Phil Woolas should stop worrying about poor people’s fertility and tackle the real ‘extremely thorny’ question – rich people’s wealth, says Bob Hughes

After thirty years of well-earned exile in the moral wilderness, population politics is back. For Sir Andrew Green of Migration Watch, immigration minister Phil Woolas’s headline-grabbing interview with The Times on 18 October 2008 was the turning point: ‘It is the first time that a government minister has actually linked immigration and population.’

sir andrew green - posh scumbag

Population politics doesn’t only threaten immigrants. It’s an us-and-them game where anybody can be ‘it’. If you become unemployed or a bit too ill, you may cease to be an individual with rights, and become part of a ‘population’ instead, and a suitable case for ‘management’. Nothing could make this plainer than the juxtaposition, in The Sun (8 December 2008), of Woolas’s latest pronouncement that ‘Immigrants will have to earn the right to UK benefits and council housing … [and] wait ten years before they get a penny’, with work and pensions secretary, James Purnell’s equally tough pronouncement that from now on ‘nearly all benefit claimants will be forced to work in exchange for state handouts’.

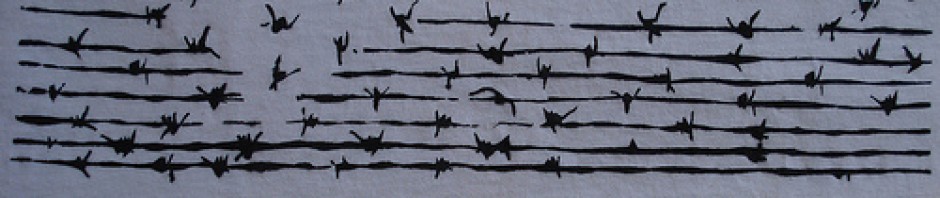

Population politics implies the ‘legalisation’ of humanity: the right to be treated as if one were human is conferred only by thorough legal process; it cannot be acquired lightly, for example by being born, or conceived, or just turning up on one’s own unauthorised, autonomous initiative.

As the Columbia University historian, Matthew Connelly shows in his new book on the subject (Fatal Misconception: the struggle to control world population; Belknap, 2008), birth-control and immigration control are the two faces of population politics. Some very bizarre and unattractive obsessions lie at its heart, including a sordid preoccupation with other people’s breeding habits – especially of ‘the poor’.

During a BBC Radio 3 discussion of neo-Malthusianism in ‘today’s crowded world’, in March this year, Connelly said:

‘Too often, alas, population projections are psychological projections … not that there are too many people but that there certain kinds of people, with whom we feel uncomfortable, who there are too many of. So when people say the US or the UK for that matter is overpopulated I want to ask them which people in particular they have in mind, who are in and of themselves a problem?

‘If the problem is consumption, then of course it’s the wealthiest people we need fewer of. I mean, Britain would do much better if it had 100 million subsistence farmers, say, than 50 million people who are doctors and lawyers and bankers and so on. It could have much less of a carbon footprint if it imported subsistence farmers from the Sahel, and exported bankers and lawyers to Africa. But nobody is proposing that’

Alas, Woolas isn’t proposing that. Instead, he seems hell-bent on subjecting us all to the same ghastly philosophy of population control and the warped psychology that drives it, that Connelly describes in his book.

Drawing on a previously untouched wealth of primary evidence (including private letters, minutes, and interviews with surviving actors in these dramas), Connelly follows the global population-control epidemic back to its origins in the USA in the El Niño years of the 1870s. Global climate and colonialism induced catastrophes were met head-on by new, toxic orthodoxies. Nascent eugenics, plus the teachings of Thomas Malthus, and ‘political projects to define nationalism and delimit citizenship through both state policies and popular violence’, as well as ‘faceless bureaucracies that were not even accountable to the federal courts’ (p.37).

Sounds familiar? The recent Queen’s speech, with its promise of even greater Home Office powers, should be a wake-up call for anyone who has still not noticed Britain’s expanding, parallel incarceration system, with its own dedicated networks of reporting centres and special, ever less accountable courts. Woolas’s pronouncements, since his arrival in Parliament as a Mandelson protegé a decade ago, have struck echo after echo from that Edwardian past: not just the obsession with human numbers (and the grandiose promise to limit the UK’s population to under 70 million); but also a textbook obsession with his Asian constituents’ breeding habits (his crusade against first-cousin marriages); and constant, gentle appeals to the threat of popular violence (in his case, from the not-very-popular BNP).

Just as in California in the late Nineteenth-century, all of this is done in the name of that most essential McGuffin of population politics: the ‘Indigenous Working Class’. (The only kind of working class population politicians acknowledge.) Woolas gives voice to their anger, when immigrants are (extremely rarely, he affirms, but mentions it anyway) given million pound houses at taxpayers’ expense; and at Muslim women who divide the community by wearing the hijab. These issues are raised as an ‘unfortunate duty’ that falls to him because others lack the guts to do it. He calls them ‘thorny issues’. We are tempted not to notice his failure to raise other thorny issues, such as the extraordinary shortage of decent housing and jobs in the very constituency he represents.

A shameful history

Today’s population controllers are a scary and powerful lot. But they have a great weakness in their own history, inextricably bound up with the massive, ghastly fertility control campaigns Connelly describes; always aimed at the poor, not just in poor countries, but also in the USA, Sweden and all over the world. It was a war (described and conducted as such, often by military men such as the USA’s General William Draper and China’s Xinzhong Qian) that ruined millions upon millions of lives – yet had no particular effect in the end on numbers: growth was already declining. ‘It turns out that about 90 percent of the difference in fertility rates worldwide derived from something very simple and very stubborn: whether women themselves wanted more or fewer children.’ All the evidence so far suggests that attempts to control world migration are equally futile. Will they meet the same fate, and if so, at whose hands?

At the apparent height of its power, the population control bandwagon suddenly collapsed. First, it hit mounting, massive grassroots resistance; then came the global reproductive rights movement, which utterly routed it at the UN’s Population Conference in Cairo in 1994. Population control became a tar baby. Organisations that had backed coercion, transformed themselves into champions of autonomy overnight. Others changed their names. The American Eugenics Society became the Society for the Study of Social Biology; Eugenics Quarterly became Social Biology. In the UK, in 1988, the Eugenics Society renamed itself The Galton Institute (after the founder of Eugenics, Francis Galton).

Will the wheels fall off ‘managed migration’ in similar fashion? This too is being challenged increasingly by the people it oppresses. And the bigger it gets, the harder it becomes to conceal its shameful underpinnings.

Migration Watch craves the spotlight but also fears it. It has fought hard to stop people knowing that its co-founder, Oxford University’s Professor David Coleman, has been a lifelong member of the Eugenics Society, and one of its high officials during the decades when sterilisation campaigns were at their peak. What, if any, part did he play in all that? He is known to have been a government adviser during the 1980s and examined the then fashionable question of state benefits for single, working-class mothers. But when this aspect of his past was brought to public notice by students in early 2007, his response was not to answer their concerns but to pillory them as ‘tyrannical’. The Daily Telegraph gave him a whole page in which to vent his indignation – which he managed to do without mentioning eugenics once, let alone explaining his role in it.

Increasingly people know about this connection and they cannot help joining the increasingly plentiful dots. Migration Watch’s other autumn coup – getting the imprimatur of a cross-party Parliamentary group (albeit an unofficial one) for their Balanced Migration report – came at the price of public association with anti-abortionist, anti-assisted pregnancy obsessive, Frank Field (not to mention the widely abhorred Nicholas Soames).

All the makings are here for the badly needed, total and indeed comical rout of Woolas, Smith, Green, Coleman, Field and all their friends and minions – and their replacement by people with the guts to tackle the real ‘thorny issue’: the rich.

Bob Hughes, No One Is Illegal

Notes:

Fatal Misconception: the struggle to control world population; Matthew Connelly; Belknap/Harvard University Press 2008. Free sample chapter, here

The quotation above was transcribed from BBC Radio 3 Nightwaves, 19 March 2008

On unaccountable bureaucracies, Connelly cites Adam McKeown’s new book ‘Melancholy Order: Asian migration and the globalization of borders, 1837-1937’

The Woolas interview, ‘Phil Woolas: lifelong fight against racism inspired limit on immigration.’ and comment (Times 18/10/2008) are here and here

For many further sources see

Shiar Youssef’s analysis, on Indymedia (‘Immigration crunch? The Times’ and BBC’s anti-immigration agendas’) with links to his ‘anti-white racism’ and ‘inbred Muslim’ announcements:

David Osler’s blog ‘He’s not racist, but …’(21/10/2008)

‘Migrants to earn dole and house’ _ The Sun, 8 Dec 2008

A Shorter version of this article appeared in decembers issue of red pepper

The American eugenics society has renamed itself and its journal again.

The new journal name is Biodemography and Social Biology; the Society will become The Society of Biodemography and Social Biology. Biodemography means regarding all biology from the standpoint of populations and their survival characteristics. The change is caused primarily by the failure of the Theory of the Demographic Transition promoted by population controller eugenicists to predict either low, low fertility or extended life spans as a world wide phenomenon.

A new list of Society members and possible members is up at Scribd: Google , Biodemography and Social Biology + Lindberg