Some books, pamphlets, articles and other texts, which we have selected because they give accounts of resistance to World War One, the causes of the war, its effects, the initial collapse of the left and radical movements in the face of its outbreak, and related issues. Obviously this is just a beginning of a comprehensive list; any other titles, links, suggestions, welcome – email us at: therealww1@riseup.net.

Thanks to the Real WW1 blog and Remembering the real WW1 list for this excellent resource.

General accounts:

• Adam Hochschild, To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-18

• Avner Offer, The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation

• B. Tuchman,

The Guns of August

• http://www.libcom.org/history/peoples-history-world-war-i-howard-zinn

An extract from Zinn’s ‘A people’s history of the United States’, relating the US’s participation in WW1 and resistance to it.

• John Zerzan, Origins and Meaning of WWI, Telos, no. 49, Fall 1981. (http://www.scribd.com/doc/49337748/Zerzan-Origins-and-Meaning-of-WWI)

• John Morrow, The Great War: an Imperial History.

Preludes to World War 1: The Balkan Wars

• The War Correspondence of Leon Trotsky: The Balkan Wars 1912-13

Preludes to World War 1: (part ii): The pre-war Syndicalist Revolt and the upsurge of class struggle.

• David D. Roberts, The Syndicalist Tradition and Italian Fascism (1979)

• SelfEd Collective, Revolutionary Syndicalism in Britain and Ireland, 1910-17.

http://www.solfed.org.uk/cache/normal/www.selfed.org.uk/a-s-history/unit-6-revolutionary-syndicalism-in-britain-and-ireland-1910-17_.html

The Causes of the War

• V I Lenin

, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. (1916)

http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/

• Woodruff D. Smith, European imperialism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries.

• Edward E. McCullough, How The First World War Began.

The Left and the outbreak of War

• Merle Fainsod, International Socialism and the World War (1935)

• Georges Haupt, Socialism and the Great War: The Collapse of the Second International. (1972)

• Vladimir Lenin and John Riddell, Lenin’s Struggle for a Revolutionary International

, Monad Press, 1984 ,

The debate among socialist leaders, including V.I. Lenin and Leon Trotsky, on a socialist response to World War I.

• V.I. Lenin, The Collapse of the Second International.

• V.I. Lenin, Imperialism and the Split in Socialism

• Lenin/Zinoviev, Against the Stream.

• Rosa Luxemburg, On The Spartacus Program (1918)

http://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1918/12/30.htm

• Rosa Luxemburg, The War and the Workers – The Junius Pamphlet (1916)

http://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1915/junius/index.htm

• George Novack, Dave Frankel & Fred Feldman, The First Three Internationals, Their History and Lessons

• John Quail, The Slow Burning Fuse: The Lost History of British Anarchism.

Contains chapters on the wildly varying positions of British anarchists on the outbreak of the War.

• Leon Trotsky, Political Profiles (1972)

Contains profiles of leading socialists in the pre-WW1 period, and their actions around the outbreak of the War.

Mutinies and solder’s strikes

• P. Adam-Smith, The Anzacs: The True Story of the Young Men Who Went to Gallipoli, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne 1978, a nostalgic nationalist perspective, includes brief account of September 1918 mutiny by ANZAC troops.

• William Allison and John Fairley, The Monocled Mutineer, Quartet Books, London 1978, an overblown account of the 1917 Etaples Mutiny and biography of a rapist, thief and murderer.

• William Allison, Inadmissible Memories of a Suppressed Mutiny, Guardian, 22 September 1986.

• Anthony Babington, The Devil to Pay: The Mutiny of the Connaught Rangers, India, July 1921, Leo Cooper, London 1991, a comprehensive account of the mutiny in 1920 of the Connaught Rangers at Jullunder in the Punjab on hearing of the execution of the leaders of the 1916 Easter Uprising, but generally unsympathetic to the mutineers.

• D. Birmingham, et al. (eds.), World War 1 and Africa, Journal of African History, Volume 21, no. 1, 1978, scholarly essays, some referring to mutinous action by African soldiers and military labourers.

• N. Boyack, Behind the Lines: The Lives of New Zealand Soldiers in the First World War, Allen and Unwin, Wellington 1989, a critical account of NZ troops, includes references to mutinies and ill-discipline, fully referenced.

• R. Boyes, In Glass Houses: A History of the Military Provost Staff Corps, Military Provost Staff Corps Association, Colchester 1988, ill-written, poorly edited and over-defensive, but useful for references to revolts by military prisoners.

• S. Brugger, Australians and Egypt 1914–1919, Melbourne University Press, Carlton 1980, includes references to ‘Wazza’ pogroms, good bibliography.

• R. Ducoulombier, Une nouvelle histoire des mutineries de 1917

• David Englander, Mutiny at Etaples Base Camp, The Bulletin for the Society of Labour History, no. 52, 1987.

• John Field, The Kent Coast Mutinies of 1919, Cantium, Volume 4, no. 4, Winter 1972–73.

• J.G. Fuller, Troop Morale and Popular Culture in the British and Dominion Armies 1914–1918, OUP, Oxford, 1991, concerns sport and leisure, refers to officers, ill-merited self-esteem, mutinies viewed as insignificant.

• B. Gammage, The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War, ANUP, Canberra 1974, refers to the 1915 anti-Egyptian pogroms and September 1918 mutinies.

• D. Gill and Julian Putkowski, The British Base Camp at Etaples 1914–1918, Musée Quentovic, Etaples sur Mer, 1997, includes a brief account of the 1917 mutiny, dismisses the ‘Monocled Mutineer’ thesis.

• Douglas Gill and Gloden Dallas, Mutiny at Etaples, Past and Present, no. 69, November 1975.

• Douglas Gill and Gloden Dallas, The Unkown Army: mutinies in the British army in World War One. (London, 1985.)

• F. Grundlingh, Fighting Their Own War: South African Blacks and the First World War, Ravan Press, Johannesburg 1987, makes reference to mutinies by the black military labourers of the South African Labour Contingent.

• R.W.E. Harper and H. Miller, Singapore Mutiny, OUP, Singapore 1984, recounts February 1915 mutiny by sepoys of Fifth Battalion Light Infantry, but generally discounts the political significance of the outbreak.

• L.F. Guttridge , Mutiny: A history of Naval Insurrection (Ian Allan 1992)

• L. James, Mutiny: In the British and Commonwealth Forces 1797–1956, Buchan and Enright, London 1987, mostly about post-1914 period, many useful references but a whiggish interpretation of mutiny.

• T.P. Kilfeather, The Connaught Rangers, Anvil, Dublin 1969, a journalist presents a sympathetic account of 1921 protest, no references or bibliography.

• A. Killick, Mutiny!, Spark, Brighton 1968, reprinted 1976 by Militant, an autobiographical account by a participant in the 1919 Calais mutiny.

• Dave Lamb, Mutinies: 1917-1920. (Solidarity pamphlet, 1977).

Online at http://www.libcom.org/library/mutinies-dave-lamb-solidarity

• S.P. Mackenzie, Politics and Military Morale: Current Affairs and Citizenship Education in the British Army 1914–1950, OUP, Oxford 1992, references to Etaples 1917, April 1918 Soldiers’ and Workers’ Council, and Cairo 1944.

• Edt. C.L. Mantle, The Apathetic and the Defiant: Case studies of Canadian Mutiny and Disobedience, 1812-1919 (Dundurn Group and Canadian Defence Academy 2007)

• D. Morton, Kicking and Complaining, Canadian Historical Review, no. 61, September 1980. (Kinmel Mutiny)

• D. Omissi, The Sepoy and the Raj: The Indian Army 1860–1940, Macmillan, London 1994, devotes a chapter to mutinies by the sepoys of the Army of India, good bibliography.

• Guy Pedroncini, Les Mutineries de 1917, Presses universitaires de France, 1967 ; 4e édition corrigée 1999 (ISBN 978-2130473756) and –

• Guy Pedroncini, 1917, les mutineries de l’armée française, Julliard, 1968.

• R.J. Popplewell, Intelligence and Imperial Defence: British Intelligence and the Defence of India 1904–1924, Cass, London, 1995, refers to ‘Ghadr’-inspired mutinies in Army of India during 1914–15, excellent references.

• S. Pollock, Mutiny for the Cause, Leo Cooper, London 1969. A journalistic hagiography of the 1920 Connaught Rangers mutiny.

• C. Pugsley, Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story, Hodder and Stoughton, Auckland 1984, describes the ‘Battle of Wazzir’, an anti-Egyptian pogrom due to NZ troops’ ‘pent-up frustration’, see also Boyack.

• C. Pugsley, On the Fringe of Hell: New Zealanders and Military Discipline in the First World War, Hodder and Stoughton, Auckland 1991, nostalgic nationalism, refers to several mutinies, including December 1918 Surafend anti-Arab pogrom (‘cannot be condoned but can be understood’), contrast with Boyack.

• Julian Putkowski, British Army Mutineers 1914-1922, (November 1998) Francis Boutle Publishers, 0953238822, ISBN 9780953238828

• Julian Putkowski (1989), The Kinmel Park Camp Riots, Flintshire Historical Society, 0951277618, ISBN: 0951277618

• Julian Putkowski, Mutiny in India, 1919. http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/revhist/backiss/vol8/no2/putkowski2.html

• Al Richardson (Ed.), Mutiny: Disaffection and Unrest in the Armed Forces. Revolutionary History, Volume 8, no 2 (2002). A collection of articles on (mostly British) army mutinies, including several around World War 1.

• Andrew Rothstein, The Soldiers’ Strikes of 1919. (London, 1980.)

• T.R. Sareen, Secret Documents on the Singapore Mutiny, 1915, two volumes, Mounto, New Delhi, 1995, includes Court of Enquiry papers and other items associated with the outbreak.

• G. Sheffield, The Redcaps: A History of the Military Police and its Antecedents from the Middle Ages to the Gulf War, Brassey’s, London 1994, an official history, only Etaples 1917 outbreak cited, but useful references to battlefield ‘stragglers’.

• G. Sheffield, Leadership in the Trenches: Officer–Man Relations, Morale and Discipline in the British Army in the Era of the First World War, Macmillan, London 2000, refers to several mutinies but eschews ideology and opts to maintain a ‘Soldiers’ deference + Officers’ paternalism = good officer–man relations’ line, excellent bibliography.

• P. Stanley, Bad Characters: Sex, Crime, Mutiny, Murder and the Australian Imperial Force. (Pier 9 2010)

• M. Summerskill, China on the Western Front: Britain’s Chinese Workforce in the First World War, Summerskill, London 1982, includes references to mutinies by Chinese Labour Corps serving with the British Expeditionary Force.

• Peter Tatchell, The Monocle That Blinds Us to the Many Other Mutinies, Guardian, 19 September 1986.

• The Murmansk Mutiny

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/making_history/making_history_20080408.shtml

• Steve Johns, The British West Indies Regiment Mutiny, 1918.

http://libcom.org/history/british-west-indies-regiment-mutiny-1918

Resistance, desertion and soldiers’ daily experience

• A.E. Ashworth, The Sociology of Trench Warfare 1914-18, British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 19, No. 4 (Dec., 1968), pp. 407-423

• A.E. Ashworth, Trench Warfare 1914-1918: The live and let live system (Pan Grand Strategy Series) 1979.

• RB., Tommy Atkins’ hidden tactics to avoid combat on the Western Front in WW1 or Why ‘Blackadder Goes Forth’ could have been a lot funnier (and more subversive)…

• M. Brown and S. Seaton, The Christmas Truce: The Western Front, December 1914, Leo Cooper, London 1984, 1994, empiricist, explicitly rejects Marxist interpretations, but good narratives and well referenced.

• David Englander and James Osborne , Jack, Tommy, and Henry Dubb: The Armed Forces and the Working Class (1978) The Historical Journal, 21, p.593-4

• P. Liddle (ed.), Passchendaele in Perspective: The Third Battle of Ypres, Pen and Sword, Barnsley 1997, a chapter by P. Scott on law and order ascribes low level of dissent to deferential attitude of Tommies.

• Marc Ferro, Malcolm Brown, Remy Cazals, Olaf Mueller. Meetings in No Man’s Land Christmas 1914: Fraternization in the Great War. Constable & Robinson 2007 ISBN 978-1-84529-513-4. 264 pp

• Anonymous, A German Deserter’s War Experience, published in Britain in 1917! It’s an account of the horrors of WW1, and a fair amount of resistance to it, written by an anonymous German deserter who fought in the trenches in France. It ends with a call for the overthrow of capitalism, and even has a chapter entitled “Soldiers shooting their own officers”. What more do you want…?

http://www.gwpda.org/memoir/Deserter/GermanTC.htm

Kindle and epub versions: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/42721

Conscientious objectors/resistance to conscription

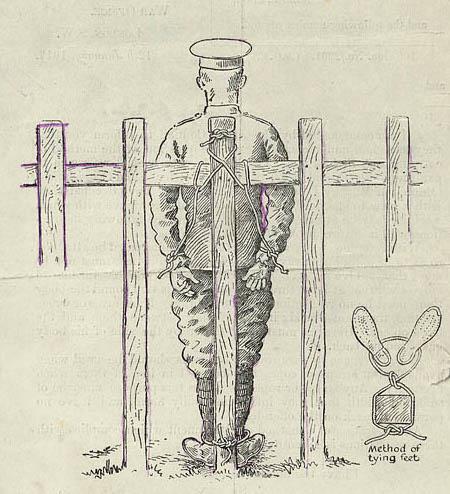

• A. Baxter, We Will Not Cease, Victor Gollancz, London 1939, an autobiography of an NZ ‘conchie’, details army punishments in France and Flanders during the First World War.

• John Taylor Caldwell, Come Dungeons Dark: The Life & Times of Guy Aldred, Glasgow Anarchist. (Luath Press, 1988). Has 11 chapters on the struggle of Aldred and others against the war, including resistance inside prisons by draft-refusers and conscientious objectors.

• Edwin H. Dare, Bread and Roses: Politics and Co-operation.

The story of Bermondsey Co-operative Bakery, a South London workers’ Co-op, with a very brief reference to its employing of conscientious objectors on the run during WW1.

• Will Ellsworth-Jones, We Will Not Fight: the untold story of World War One’s conscientious objectors. London, Aurum, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84513-403-7. 296 pp.

• Thomas C. Kennedy, The Hound of Conscience, (1981), University of Arkansas Press, 0938626019, ISBN 0938626019

• Cyril Pearce, Comrades in Conscience.

Now out of print. Publishers site: http://www.francisboutle.co.uk/pages.php?cID=5&pID=144

Grauniad review:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2002/feb/23/historybooks.highereducation1

• Crabbed Age and Youth, A Divine Comedy of the Watford Tribunal.

http://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/1910s/1916/no-141-may-1916/crabbed-age-and-youth

Trials and Executions of Deserters, Mutineers etc

• Anthony Babington, For the Sake of Example. Pen & Sword, 1993. 256pp.

• Piet Chielen and Julian Putkowski, Unquiet Graves. Basically this is guide book for a tour of the sites connected to executions in the Ieper (Ypres) area during the first World War.

• Gordon Corrigan, Mud, Blood and Poppycock (London: Weidenfeld Military. 2004) ISBN 978-0-304-36659-0

• Andrew Godefroy, For Freedom and Honour? The Story of 25 Canadians Executed During the Great War (Toronto: CEF Books, 1998) ISBN 1-896979-22-X

• John Hughes-Wilson, Blindfold and Alone: British Military Executions in the Great War. Phoenix, 2005. 544pp.

• David Lister, Die Hard, Aby!, (England: Pen & Sword, 2005) ISBN 978-1-84415-137-0

• William Moore, The Thin Yellow Line, (London: Wordsworth. 1999) ISBN 978-1-84022-215-9

• Nicolas Offenstadt, Les fusillés de la Grande Guerre (Paris: Éditions Odile Jacob, 1999)

• Gerard Oram, Death Sentences passed by military courts of the British Army 1914–1924, (UK: Francis Boutle Publishers, 1999) ISBN 1-903427-26-6

• Gerard Oram, Worthless Men, (November 1998), Francis Boutle Pub, 0953238830, ISBN 97809538835

• Gerard Oram, (2000),“What alternative punishment is there?”: military executions during World War I. PhD thesis, The Open University

• Denis Rolland, La grève des tranchées, Paris, Imago, 2005.

• Chris Pugsley, On the Fringes of Hell (1991: Hodder & Stoughton) ISBN 978-0-340-53321-5

• Julian Putkowski & Julian Sykes, Shot at Dawn: Executions in World War One by Authority of the British Army Act, (England: Pen & Sword, 1996) ISBN 978-0-85052-613-4

• Julian Putkowski & Gerard Oram, British Army Officers’ Courts Martial: 1914–1924. Francis Boutle Publishers, 2000.

• Julian Putkowski & Mark Herber, Military Criminals. Francis Boutle Publishers, 2001.

• Leonard Sellers, For God’s Sake Shoot Straight! (Leo Cooper, London, UK, 1995) (an account of the trial and execution of Royal Navy officer Sub-Lt Edwin Dyett)

• Ernest Thurtle, Military discipline and democracy, (London: Daniel Books. 1920)

• Ernest Thurtle, Shootings at dawn: The Army death penalty at work, (Pamphlet)

Resistance on the Home Front

• Fenner Brockway, Bermondsey Story, The Life of Alfred Salter. Has some accounts of anti-war activity/conscientious objection in the South London borough of Bermondsey.

• Gertrude Bussey and Margaret Tims, Pioneers for Peace: Women’s International league for Peace and Freedom, 1915-65. (1965) Self-published.

• Julia Bush, Behind the Lines: East London Labour 1914-1919 (Merlin Press, 1984).

• Francis Ludwig Carsten, War Against War: British and German Radical Movements in the First World War. Univ of California Pr./Batsford (1982)

• Anthony James Coles, The Moral Economy of the Crowd: Some Twentieth-Century Food Riots (food riots in Cumberland 1916-17), Journal of British Studies, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Autumn, 1978), pp. 157-176 Published by: Cambridge University Press

• Barbara Engel, Subsistence riots in Russia during World War I. Article on food riots, mostly by women, during World War I which helped spark the Russian revolution [and therefore end the war]. – 15pp. http://libcom.org/history/subsistence-riots-russia-during-world-war-i-barbara-engel

• Nick Heath, Anarchists against World War One: Two little known events- Abertillery and Stockport.

http://www.libcom.org/history/anarchists-against-world-war-one-two-little-known-events-abertillery-stockport

• Harry McShane, No Mean Fighter. (1978) Pluto Press. Autobiography of Scottish communist, with brief details of anti-war movement in Glasgow, (and interesting accounts of post-WW1 unemployed movement, the Communist Party and more.)

• Keith Robbins, The Abolition Of War: The Peace Movement in Britain 1914-1919. Cardiff: University Of Wales Press (1976)

• Dave Russell, Southwark Trades Council: A Short History 1903-78. Contains an account of local resistance to World War 1 in Camberwell, South London (reproduced in Rare Doings at Camberwell, past tense, 2008.)

• Sylvia Pankhurst, The Home Front.

• Bernard Waites (1987), A Class Society at War, 1914-18. (Leamington Spa, 1987.) Berg, 0907582656, ISBN 0907582656

• Ken Weller, Don’t be a soldier: the radical anti-war movement in North London 1914-18. (London, 1985.)

• John Williams, The Other Battleground: The Home Fronts, Britain, France and Germany, 1914-18 (1972)

• Barbara Winslow, Sylvia Pankhurst (1996)

• The Battle of Cory: Patriots Meet Dissenters in Cardiff. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+Battle+of+Cory+Hall,+November+1916%3A+Patriots+Meet+Dissenters+in…-a063583862

Wartime Repressive Measures in Britain

• Brock Millman, Managing Dissent in First World War Britain

The last chapter deals with the stationing of a million and a half troops in Jan 1918 at strategic points across Britain near industrial centres as the authorities became fearful of dissent and revolution – slightly problematic when combined with the threat of mutiny. They also had the problem of trying to fight a war in Europe!

• Margaret Flaws, Spy Fever: The Post Office Affair. Published by The Shetland Times at £14.99. (2009). A remarkable true story of the events surrounding the unexplained incarceration of the entire staff of the Lerwick Post Office at the beginning of the First World War.

• Panikos Panayi, Prisoners of Britain : German civilian and combatant internees during the First World War. http://www.worldcat.org/title/prisoners-of-britain-german-civilian-and-combatant-internees-during-the-first-world-war/oclc/799144766&referer=brief_results

• Panikos Panayi, The enemy in our midst: Germans in Britain during the First World War (1991) http://www.worldcat.org/title/enemy-in-our-midst-germans-in-britain-during-the-first-world-war/oclc/20798306&referer=brief_results

Jingoism, Racism and Chauvinism

• Stephen Bourne, Black Poppies: Britain’s Black Community and the Great War. (To be published 1 August 2014)

• Pat O’Mara, The Lusitania Riots of May 1915: A personal account. http://www.libcom.org/history/lusitania-riots-may-1915-personal-account-pat-omara

Effects of war on soldiers

• Anthony Babington, Shell Shock: A History of the Changing Attitudes to War Neuroses.(Leo Cooper, 1997)

• JMW Binneveld, From Shell Shock to Combat Stress. (Amsterdam University Press, 1997)

• Ted Bogacz, War Neurosis and Cultural Change in England, 1914-22. (Journal of Contemporary History, volume 24, 1989)

• Joanna Bourke, Dismembering the Male: Men’s Bodies, Britain and the Great War. (Reaktion Books, 1996)

• Eric J Leed, No Man’s Land: Combat and Identity in World War One. (Cambridge University Press, 1979)

• Peter Leese, Problems Returning Home: The British Psychological Casualties of the Great War. (The Historical Journal, volume 40, 1997)

• Derek Summerfield, The invention of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category. British Medical Journal, January 13, 2001, available at <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1119389/>.

Impact of the War: Studies of Society at War (and peace)

• Wolfgang J Mommsen, Imperial Germany, 1867-1918: Politics, Culture and Society in an Authoritarian State.

• N. P. Howard, The Allied Food Blockade of Germany, 1918-19. (http://libcom.org/history/allied-food-blockade-germany-1918-19-n-p-howard)

Women and World War One

• Womens Web (Australia) Womens Stories – Womens Actions. “Remembering ANZAC” http://www.womensweb.com.au/ANZAC.html

• “Prejudice and Reason”. Some Australian Womens responses to war from 1909 to now. Includes ‘2 Women and 2 Journals during WW1’ on support for and opposition to the war. http://www.prejudiceandreason.com.au/index.html

• Karen Hagemann, Home/Front; the Military, War and Gender in Twentieth Century Germany.

• Gail Braybon, Evidence, History and the Great War.

• Ute Daniel, The War from Within: German Women in the First World War.

• Laura Lee Downs, Manufacturing Inequality: Gender Division in the French and British Metalworking Industries, 1914-39.

• Kate Adie, Fighting on the Home Front: the legacy of women in World War One. Hodder & Stoughton, 2013. 328pp. Wide-ranging, includes a lot about Sunderland.

Immediate Post-war Scene/resistance to Intervention in Russia• Andre Marty, The Epic of the Black Sea (on the Black Sea revolt).

• Chanie Rosenberg, 1919: Britain on the Brink of Revolution, Bookmarks, London 1987.

• Guy Sabatier, The 1918 treaty of Brest-Litovsk: curbing the revolution

http://www.libcom.org/history/1918-treaty-brest-litovsk-curbing-revolution-guy-sabatier

• Dan Weinbren, Revolution at the Arsenal: the Campaign for alternative work at the Woolwich Arsenal after the First World War. (South London Record).

The End of the War, and how it was Celebrated

• Practical History, Churchill, the Cenotaph and May Day 2000. (http://libcom.org/history/churchill-cenotaph-may-day-2000-practical-history)

When did the War Really End?

According to one source the technical date of termination of the war was not until August 1921! Prolonging the war was used to keep people in arms to try to intervene in Russia, as well as to extend repressive powers, eg the vicious Defence of the Realm Act, criminalising dissent, allowing for harsher sentences etc…

See:

• http://www.circlecity.co.uk/wartime/board/index.php?page=88

•https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Termination_of_the_Present_War_(Definition)_Act_1918

• http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/revhist/backiss/vol8/no2/putkowski2.html

WW1 to WW2: Did one lead to the other…?

• Arno Mayer

, The Persistence of The Old Regime.

WW1 In Fiction

• Pat Barker, The Regeneration Trilogy:

– Regeneration

– The Eye in the Door

– The Ghost Road

• Henri Barbusse, Under Fire (1916)

• A T Fitzroy, Despised and Rejected.

(pseudonym of Rose Allatini) whose central characters are a gay conscientious objector and his lesbian/bisexual anti-war woman friend. This was originally published by CW Daniel in 1918 before being banned under DORA, and was reprinted by Gay Men’s Press in the 1980s, and again quite recently by a small US press. It appears to be out of print, but there’s extracts on google books: http://is.gd/giRtdx

and Amazon: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Despised-Rejected-A-T-Fitzroy/dp/0922558485#reader_0922558485

• Lewis Grassic Gibbon, Sunset Song (1932)

• Jaroslav Hasek, The Good Soldier Svejk in the World War

• Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front (1928)