Month: May 2011

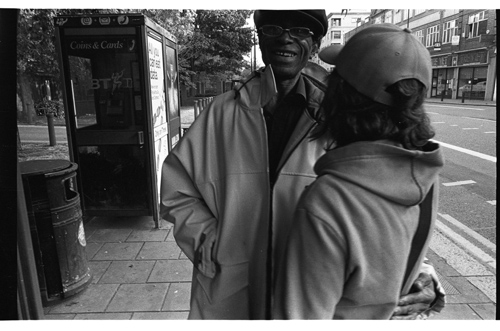

28/5/11-

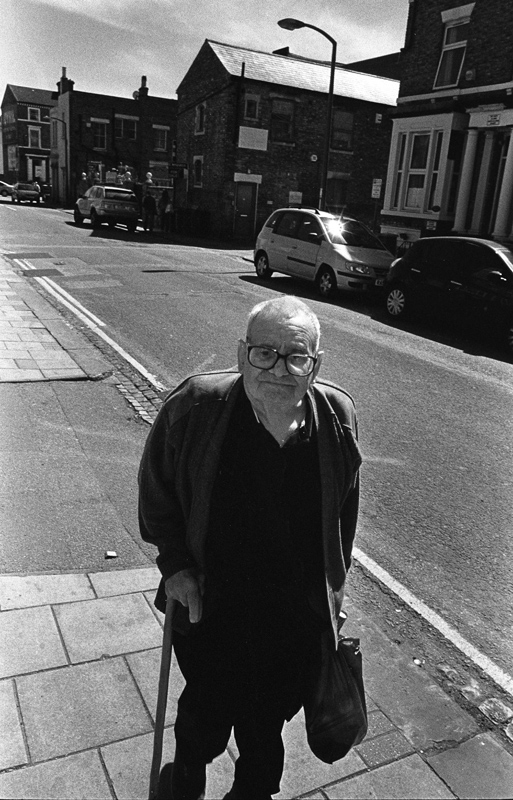

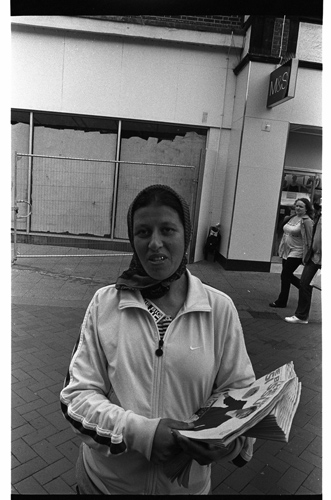

28/5/11-

midland road + alexandra road..

Bang Bang Club Members Discuss Perils of Combat Photography.

On Tuesday, one day before the deaths of two photojournalists in Libya made headlines around the world, “Fresh Air”‘s Terry Gross sat down with combat photographers Greg Marinovich and Joao Silva, both of whom have been seriously injured while working in the field. Silva lost both of his legs when he stepped on a land mine in Afghanistan while embedded with an infantry decision alongside a New York Times reporter. He is currently recovering at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

The two friends together are part of “The Bang-Bang Club” – a group of four photographers who documented the final years of South African apartheid. The collaborated on a memoir of that experience called “The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots from a Hidden War” which has been turned into a movie starring Ryan Phillipe.

The wide-ranging interview will be fascinating to anyone with an interest in combat photography. Highlights include:

Greg Marinovich on the ethics of war photography

“The other thing that photographers struggle with is the setting up of pictures. And by that, I mean, where the photographer interferes in the scene to make it a better picture — where essentially fiction and nonfiction blur — that we have real problems with. I remember a very famous New York-based photographer was at the funeral of Chris Hani, the communist leader who was assassinated by white extremists. He was directing the show to make for a better picture, and we all immediately wrote to his employer — his contract employer at the time was Time magazine — and he was pulled off the job immediately. And this other photographer we spoke about — the right-winger — he would hire a Mercedes-Benz and drive into the township and drive up and down the volatile areas until people started stoning his cars so that he could get the pictures.”Greg Marinovich on the difficulties of publishing his 1991 Pulitzer Prize-winning series of photos, which showed a man attacked with a machete and then set on fire in South Africa

“I didn’t try and get it published. At the time I was freelancing, and I was shooting for the AP and also for Sigma, the photo agency. And so I had two separate cameras. One had color negative for AP and one had color slide for Sigma. And the AP put the pictures up. They put up 18 pictures in all. And newspapers complained about the graphic nature of those pictures, and many didn’t publish those pictures. It wasn’t that the ‘burning man’ wasn’t widely published at all — certainly not in South America and not in America, and I can understand that; they are very disturbing pictures, and that’s up for a newspaper to decide what they want to publish — but the tangential argument from that is that it’s not up to us as photographers to censor that. It’s not up to us to not shoot it because it’s too graphic or too disturbing. It’s not up to us to not edit that and put that in the take, and it’s certainly not up to the distributing agency to decline to put those pictures in the take because of their graphic nature. In fact, it was the New York office of the AP that almost didn’t want to move those pictures on. Because London had taken them in … and in New York, it was difficult. They almost didn’t move the picture.”

Listen to Gross’s interview and see a slideshow of their photographs here.

The movie will be screening as part of the Tribeca Film Festival. You can find out more about the film and where you can see it at its website. The film’s trailer is below.

Bang Bang Club Members Discuss Perils of Combat Photography.

On Tuesday, one day before the deaths of two photojournalists in Libya made headlines around the world, “Fresh Air”‘s Terry Gross sat down with combat photographers Greg Marinovich and Joao Silva, both of whom have been seriously injured while working in the field. Silva lost both of his legs when he stepped on a land mine in Afghanistan while embedded with an infantry decision alongside a New York Times reporter. He is currently recovering at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

The two friends together are part of “The Bang-Bang Club” – a group of four photographers who documented the final years of South African apartheid. The collaborated on a memoir of that experience called “The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots from a Hidden War” which has been turned into a movie starring Ryan Phillipe.

The wide-ranging interview will be fascinating to anyone with an interest in combat photography. Highlights include:

Greg Marinovich on the ethics of war photography

“The other thing that photographers struggle with is the setting up of pictures. And by that, I mean, where the photographer interferes in the scene to make it a better picture — where essentially fiction and nonfiction blur — that we have real problems with. I remember a very famous New York-based photographer was at the funeral of Chris Hani, the communist leader who was assassinated by white extremists. He was directing the show to make for a better picture, and we all immediately wrote to his employer — his contract employer at the time was Time magazine — and he was pulled off the job immediately. And this other photographer we spoke about — the right-winger — he would hire a Mercedes-Benz and drive into the township and drive up and down the volatile areas until people started stoning his cars so that he could get the pictures.”Greg Marinovich on the difficulties of publishing his 1991 Pulitzer Prize-winning series of photos, which showed a man attacked with a machete and then set on fire in South Africa

“I didn’t try and get it published. At the time I was freelancing, and I was shooting for the AP and also for Sigma, the photo agency. And so I had two separate cameras. One had color negative for AP and one had color slide for Sigma. And the AP put the pictures up. They put up 18 pictures in all. And newspapers complained about the graphic nature of those pictures, and many didn’t publish those pictures. It wasn’t that the ‘burning man’ wasn’t widely published at all — certainly not in South America and not in America, and I can understand that; they are very disturbing pictures, and that’s up for a newspaper to decide what they want to publish — but the tangential argument from that is that it’s not up to us as photographers to censor that. It’s not up to us to not shoot it because it’s too graphic or too disturbing. It’s not up to us to not edit that and put that in the take, and it’s certainly not up to the distributing agency to decline to put those pictures in the take because of their graphic nature. In fact, it was the New York office of the AP that almost didn’t want to move those pictures on. Because London had taken them in … and in New York, it was difficult. They almost didn’t move the picture.”

Listen to Gross’s interview and see a slideshow of their photographs here.

The movie will be screening as part of the Tribeca Film Festival. You can find out more about the film and where you can see it at its website. The film’s trailer is below.

Bang Bang Club Members Discuss Perils of Combat Photography.

On Tuesday, one day before the deaths of two photojournalists in Libya made headlines around the world, “Fresh Air”‘s Terry Gross sat down with combat photographers Greg Marinovich and Joao Silva, both of whom have been seriously injured while working in the field. Silva lost both of his legs when he stepped on a land mine in Afghanistan while embedded with an infantry decision alongside a New York Times reporter. He is currently recovering at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

The two friends together are part of “The Bang-Bang Club” – a group of four photographers who documented the final years of South African apartheid. The collaborated on a memoir of that experience called “The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots from a Hidden War” which has been turned into a movie starring Ryan Phillipe.

The wide-ranging interview will be fascinating to anyone with an interest in combat photography. Highlights include:

Greg Marinovich on the ethics of war photography

“The other thing that photographers struggle with is the setting up of pictures. And by that, I mean, where the photographer interferes in the scene to make it a better picture — where essentially fiction and nonfiction blur — that we have real problems with. I remember a very famous New York-based photographer was at the funeral of Chris Hani, the communist leader who was assassinated by white extremists. He was directing the show to make for a better picture, and we all immediately wrote to his employer — his contract employer at the time was Time magazine — and he was pulled off the job immediately. And this other photographer we spoke about — the right-winger — he would hire a Mercedes-Benz and drive into the township and drive up and down the volatile areas until people started stoning his cars so that he could get the pictures.”Greg Marinovich on the difficulties of publishing his 1991 Pulitzer Prize-winning series of photos, which showed a man attacked with a machete and then set on fire in South Africa

“I didn’t try and get it published. At the time I was freelancing, and I was shooting for the AP and also for Sigma, the photo agency. And so I had two separate cameras. One had color negative for AP and one had color slide for Sigma. And the AP put the pictures up. They put up 18 pictures in all. And newspapers complained about the graphic nature of those pictures, and many didn’t publish those pictures. It wasn’t that the ‘burning man’ wasn’t widely published at all — certainly not in South America and not in America, and I can understand that; they are very disturbing pictures, and that’s up for a newspaper to decide what they want to publish — but the tangential argument from that is that it’s not up to us as photographers to censor that. It’s not up to us to not shoot it because it’s too graphic or too disturbing. It’s not up to us to not edit that and put that in the take, and it’s certainly not up to the distributing agency to decline to put those pictures in the take because of their graphic nature. In fact, it was the New York office of the AP that almost didn’t want to move those pictures on. Because London had taken them in … and in New York, it was difficult. They almost didn’t move the picture.”

Listen to Gross’s interview and see a slideshow of their photographs here.

The movie will be screening as part of the Tribeca Film Festival. You can find out more about the film and where you can see it at its website. The film’s trailer is below.

Global capitalism and 21st century fascism – Opinion – Al Jazeera English

Global capitalism and 21st century fascism – Opinion – Al Jazeera English.

“The Obama project from the start was an effort by dominant groups to re-establish hegemony in the wake of its deterioration during the Bush years (which also involved the rise of a mass immigrant rights movement). Obama’s election was a challenge to the system at the cultural and ideological level, and has shaken up the racial/ethnic foundations upon which the US republic has always rested. However, the Obama project was never intended to challenge the socio-economic order; to the contrary; it sought to preserve and strengthen that order by reconstituting hegemony, conducting a passive revolution against mass discontent and spreading popular resistance that began to percolate in the final years of the Bush presidency.

The Italian socialist Antonio Gramsci developed the concept of passive revolution to refer to efforts by dominant groups to bring about mild change from above in order to undercut mobilisation from below for more far-reaching transformation. Integral to passive revolution is the co-option of leadership from below; its integration into the dominant project. Dominant forces in Egypt, Tunisia, and elsewhere in the Middle East and North America are attempting to carry out such a passive revolution. With regard to the immigrant rights movement in the United States – one of the most vibrant social movements in that country -moderate/mainstream Latino establishment leaders were brought into the Obama and Democratic Party fold – a classic case of passive revolution – while the mass immigrant base suffers intensified state repression.”

Global capitalism and 21st century fascism – Opinion – Al Jazeera English

Global capitalism and 21st century fascism – Opinion – Al Jazeera English.

“The Obama project from the start was an effort by dominant groups to re-establish hegemony in the wake of its deterioration during the Bush years (which also involved the rise of a mass immigrant rights movement). Obama’s election was a challenge to the system at the cultural and ideological level, and has shaken up the racial/ethnic foundations upon which the US republic has always rested. However, the Obama project was never intended to challenge the socio-economic order; to the contrary; it sought to preserve and strengthen that order by reconstituting hegemony, conducting a passive revolution against mass discontent and spreading popular resistance that began to percolate in the final years of the Bush presidency.

The Italian socialist Antonio Gramsci developed the concept of passive revolution to refer to efforts by dominant groups to bring about mild change from above in order to undercut mobilisation from below for more far-reaching transformation. Integral to passive revolution is the co-option of leadership from below; its integration into the dominant project. Dominant forces in Egypt, Tunisia, and elsewhere in the Middle East and North America are attempting to carry out such a passive revolution. With regard to the immigrant rights movement in the United States – one of the most vibrant social movements in that country -moderate/mainstream Latino establishment leaders were brought into the Obama and Democratic Party fold – a classic case of passive revolution – while the mass immigrant base suffers intensified state repression.”