A brief history of capitalist desire

“It’s a power plant that runs its turbines on a gigantic reservoir of unwept tears, always on the verge of spilling over.” The Invisible Committee.

In many parts of the world, capitalism now seems unchallenged as the dominant culture. It hasn’t always been like this. For most of its history, capitalism struggled to survive, and to spread and grow. Looking back, it’s remarkable how devastatingly successful it has been. No other culture has transformed the world so dramatically in just a few hundred years. Capitalism is on a roll. Which doesn’t mean it’s unstoppable.

How has capitalism been so successful? Here are just a few points to look at:

** Invasive culture. Capitalism is, to the core, an invasive culture. The ‘passion of self-interest’ may not be the eternal core of human nature, but it has proved a powerful motor. It drives the entrepreneurs and colonisers at the frontline of capitalism on a continuing crusade for new markets, new commodities, new sources of profit and exploitation.

** By force. To expand, capitalism has to confront and overcome other cultures. It can do this in different ways. One way is by physically, and psychologically, smashing them with violence. Here it can draw on a massive power to produce and organise industrial and military resources.

** By contagion. Another way is to spread its own ways of life contagiously, infecting other groups with its values and desires. Often these two techniques go together: first, the use of force to destroy existing ways of life, traumatise individuals and their values; then, spreading new desires to weakened bodies.

** By assimilation. Where capitalism faces strong opposition, it can also work by adapting to, and eventually assimilating,or perhaps merging with, rival cultures. For much of its history, capitalism lived in an uneasy relationship with feudal and aristocratic elites, before eventually largely assimilating them within its new forms of life. In the 20th century, capitalist elites learnt to adapt to, accommodate, and assimilate workers’ and socialist movements.

** Crises. Capitalism does have deep instabilities. It is riven by internal competition, conflicts and collective action problems. For example, capitalism seems completely incapable of organising any concerted effort to stop destroying the natural world it sucks dry. But as a machine of destruction it is unparalleled, and it keeps on surviving through every crisis.

** Re-invention. Key to its survival is its ability to constantly transform and reinvent itself. In the nineteenth century, Marx predicted that capitalist economies would stop growing as they ran out of technologies and markets to exploit. Yet capitalism has kept on creating new technologies and markets, in completely unpredictable ways. We’d be foolish to hope that capitalism will destroy itself through any ‘internal contradictions’.

We want to look at some of these themes now in a whistle-stop tour of capitalist cultural change in the ‘developed world’ in the last 500 years. This is necessarily very incomplete: and, in particular, it is much too focused on the well-written history of Europe, and above all England. But it’s kind of a start.

……

1) The rise of the bourgeoisie

Maybe there have always been a few individuals dedicating their lives to getting rich. In medieval Europe, the ancestors of today’s capitalist billionaires were powerful families of bankers and merchants like the Medicis and the Fuggers, who created mini-empires based on international trade and financing the sristocrats’ crusades and wars. The protestant Dutch republic, declared in 1581, is sometimes seen as the first capitalist state. Its wealth came from new international trade routes with the American colonies and the Far East, as well as a concentration of skilled craftspeople and merchants, including many protestants fleeing from religious persecution elsewhere in Europe. Writers at the time were fascinated with what seemed like a new culture being created in the low countries, in which the merchant class wielded considerable political power with relative independence from the old feudal lords.

But the real breakthrough for capitalism came in England. A lot of historians have written about the rise of the English bourgeoisie in the 17th and 18th centuries. Here are a few oft-mentioned points:

** The spread of non-conformist protestant sects, especially Calvinism and later forms of puritanism, which valued hard work, saving, and accumulation of wealth as moral virtues. This thesis is famously explored by Max Weber in his The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

** The reformation and dissolution of the monasteries, under Henry VIII, transferred massive wealth from the old religious orders to ‘nouveaux riches’ individuals. This also meant a leap in the enclosure of common lands, as the new landlords broke traditional arrangements between the monasteries and peasant villagers. R.H. Tawney emphasised the importance of this event, and its place in a general shift in English religious and class politics.

** In general, the 17th and 18th centuries saw the emergence of a new ‘class conscious’ bourgeoisie, with both great wealth its own thriving culture. The ruling classes became increasingly dependent on middle class funds to wage colonial wars and maintain its lifestyle. Middle class leaders used their financial power to make successful alliances with ‘respectable’ working class radicals on the one hand, and modernising ‘Whig’ aristocrats on the other. They were able to gain increasing political power, from the Civil War (1642-51) and the ‘Glorious Revolution’ (1688) coup against Catholic King James II, through to the 19th century Reform Acts. This political power was used to transform property laws, deregulate markets, and attack workers’ traditional rights.

** Early forms of capitalism were based on finance and trade, rather than the direct exploitation of labour. Two major new kinds of production changed all this, and massively built up the wealth and power of capitalist entrepreneurs further. In the colonies, slave plantations produced bulk consumer goods such as sugar and coffee, and raw materials such as cotton. Back home in Europe, with the industrial revolution, the factory system concentrated hundreds of workers paid near-starvation wages to produce textiles and other valuable commodities.

……

2) Making slaves and workers

Many histories focus on the cultural changes needed to create a strong new capitalist class and culture. But industrial capitalism also involved the creation of other radically new forms of life. Millions of people in Asia, America and Africa were slaughtered, invaded, colonised and enslaved. Millions of Africans were ripped from their homelands, had their traditional cultures destroyed and repressed, to be turned into plantation slaves. Millions of Europeans were dispossessed from their lands and villages to be turned into workers.

As well as murder and destruction, these ruptures meant the creation of new groupings and cultures. Mestizo cultures of the Americas; Atlantic cultures of black slaves, and maroon cultures of escaped fugitives; proletarian cultures of European factory workers; cultures of settlers and migrant workers moving across states and oceans; and many more.

In early European capitalism, a pressing issue was the threat posed by the many villagers dispossessed by land enclosures. The English elites lived in perpetual terror of hordes of ‘vagabonds’ and ‘paupers’ lawlessly roaming the countryside, and forming unruly mobs in the city slums. From the 16th century increasingly harsh punishments and controls were brought in to settle the ‘itinerant’ population, from Tudor hangings and ear-cuttings to the more efficient Victorian workhouse system. The ideal long-run solution was offered by the factories, machines for turning vagabonds into proles. But this wasn’t any easy process: proletarians need to be trained and disciplined into labour. Marx put it like this:

‘Thus was the agricultural people, first forcibly expropriated from the soil, driven from their homes, turned into vagabonds, and then whipped, branded, tortured by laws grotesquely terrible, into the discipline necessary for the wage system. […] The advance of capitalist production develops a working class, which by education, tradition, habit, looks upon the conditions of that mode of production as self-evident laws of nature.’ (Capital Volume 1: Chapter 28).

Marx’s historical insight here is powerful. But note how he sees the proles as just passive victims in this process. More recent writers, including Marxist historians like E.P. Thompson, have studied the active role played by workers in the ‘making of the working class’. Violence and control from ‘above’ was certainly crucial; but slaves and workers have their own ideas about how to respond to attacks, their own strategies and tactics of accommodation or resistance. By dispossessing people and destroying their existing ways of life, capitalism forced the creation of new cultures of slaves and workers. But it could not entirely control just how these new cultures developed.

Indeed, throughout the history of capitalism, movement and migration has nourished revolutionary cultures. To give just a few examples: English itinerants in the 17th century spread radical religious ideas such of those of the Levellers, Diggers and Ranters; as similar vagabonds had done in the Germany of the peasants wars a century before. In Spain and Italy in the 19th and early 20th centuries, anarchism was carried from village to village, or between cities, by landless and migrating labourers. In Argentina, ‘crotos’ or anarchist tramps played a similar part as they moved from farm to farm; as did ‘Wobbly’ syndicalist migrant workers in the western United States. Whilst trans-Atlantic migrations spread European anarchist movements to New York, Chicago, Buenos Aires or Sao Paulo.

In these situations the breakdown of traditional and local identities didn’t mean a passive mass waiting to be enslaved. It was the birth of new possibilities and cultures that posed a deadly threat to capitalism.

……

3) Building the nation

The growth of capitalism goes together with the rise of the nation state. In Europe, rulers created new national infrastructure to support the growing markets, such as:

-

Transport: railways and canals, to move commodities.

-

Ports: for international trade, defended and policed by customs systems and navies.

-

Armies and police forces: to enforce property law.

-

Parliaments: where capitalists and industrialists shared power with the old aristocratic elites.

Alongside enclosure and the growth of industrial cities, transport and national markets were further forces that dispersed local communities and put people on the move. But they also brought capitalists a crucial new weapon: nationalism. From the late 18th century on, as bourgeois groups began to gain political power, they used it to build new kinds of state institutions that were all about creating national identities. These included:

** Patriotic wars and conscripted national armies, which really took off with the French revolutionary and then Napoleonic wars.

** State-sponsored education systems: teaching conformity, patriotism, and the “naturalness” of the market system.

** National mass media, controlled by capitalist media barons.

** From the end of the 19th century, national insurance and welfare systems.

Wherever resistance to capitalism was on the rise, nationalism was a key response. Every time workers’ movements started to threaten the elites, rulers mobilised patriotic feelings against “foreigners” or “unpatriotic” radicals. Just to take a few examples from English history:

-

1780s+: Patriotic “Church and King mobs”, paid mainly in beer by crown agents, were used to attack and intimidate “Painites” and “Republicans”.

-

1800s: Napoleonic wars. Repression against trade union and radical organisers justified by war conditions, radicals accused of being French spies.

-

1890s: Introduction of “Aliens Act”, first major anti-immigration legislation, in a climate of media hysteria against Jewish “anarchists” and other undesirables.

-

1914+: First World War. Internment of foreigners, censorship and martial law. Patriotic upsurge (across Europe) helps dampen dangerous syndicalist movements.

-

1982: Falklands War. A new war, a new patriotic frenzy, helps the neoliberal Thatcher government back to power in the 1983 elections, despite recession and massive unpopularity before the conflict.

-

2000s: UK becomes world’s most surveilled state, as government whips up and rides panic over Muslim “terrorism”.

4) Mass production and consumerism

But by the beginning of the 20th century capitalists in the most “advanced” industrial nations faced two very big problems.

-

Revolutionary movements. More “enlightened” elites used concessions such as workplace reforms, wage increases, and charity, alongside nationalism, to calm workers. But many people still saw capitalism as their enemy, and resistance was growing.

-

Lack of consumers. As production kept on growing, producers were running out of affluent customers to sell to.

Mass consumerism saved the day for capitalism, and transformed the world. The change is often dated back to 1910, when Henry Ford set up the first “production line” in the Highland Park, Michigan car plant. On the original 1910 production line it took workers 12 hours and 48 minutes to assemble one car chassis. By 1914 Ford had got it down to one hour and 33 minutes, and the Highland Park factory produced over 1000 cars a day. Over the next 10 years “Fordist” methods were copied across American industries, as every producer raced to keep up. (This section draws on Stuart Ewen’s book “Captains of Consciousness”.)

But now the new factories were producing much more than the small upper and middle classes could buy. More intelligent capitalists could see what would have to give. The market had to be expanded, and the only way to do that was to welcome the workers into consumer society. US President Herbert Hoover made it clear in this speech in 1926:

“The very essence of great production is high wages and low prices, because it depends on a widening range of consumption only to be obtained from the increased purchasing power of high real wages and increasing standards of living.”

The problem is that someone has to go first: if one boss raises wages, but her competitors don’t, then she is at a competitive disadvantage. (Another classic “collective action problem” — see Chapter 5). This was Marx’s argument for why wages will always be forced down to subsistence level, and capitalism be condemned to crises due to lack of consumer demand.

Yet in the 1920s advanced capitalist economies did manage to solve some of their collective action problem, raise wages and living standards, and cut working hours. Ford himself led the way with the famous five dollar work-day wage in 1914. But still wages didn’t rise nearly as fast as production, and the gap in consumer demand was largely filled by credit (mainly instalment plans), which indeed contributed to the financial boom and then the massive bust of 1928. It was really after World War 2 that workers’ living standards in the industrialised world increased rapidly, thanks to Keynesian government intervention.

Manufacturing demand

However, it turned out that just paying workers more, and giving them time to spend their wages, still wasn’t enough. Workers might decide to save their income instead of spend it, remembering the hard times that weren’t so far away. Or, rather than endlessly pursuing the lust of avarice, they might have other things to do with their “free time”.

This is where advertising came in. Before mass production, advertising had been about highlighting special qualities of a product to make it stand out from similar commodities. The new breed of advertising gurus in a rapidly growing industry saw this as too primitive. The idea now was to create a “real or fancied need” for the product in the first place. Schooled in the latest Freudian psychological theories, advertisers sought to create new desires by appealing to “profound .. human instincts”. In particular, they targeted the “instinct” for “social esteem”.

The main technique was to create feelings of “social insecurity” which their products were supposed to ease, albeit temporarily. How can you find a husband if your nails aren’t fashionably polished? How will you get ahead at the office if you had bad breath from not gargling with listerine? If immigrants wanted to be accepted they needed to dress like proper Americans. Be anxious about your body, your background, your neighbours, your workmates, the modern world is a rat race and you need to stay sharp to keep afloat. A 1938 article in the ad industry journal Printer’s Ink put it bluntly:

“advertising helps to keep the masses dissatisfied with their mode of life, discontented with ugly things around them. Satisfied customers are not as profitable as discontented ones.” (quoted in Ewen p38)

This dissatisfaction is not one that calls for political or collective solutions. The solutions are individual, products you can buy. But there are always more problems to come, more lacks and failings, more commodities you need to buy to keep up with the others. Cultivating the “instinct for social esteem”, mass consumerism became an endless race on a treadmill, an itch you can’t ever scratch.

……

5) “Recuperation” and resistance.

The 1960s saw an outbreak of anti-consumerist rebellions amongst students and youth, mainly in rich countries. Counter cultures which rejected establishment values and desires spread with unexpected speed. Suddenly everyone took LSD and had group sex in parks, and some even took part in student occupations and new revolutionary movements.

One new intellectual current of the 1960s was the Situationist International radical/art movement. According to the SI writer Guy Debord, society in advanced capitalist countries had become a “spectacle”. Commodification had “completed its colonisation of social life”. In the “society of the spectacle”, the only meaning left in our lives comes from the things we “have”, or try to have; all our desires are shaped by the “images” we passively receive from advertising billboards and TV screens, and see reflected back off the other consumers we try to keep up with.

If everything is produced for us by an immensely powerful capitalist system, what can we ever do to escape being just passive consumers? The SI’s answer was what they called (in French) “detournment” (there isn’t any great English translation – maybe “re-turning”, “derailing”, or just subversion). This means: we take the products and values fed to us by the system, but instead of consuming them passively, change them, mix them up, hack them, pervert them. Here the SI gave a theoretical name to what youth subcultures have always been doing. From the English “Teddy Boys” in the 1950s adopting aristocratic Edwardian fashion and turned it into working class machismo; to punks and queers taking derogatory labels and images and turning them into symbols of defiance.

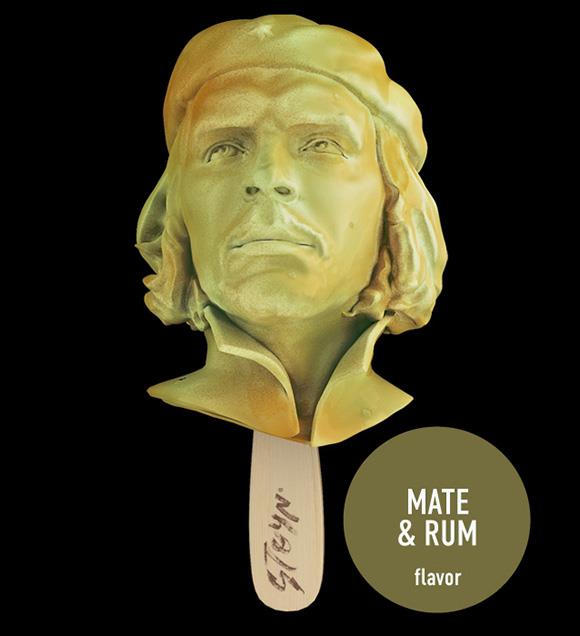

But the flipside of subversion is what the SI called “recuperation”. This means: the establishment takes a “radical” symbol or value and makes it safe, acceptable, and marketable. A classic example is the face of Che Guevara on a million T-shirts. In the 1970s, a new wave of advertising execs found that they could make just as good money selling new “alternative” commodities to the youth. Was the lasting legacy of 60s counter-culture just some new lines in consumer products?

Our desires don’t appear from nowhere. They are embedded in the ways we live, in our interactions and relationships, in our habits and practices, in the value systems and power systems we live in. As advertising execs know, creating desires is fundamentally about creating identities. You desire the car, the watch, the shoes because of who they make you: successful businesswoman, playboy, filmstar, upstanding citizen, loving husband, wife and mother. Or: gangster, bad girl, rebel.

Capitalism offers a repertoire of roles or identities to aspire to. Each one is a dream of how you can live, what you can be. Simplifying, we might identify some historical stages of capitalist dream creation:

-

In the early days (18th and 19th centuries), the identities you could aspire to were very limited by obvious social hierarchies. As wages were pushed low and people could only afford necessities, workers were not of much interest as consumers. Elites mainly tried to shape workers’ identities and desires through the state (nationalism, schooling) and religion. But their grip on people’s desires remained fairly weak. Anti-capitalist movements had the space to thrive, and they offered people different desires, identities, and dreams. These alternatives were a real threat to the elites. Lacking “consent”, the state had to routinely use extreme force to defend property and markets.

-

In the 20th century, mass production and mass consumerism created new identities for workers in rich countries. Now many more people could be included in the capitalist dream. But the available identities were uniform. Advertisers worked on the same lines as state education, promoting a basic set of roles: heterosexual nuclear family roles (husband and father, wife and mother); successful careerist; responsible citizen; patriot.

-

Responding to 1960s counter-culture, advertisers started to offer a wider range of identities. Even identities that go against state-promoted norms can be profitable. With less uniformity, there can be more tension between different corporate and state-promoted values — but they usually manage to get along in the end.

Old or new, conformist or “rebel”, profitable consumer identities all need to share some basic properties.

-

The role needs to be defined by commodities, by what you have.

-

You have to remain dissatisfied and anxious in the role. You can never be quite sure that you’re doing it right, there’s always a risk of losing your place. Very often, this dissatisfaction is linked to anxiety about status — about your position relative to other consumers. But in any case, the essential result is: you always need more.

……

……

6) The creed of growth

Economists, politicians, journalists, and anyone else on TV, Left-wing or Right-wing, agree on one big thing: the goal is growth. Growth means producing and consuming more stuff. If the economy falls into recession everything goes wrong. People lose jobs, people go hungry, hospitals close, and your granny has to sleep on the street.

By the early 20th century, most of the “Left” had accepted mass industrial production and consumption, but insisted that wealth should be spread more equally. Whether by revolution or income tax, there should be redistribution of wealth away from the rich to the poor.

One of neoliberalism’s victories is the idea that everyone can get richer together: the needs of the poor don’t have to be satisfied by taking from the rich. If we can create enough stuff, at least some of it will “trickle down” to those at the bottom. The rich get richer, and the poor get richer too.

In the richest nations, until very recently, this idea actually seemed to work. Living standards, or the amount of stuff you have, were going up for almost everyone. Certainly, the rich were doing the best of all, getting most of the new stuff – and so inequality has risen dramatically. But there was still enough new wealth left to improve incomes at the bottom.

By the start of the 21st century, these once weird ideas have become mainstream ‘common sense’:

-

Everyone wants more and more stuff.

-

The economy can keep on creating more stuff for everyone.

-

To keep it going we need to let markets be “free”: regulation or redistribution would hurt the markets, and the engine of growth will stop.

-

To keep it going, we all need to keep wanting more stuff.

Even in very narrow economic terms, there are a few problems here, and recent crises should be making these increasingly apparent. For example:

-

As we saw in Chapter 5, most people in rich countries were only getting more stuff because they were getting heavily into debt.

-

As we saw in Chapter 3, rich economies as a whole only carried on getting more stuff because they were getting heavily into debt to productive ‘developing’ countries.

-

The world as a whole does still keep producing more stuff. But for how long? This growth has been made possible by cheap petroleum, massive quantities of easily extractable fuel. Cheap fuel is disappearing. And now the ecological cost of industrial growth is starting to hit us.

And zooming out from the restrictive frame of capitalist culture: is more and more stuff really what we want? Is it giving us what they said it would? Is it what we really want to want?

……

“Brothers and Sisters, what are your real desires? Sit in the drugstore, look distant, empty, bored, drinking some tasteless coffee? Or perhaps BLOW IT UP OR BURN IT DOWN. The only thing you can do with modern slave-houses — called boutiques — IS WRECK THEM. You can’t reform profit capitalism and inhumanity. Just kick it till it breaks.”

The Angry Brigade — Communique 8.

……

Reading suggestions:

For Weber, Tawney, Marx and all, see the references above to Chapter 1.

On the dispossession and ‘disciplining’ of the proletariat, again, Silvia Federici – Caliban and the Witch.

On the history of advertising and mass consumerism, Stuart Ewen is excellent. The section here largely follows his Captains of Consciousness. His more recent book PR! A Social History of Spinis also good.

Another useful history of US advertising and consumer culture is William Leach – Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture.

Adam Curtis’ TV documentary series The Century of the Selfalso largely follows Ewen’s account, with an added emphasis on the link between advertising and Freudianism. Some of the claims are a bit simplistic, but it is fascinating and entertaining. Last time we looked it was all up on youtube.

Guy Debord’s master work is The Society of the Spectacle. There’s also a movie version, which should be on youtube. The other SI classic is Raoul Vaneigem – The Revolution of Everyday Life. Both these, and more, are available at this SI online library: http://www.nothingness.org/SI/

On subcultures, and subcultural resistance, see (again) Dick Hebdige – Subculture: the Meaning of Style.

The first part of The Coming Insurrection(by the “Invisible Committee”) is certainly influenced by Debord in its style as well as content. The second part, which moves from critique to theses for new insurrectionary movements, is also worth reading.

But if you really want French theories of desire, nothing compares to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari – Anti-Oedipus.