The powerful coherence of the anarchist philosophy means that it represents a significant threat to the intellectual domination of the capitalist system.

It stands outside all the assumptions on which that self-referential ideological edifice is built and the piercing clarity of its gaze risks fatally undermining the deceptions on which the status quo is built.

The defenders of injustice, inequality, repression and exploitation must therefore breathe a deep sigh of collective relief every time that anarchist thinking wanders a step further away from its core strengths and disappears up a dead-end of disempowerment and irrelevancy.

It is therefore heartening to see that some clear-thinking comrades in France have been trying to lift the theoretical fog in which anarchism currently risks becoming lost.

The commentaries in question are based around a book by Renaud Garcia called Le désert de la critique: déconstruction et politique, which was published by L’Échappée in Paris earlier this year.

An article by Freddy Gomez on the A Contretemps website explains that Garcia is a philosopher influenced by anarchism and the décroissance (degrowth) movement.

The task he takes on in his book is, says Gomez, “to establish how deconstruction theory has so widely helped legitimise the way in which the world has become commercialised and artificial”.

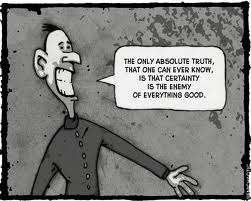

Gomez argues that the main effect of the deconstructionist outlook, sometimes known as French Theory in the English-speaking world, is to “annihilate all knowledge based on reason” and “on the ruins of this devastated and unfathomable landscape, to champion the fragmentary against the communal, diversity against equality, the undifferentiated against the universal, the societal against the social, gender against class and the masses against the people”.

In another discussion of Garcia’s work in the Radio Zinzine Info bulletin (and online here and here), Tranbert Harlou focuses particularly on the iniquitous role of a prevalent ideology loosely based on the thought of the philosopher Michel Foucault.

Harlou sums up this Foucaultian philosophy thus: “What we call truth and reality are only social and political constructions which serve to bolster positions of power and the domination of one group over another. Each group within society produces norms and ideology which allow it to exclude those who don’t conform and to justify either its domination or the inferior status imposed on it, its marginalisation or its stigmatisation.

“Also, in some way, power is not only located in state apparatus and in hierarchical institutions, but most importantly exists within every one of us. We have all internalised the norms and the views of a society which is capitalist, white, heterosexual, able-bodied, omnivorous, etc.

“As a consequence, any individual who wants to remain free, or groups who want to remove themselves from the circumstances in which they have been placed, must above all else focus on subverting norms and blurring the boundaries set up between different identities… even if this means themselves creating new norms which will constitute the basis of new groups. The most subversive approach is therefore not only to deconstruct identities by opposing them with alternative identities, but to go beyond identity itself through a permanent process of disidentification”.

As he says, there are useful elements in this sort of analysis. But the problem is that it has gained too strong a grip on anarchist thinking and risks eclipsing what should be the fundamental anarchist message.

What Gomez and Harlou both draw from Garcia’s book is that this Foucaultian approach (also based on the work of Deleuze, Guattari and others) is leading people away from a social critique of capitalism and towards an individualistic liberal outlook.

Harlou explores Garcia’s warning that postmodern ideology lays the way open to the idea of society as a vast machine in which the self-fulfilment of the individual cogs within that system has replaced any collective desire to break free.

An outlook which regards as problematic any identity beyond the individual level risks reducing people to a superficial and atomised awareness of their existence, cut off from any “restrictive” sense of essentially belonging to communities, to the human race or to nature.

It basically states, argues Harlou, that “the pursuit of individual happiness can be carried out to the detriment of collective freedom by reducing society to a system of automised production and equitable distribution of goods and services to emancipated consumers. In other words, capitalism with a human face. Glory Alleluia!”

Harlou says we should all be on our guard against any ideological drift that ends up, by circuitous routes, making us part of the system which we claim to oppose.

He warns: “Note that the Foucaultians see relationships between people as a struggle for life (or power), with overtones of a certain kind of social Darwinism. This is certainly a pretty pessimistic vision of human nature and society, which necessarily leaves little room for mutual aid, solidarity or for collective struggles and communities and puts great store on the ability of the individual to take advantage of the gaps and margins in the system in order to escape from it, at the expense of everyone else. Curiously, this vision just happens to be very much in line with the capitalist system which it claims to be criticising…”

Gomez points out that “French Theory” manages to simultaneously appeal to supporters of the current system and “the disciples of a transgressive postanarchism which has signed up to all the delusional drivel of this nihilistic ideology and is well on the way to becoming its avant-garde”.

It undermines any sense of coherence by turning language “in the same way that the police turn potential informants”.

He quotes the situationist Guy Debord in judging that they have “abandoned logic and with it the ability to instantly tell what is important and what is trivial or irrelevant; what is incompatible or what, on the other hand, could be complementary; what leads on from certain consequences and what is blocked”.

For Gomez, the postanarchism which has developed, mainly in the USA , since the 1990s, and which is spearheaded the likes of Todd May, Saul Newman, Lewis Call, Jason Adams and Richard Day, has nothing at all to do with “classical” anarchism.

“In fact, as with postfeminism, whose principal target is historical feminism, postanarchism comes across not as a contemporary graft onto the anarchism of a previous era – in the manner of libertarian Marxism or the post-1968 New Left – but purely and simply as a projection onto the tolerant and unfenced space of anarchism of the staple fare of academic postmodern revisionism, whose dual feature is to be as indifferent to questions of social emancipation as it is infatuated with fluid identity”.

Gomez goes further still in suggesting that this postanarchism represents nothing less than an attempt to water down anarchism.

“The deconstruction mechanism consists of a dual movement of rupture and parasitism. On one hand, nothing is left standing of the former anarchist corpus, which is now seen as metaphysical, essentialist, positivist, scientistic, humanist, and, above all, obsolescent. On the other hand, the name is reappropriated, in prefixed form, to complete its dilution by pseudomorphosis”.

On a political level, this means that anarchism is deprived of the very basis of its engagement in social struggle – it is not contemporary capitalist society that is primarily deconstructed by the theorists, but the meaning and purpose of our revolt against it.

As Harlou points out, in characterising the future society imagined by anarchist revolutionaries as just another potential norm imposed on individuals, the Foucaultians show themselves to be “frankly reactionary, in the sense of counter-revolutionary”.

He quotes Garcia’s book in this respect: “The theme of deconstruction, rendered politically fertile by Foucault but present throughout the work of what is known in the USA as French Theory, leads to the condemnation of any attempted criticism seeking to guide the political and social struggle according to notions such as human dignity, justice or truth.

“Drawing up a vision of what society could look like without capitalism and of the ways in which, in such a society, we could be human in different and better ways, is something that seems to make less and less sense within the very milieus which claim to offer a critical diagnosis of contemporary society”.

Gomez cites David Graeber’s comment (in Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of our Own Dreams) that the postmodern approach ultimately leads to the quietist argument that “resistance is futile (or at least, that organized political resistance is futile), that power is simply the basic constituent of everything, and often enough, that there is no way out of a totalizing system, and that we should just learn to accept it with a certain ironic detachment”.

In that same book, Graeber goes on to outline the ways in which postmodernism fits in very nicely with the world-view of contemporary global capitalism or neoliberalism.

He roughly summaries the postmodern arguments as:

“1. We now live in a Postmodern Age. The world has changed; no one is responsible, it simply happened as a result of inexorable processes; neither can we do anything about it, but we must simply adopt ourselves to new conditions.

2. One result of our postmodern condition is that schemes to change the world or human society through collective political action are no longer viable. Everything is broken up and fragmented; anyway, such schemes will inevitably either prove impossible, or produce totalitarian nightmares.

3. While this might seem to leave little room for human agency in history, one need not despair completely. Legitimate political action can take place, provided it is on a personal level: through the fashioning of subversive identities, forms of creative consumption, and the like. Such action is itself political and potentially liberatory”.

And he then goes on to summarise the viewpoint of global capitalism:

“1. We now live in the age of the Global Market. The world has changed; no one is responsible, it simply happened as the result of inexorable processes; neither can we do anything about it, but we must simply adopt ourselves to new conditions.

2. One result is that schemes aiming to change society through collective political action are no longer viable. Dreams of revolution have been proven impossible or, worse, bound to produce totalitarian nightmares; even any idea of changing society through electoral politics must now be abandoned in the name of ‘competitiveness’.

3. If this might seem to leave little room for democracy, one need not despair: market behavior, and particularly individual consumption decisions, are democracy; indeed, they are all the democracy we’ll ever really need”.

The parallels are clear – and the onus is on the anarchist proponents of postmodernism to demonstrate the ways in which their philosophy essentially differs from contemporary liberal capitalist orthodoxy.

Well said. I have been waiting for a good critique of post-modernism and deconstruction.

looking forward to a more articulated article, very nice.

some bits of Re-enchanting humanity by Bookchin could be useful.

Bookchin, M., 1995. Re-enchanting humanity. London: Cassell.