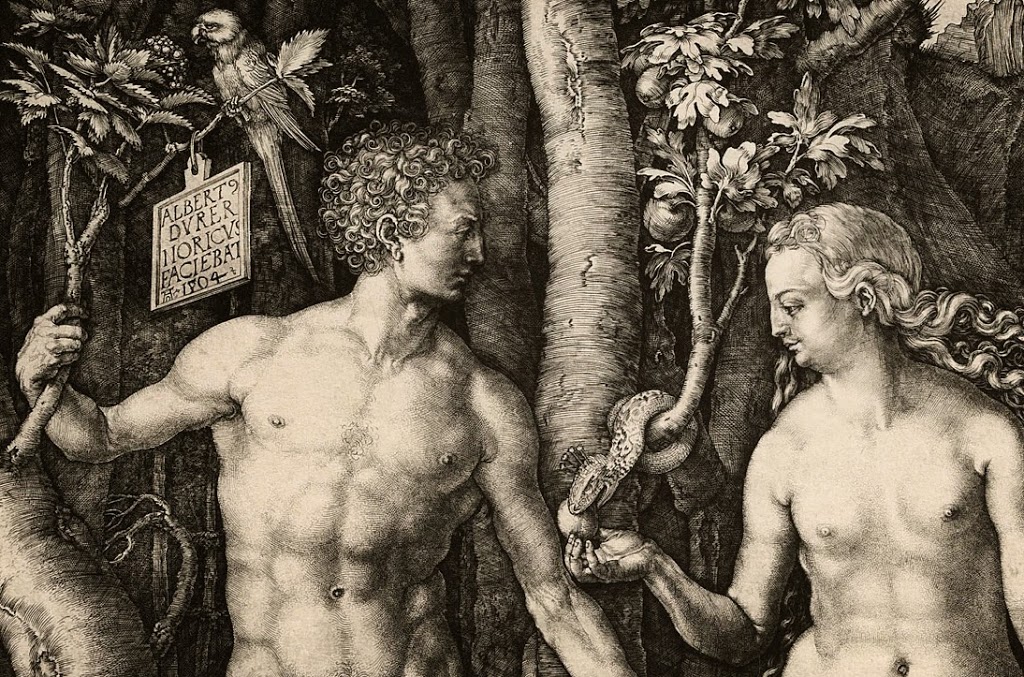

There could hardly be a more poisonous concept with which to pollute the human soul than that of Original Sin.

The story of the Garden of Eden was used by the Christian Church to create the doctrine that each and every one of is essentially bad.

According to this belief, it is only through the salvation offered by Christ, and thus by servile obedience to the powerful multinational organisation which represents His interests here on Earth, that we can hope to escape eternal damnation.

Today, with the influence of the Church generally on the wane, most of us no longer consider ourselves to be miserable sinners.

In many ways, though, the toxicity of Original Sin has lingered on in new contemporary forms.

The reactionary political philosophy of Thomas Hobbes has merged with right-wing neo-Darwinist ideas, with a bit of Freud thrown in, to produce a view of humanity every bit as bleak as that of the Church.

This was lent further currency by William Golding’s appalling Lord of the Flies, in which the (fictional) horrific cruelty of a bunch of unsupervised children is meant to reveal the horrific cruelty at the heart of uncontrolled human nature.

According to this outlook, we are all intrinsically bad. The answer to this, as Hobbes spelled out explicitly, is that our lives must be tightly controlled and governed by Authority. Otherwise, who knows what we would all descend into…

This is, of course, a fundamentally right-wing position to take. And yet to some extent it is also accepted by much of what is termed the “Left”, including anarchists, particularly in the view that education is necessary to teach us how to live with others in a respectful and sharing way.

Some of the confusion perhaps arises from the difference between children and adults, and the process of growing up.

Golding skilfully exploited this confusion to pernicious effect with his malignantly influential novel, playing on our memories of playground nastiness to paint the soul of humankind in the darkest of shades.

But children are not the finished product. Neither, for that matter, are 23 year olds, or 51 year olds. We go through stage after stage of psychological development throughout our lifetimes – or at least, we should do, if we are to fully become ourselves.

The potential to grow in this way, to become what we can be, is there inside us all along, though initially empty of actual content – as with Noam Chomsky’s idea of the innate ability to learn language.

The question of whether or not we are able to fulfil that potential, or what part of it we can fulfil, is determined by our environment. Likewise, the actual language or languages that we pick up, using our innate ability, depends on what languages we hear around us at a formative age.

Today we tend to think of the learning environment that is necessary for our mental stimulation and development in terms of “education”.

Over the last 150 years or so, anarchists have been at the forefront of radical changes in how we perceive that term and it has moved away from the rigid disciplines of learning-by-rote that were once imposed on youngsters.

But it is important to remember that the root meaning of the word “educate” is to “lead out”. It is not so much about pouring content into the mind (except in terms of specific facts), as in allowing or prompting innate abilities and possibilities to emerge from within. Our concept of education remains, therefore, a little narrow.

In his excellent book Nature and Madness, Paul Shepard explains how the development of an individual – their ontogeny – is meant to be closely linked to the natural world and the stages of life through which we have evolved to pass.

He argues that present in all of us is the “seed of normal ontogeny” which, if allowed to grow properly, would see us develop “in a genetic calendar by stages, with time-critical constraints and needs, so that instinct and experience act in concert”.

Compared to these age-old rites of passage, deeply intertwined with the cyclical rhythms of nature, the sort of “education” we experience today is sorely limited by the constant impact of the modern world around us.

A person growing up in our industrial civilization is like a plant trying to grow on a sparse and unhealthy patch of earth, in a polluted atmosphere, where the sunlight is permanently blocked by concrete walls.

Just because the plant does not grow to its full glory, does not mean that the potential to do so was not contained within it.

And neither does it mean that the species is doomed forever to produce wilted and miserable specimens.

Once the pollution has cleared, once the concrete has crumbled and gone, then the plant will be free to drink in the sunshine, to soak up life-giving nutrients from the earth, to grow to its full potential and to burst into flower.

This is what the anarchist belief in the innately positive nature of humankind is all about. It is not a “naïve” belief that there could ever be a human society where everyone was nice to each other all the time, where nobody ever lost their temper, hurt someone or broke their heart.

Instead, it is a deep-seated conviction that we are all essentially, potentially, good; that life itself – nature, the universe, being – is essentially good.

“Good” is not something separate from us, something distant and superior that we need to worship, that we need to beg to rescue us from the domain of the Lord of the Flies to which we are innately condemned. It is our essence, our core, our sense of value and self-empowerment.

In opposition to this innate “goodness” is the whole environment which blocks its development, the flowering of its potential. This environment is not just the physical one of industrial society, which stunts and poisons us, but the mental environment of the ideas that surround us.

If somebody thinks that we are all born innately bad and that only subservience to organised religion can save us from hell, they have fallen prey to the lie of Original Sin.

If somebody thinks that without a strong state to keep them in line, human beings will degenerate into warring chaos, they have been contaminated by the negative ideology of Hobbes.

If somebody thinks that true human nature is essentially dark and that allowing it to manifest itself is dangerous, then they are also a victim of that mindset. (Ironically, although for the Left this feared inner darkness often takes the political form of the threat of fascism, it is a concept very much embraced by fascists, for whom this demonic force can be harnessed by their cause in its bid to gain power and thereafter can ultimately only be controlled and absorbed by their war-fixated totalitarian state).

If somebody thinks that through education the good qualities of humanity are introduced intoour minds, rather than teased out of them, then they have also been affected by that way of thinking, although obviously in a more subtle fashion.

There is still a certain reluctance there to turn Original Sin completely on its head, to trust nature, to trust our own beating hearts and flowing blood, to accept William Blake’s assurances that “Innate Ideas are in Every Man, Born with him; they are truly Himself”.

Leave a Reply