contemporary banks, could make money both from lending – to states, merchants, and the rich – and from taking deposits. Banks offered safe storage of gold, silver, and other valuables.

The basic idea is called deposit banking: savers deposit money in the bank; the bank can lend out the same money to borrowers, and charge interest. So long as too many savers don’t come to withdraw their money at once (a “bank run”), the bank can “cover” loans with deposits.

Early bank notes were simply receipts (“letters of credit”) for the metal coins a saver deposited in the bank. As banking networks spread across Europe, a merchant could use the same receipt to withdraw coins from different branches of a banking house, in Antwerp or Venice.

From the beginning, European debt markets were associated with the financing of war. Fortunes were made by the Venetian bankers who funded the crusades. The invention of bonds, or tradeable debt securities, goes back to the Dutch war of independence (from Spain) in the 16th century. The rebel Dutch state issued perhaps the first sovereign (i.e., government) bonds.

The Netherlands was the leading capitalist economy of the time. Other Dutch innovations included the foundation of the Bank of Amsterdam in 1609, possibly the world’s first central bank, guaranteed by the City government. The Bank of Amsterdam began to expand on the old deposit banking model by (secretly) issuing overdrafts: letting depositors take out bank notes (receipts) for more than they had deposited. The Dutch East India Company was the world’s first issuer of both listed shares and corporate bonds.

By the 18th century England had taken over the role of leading capitalist state. The Bank of England was established in 1694, copying the Amsterdam model. It was set up by Scottish merchant William Patterson in a deal with the government, which used it for military financing. The first loan, for £1.2 million at 8% per annum, funded the re-building of the Royal Navy.

England also led the way in advancing bond “technology”, issuing large standard issue “Treasury Bonds” that were widely traded in the coffee shops of London. From 1694 on the British state has been continually in debt, largely from war financing – its debt first rose over 100% of GDP in the 1750s, and stayed there for more than a 100 years.

The use of paper money took off in the 18th century. In 1844 the Bank of England was given an effective state monopoly (in London) on printing bank notes. Before then, any bank could issue as much “money” as it wanted – it was up to customers to decide if they trusted its reliability or not.

New Bank of England notes had to be backed 100% by reserves either of gold or of government bonds. I.e., the Bank had to keep the same value of either gold or Treasury bonds in its vaults to match the paper money it issued. The Bank became the “lender of last resort” to commercial banks: if they got into trouble, the central bank would lend them the money to cover any “bank run”.

Similar “gold standard” models were adopted around the world in the late 19th century. States either held their own gold and silver reserves, or pegged their currencies (fixed their exchange rate, and so limited the printing of new money) to Sterling or the US dollar. This system remained generally intact until the 1929 crash.

By the end of World War II the United States had clearly taken over from the UK as big capitalist power. The UK government was crippled by its war debts: 250% of GDP in 1945. In the Bretton Woods agreement of 1944, a new world monetary order was agreed which fixed most world currencies to the US Dollar. US Treasury Bonds became the ultimate “safe” asset against which risks and interest rates on all other debt was measured. And the World Bank and IMF, based in New York, were set up as “lenders of last resort” – and financial policemen – for the world economy.

In 1971, the US left the Bretton Woods agreement, unable any longer to support the world financial system, as its own debts — again, largely war debts, from Vietnam — massed up.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the US and other “advanced” capitalist countries followed neoliberal policies and “deregulated” their financial markets, allowing banks and brokers to develop whole new types of banking and financial markets involving derivatives and securitisation. As manufacturing industry increasingly switched to the “developing world” (see Workshop 3), the finance “industry” became the leading edge of capitalism in the US and UK.

……

“Fotia stis trapezes” = Fire to the banks.

A snapshot of world financial markets.

The table shows global assets: the amounts of the different kinds of securities in existence at that point. All figures in trillions of US dollars. Debt securities include bonds and short term notes – like bonds, but with maturities of a year or less. Private debt securities are bonds and notes from financial issuers (banks) and corporates.

| 1990 | 2000 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| Total assets | 48 | 112 | 194 | 178 |

| equities | 10 | 37 | 62 | 34 |

| private debt secs. | 10 | 24 | 48 | 51 |

| govt. debt secs. | 9 | 17 | 29 | 32 |

| bank deposits | 19 | 34 | 56 | 61 |

| World GDP | 21.2 | 37 | 56.8 | 60.7 |

World financial markets grew massively in the 1990s and 2000s, up until the crash. This was the neoliberal boom period of “financialisation”.

Both equity and debt markets shared in the boom. Government and private debt both boomed, but especially non-government debt. While markets in the early years mainly traded government debt, corporates – and especially banks and other financial institutions – are now big bond issuers.

Now to break down the figures geographically:

| Total financial assets ($ trillion) | 2007 | 2008 |

| US | 60.4 | 54.9 |

| Eurozone | 43.6 | 42 |

| Japan | 28.7 | 26.3 |

| China | 14.4 | 12 |

| UK | 8 | 8.6 |

| Latin America | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| “Emerging” Asia | 4.2 | 3.8 |

| Russia | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| India | 2.6 | 2 |

| Eastern Europe | 4.3 | 1.5 |

Sources: McKinsey Global Institute report

The most “developed” countries are far more “financialised”. China in fact produces around 22% of the world’s GDP – but less than 8% of financial assets are Chinese.

Meet the investors.

Who are these capitalists? Shareholders are, technically, the owners of companies and their capital. Bond investors and lenders (including bank depositors, who “lend” to banks) are the owners of “financial capital”, and get their share of the profits in the form of interest.

It is not so easy to get figures on capital ownership. The sums below are estimates by lobbying group “TheCityUK” of the size of global investment funds.

| $ Trillion | |

| Private wealth | 42.7 |

| Pension Funds | 29.9 |

| Mutual Funds | 24.7 |

| Insurance Companies | 24.6 |

| Sovereign Wealth Funds | 4.2 |

| Private Equity | 2.6 |

| Hedge Funds | 1.8 |

I have no idea how accurate those numbers are. Note that they don’t match up with the capital markets figures before – but then they miss out other major investors, which include banks and corporations. “Private wealth” means rich individuals and families, who do control a lot of the world’s capital. But “institutional investors”, put together, control more.

Institutional Investors manage the pensions, savings, and insurance premia of the world’s middle classes and better off workers. As with share ownership, we should distinguish legal ownership from actual control. Technically, these assets may be owned by individual savers; in practice, they are controlled by executives, fund managers. These companies decide where to invest the funds they manage, and take a percentage of the profits.

Some of these funds are bigger than large countries. Here are the top ten in the “Pensions & Investment” 500 (as of 2009). The amounts are their “assets under management” (AuM).

| $ tr | |

| BlackRock | 3.35 |

| State Street Global | 1.91 |

| Allianz Group | 1.86 |

| Fidlity Investments | 1.7 |

| Vanguard Group | 1.51 |

| AXA Group | 1.45 |

| BNP Paribas | 1.33 |

| Deutsche Bank | 1.26 |

| JP Morgan Chase | 1.25 |

| Capital Group | 1.18 |

Buy, sell … and in the middle.

In between borrowers and investors the two sides come a host of middlemen, including:

- Stockbrokers – middlemen who buy and sell shares for their investor clients

- Traders – who buy and sell bonds and other securities for clients

- Underwriters – bankers who buy bonds off a borrower when they are first issued, then sell them on to the market

- Insurers – e.g., offer insurance in case investments default

- Structurers – arrange complex securitisation bonds (see below)

- Derivatives dealers – see below

- Lawyers – lots of them

- Analysts – analyse securities to decide how risky they are, and what they should be worth

- … and more.

Arranging tricky financial deals is one of the riskiest, and best paid, parts of banking. The fees are usually a tight secret.

Traditionally, these roles were filled by brokers and specialist investment banks. In 1933, following the financial crash, the US State passed the “Glass-Steagal” act to regulate and keep investment banking divisions separated from deposit-based “commercial” banking. This law was repealed in 1999, and the same multinational banks now control both “commercial” and “investment” banking.

Risk and return.

The basic idea behind the price of a security: the riskier it is, the more profit it should pay.

Traditionally, US Treasury Bonds have been considered the ultimate “safe haven”. The assumption is that the US government will never go bust, and will always honour its debts. The coupon (interest rate) on US Treasuries is used a “benchmark” for pricing other debt.

The spread of a bond is the difference between it’s interest rate and the rate on another bond. For example, after the failure of the G20 meeting in November 2011, the spread on Italian over German 10 year bonds went to 459 basis points (4.59% – one basis point = 0.01%). I.e., markets demanded an extra 4.59% profit to buy Italian instead of German bonds.

(Note – slightly more technical: When a bond is first issued, it has a set interest rate, e.g., 4% per year, and is sold at a price of usually 100 cents per bond. Later, traders may decide the risk has increased. The interest rate will still be 4% of 100c = 4c; but now the bond will be sold on for just 80c. The yield, the profit that the new buyer will actually get from the bond, has gone up to 4c/80c = 5%. Higher risk, higher return. Italy’s yield in that example was 6.66%. Of course, if the bond actually defaults, the investor gets nothing.)

Rating agencies.

The infamous rating agencies – Moody’s, Standard & Poors, Fitch, and others – are companies that specialise in assessing the risk of debt securities. They publish a rating from AAA (the highest) down to D (default) depending on how likely they believe a bond is to default. They are paid on commission by the borrower issuing the bond. Obviously, they are completely impartial.

Many funds base their investment decisions on rating agency reports. Market prices are often guided by ratings. Also, pension and some other big funds are restricted by regulation to only investment grade bonds, bonds with ratings of BBB and over.

the new finance 1: securitisation

The great housing boom of the last 30 years was fuelled by a new kind of bond market. In the US, until the 1970s mortgage lending was largely done by small local lenders called the “Savings and Loans” or “Thrifts”, the equivalent of UK building societies. This sector was deregulated in 1980 and 1981, and later many of the “S&L”s were hit by crisis and went bankrupt.

Investment banks made this crisis into an opportunity. They bought up mortgages from the crashing S&Ls for cheap and moved into the mortgage industry. To help things along, the loans were guaranteed by US federal government agencies with cute names (Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae, etc.).

Unlike traditional mortgage lenders, investment banks didn’t have deposits which they could use to fund this business. Instead they invented a new technique called mortgage backed securitisation (MBS). They issued bonds secured against the expected repayments on the mortgages.

This relied on a legal structure called a “special purpose vehicle” (SPV). The mortgage borrowers pay their repayments into the SPV over, say, the next 20 years. A bond is issued in the name of the SPV, and the SPV pays out bond interest to investors. The interest paid out to the bond investors is less than the interest paid in by the mortgage borrowers. The investment bank sits in the middle and pockets the difference.

At first the new idea was strange to analysts and investors. But the federal government guarantees meant the bonds got a AAA rating anyway. Then the markets got used to the idea. Car loans and credit card loans were the next targets for securitisation.

“Shadow Banking”. Securitisation slashed away the old deposit banking model. Banks could lend out large sums to new hordes of customers, but without needing to get in any deposits. In the 90s and 2000s a new wave of “specialist finance companies” got in on the act, selling credit cards and mortgages from call centres, paper companies funded entirely by securitisation.

This consumer credit boom spread from the US through UK and Europe. By 2000 the gobal investment banks were arranging securitisation deals from Mexico to Kazakhstan. In the US, the new frontier was “sub-prime” mortgages: lent to people with dubious credit ratings; funded by bonds sold to investors hungry for higher returns.

the new finance 2: derivatives

The idea behind derivatives is actually rather old. The Greek philosopher Thales is said to have made a fortune on futures contracts. Predicting a great harvest, he placed orders with olive farmers for their whole autumn crop, agreeing a fixed price in advance. When the harvest came he got masses of olives cheap, and sold them on at a profit.

In general, a futures contract is an advance agreement to pay a set price for a good at a future date. When the future date comes around, if the market price for the good is higher, then the buyer of the futures contract makes a profit; if it is lower, then she loses the difference.

The first standardised futures exchange began in Chicago in 1865, where farmers and traders could agree futures contracts for wheat harvests.

Beyond agricultural futures, the derivatives market took off after the collapse of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange system in 1971. Fluctuations in international interest and exchange rates became crucial in financial deals. For example, a business seeking to invest in a foreign country might want to fix the exchange rate it would pay in the future.

On the one hand, derivatives offer a form of insurance. If I buy a futures contract to change money next year at today’s rate, then I ensure that I don’t have to pay more than the current price. On the other hand, I give up the chance to save money if the rate actually goes down over the next 12 months. This use of derivatives is called hedging.

On the other hand, derivatives can be seen as a form of gambling, or speculation. The other party in the currency futures contract may gamble that the rate will down, and so make them a profit.

Derivatives markets look even more like gambling if neither of the parties has any involvement in the actual good (wheat, currency) except the hope of a speculative gain. Two parties could make a contract just because they are betting different ways about what will happen to a reference asset – whether it’s an interest rate, a currency, or the weather.

An option is a contract that gives a party the choice to buy an asset at a set price in the future – or not to buy. Other types of derivatives include swaps, swaptions, and more.

The biggest class of derivatives contracts today are interest rate derivatives. These are used to hedge against the risk of losing out on investments which pay a return linked to a major interest rate.

As the securitisation market took off, investment bankers invented credit derivatives. Credit default swaps (CDS) and Credit Default Obligations (CDOs) are insurance contracts – or, seen another way, gambles – about whether debts will default or not. There is now a major market in CDS contracts on sovereign bonds.

CDS agreements also became routinely written in to mortgage securitisation deals, helping investors reduce their risk by hedging against defaults. A scandal broke, though, when it emerged that investment bank Goldman Sachs had used CDS deals to gamble that sub-prime bonds it had issued itself were going to explode – the financial markets equivalent of match fixing.

Complex CDO contracts involving bets on packages of mortgage and other debt became another way to expand the securitisation industry. They spread the “exposure” to risk on sub-prime mortgages and other debts to wider ranges of investors. CDO investors never actually had to buy any mortgages or bonds, just bet about what would happen to debts other people were buying. Investments in these deals are usually confidential, and the sums complex. Whole new levels of complexity were reached with “CDOs-squared”, and even “CDOs-cubed” – bets about bets about bets on debt defaults.

Just who else will be in trouble if a mortgage in Wisconsin defaults? Has anyone kept track?

….

further reading:

There are a few mainstream introductory books on global finance around. I haven’t checked them all out, but this one is okay: Stephen Valdez Introduction to Global Financial Markets

I think there is a lack of good “radical” studies of contemporary financial markets. Some of the stuff from the Dollars and Sense collective in the US is good, though generally quite US-focused.

But I usually find pro-capitalist finance sites more interesting and informative than the socialist ones. Here are a few worth checking out:

Nouriel Roubini, the “doctor doom” of the economics profession, and his gang of researchers: http://www.roubini.com/

Paul Krugman, the guru of liberal economists, has a blog at the New York Times: http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/

If you want to do more research yourself on the intricacies of financial markets, there are various places to look for reports, statistics, etc. Often the most interesting are research reports by the investment banks themselves. Some of these you can find by googling about, though many are restricted access. If you are really inquisitive, one thing you could do is call up the banks’ press offices and ask for their research on a particular topic saying you are a freelance journalist. Otherwise, a few other sources of info:

International organisations and industry bodies:

IMF: publish annual “global financial stability report”, “economic indicators”, and other interesting stuff: http://www.imf.org/external/pubind.htm

World Bank: also lots of data and research publications, mostly public access: http://econ.worldbank.org/

ISDA (International Swaps and Derivatives Association), the international industry body / lobbying group for derivatives issuers and traders. Publishes research papers, anti-regulation propaganda, statistics and other info: http://www2.isda.org/

If you are interested in specific countries or regions, look at local central bank and finance ministry websites, and local industry bodies.

Ratings agencies:

Those evil agencies publish both their “rating reports” on transactions, and the underlying methodologies behind them, as well as more general research papers. These are a really important source of info on securitisation deals and such. Some are freely available, though you may have to fill out a registration form.

Fitch: Fitchratings.com

Moodys: http://www.moodys.com/

Standard & Poors: http://www.standardandpoors.com/