Michael Paraskos, Herbert Read: Art and Idealism (Mitcham: The Orage Press, 2014)

Much of the overall decline of our collective intellectual culture involves the breaking-down of things into constituent parts.

Detail is studied at the expense of any overview and discussion often centres around which label or classification can be applied to an idea or a thinker, rather than on their actual content or significance.

Anarchism can present problems for those who operate within that mindset, as it reaches deeper than the superficial level of other “political” ideas – it provokes with paradox, combines apparently contradictory concepts at higher levels of abstraction and refuses to be contained by the assumptions of one-dimensional theorising.

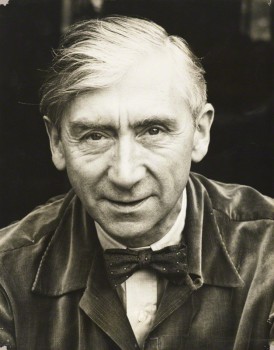

The great 20th century English anarchist Herbert Read was an excellent example of the multi-dimensional complexity of the anarchist mind, which is perhaps why he today does not always receive the recognition he deserves, despite his unusual record of having been a towering figure of the modern art world and also a vocal advocate of anarchism.

Happily, this neglect is now showing signs of being remedied. Following the release of Huw Wahl’s fascinating documentary film To Hell With Culture, The Orage Press has published a study of Read by Dr Michael Paraskos.

Herbert Read: Art and Idealism makes no futile attempt to flatten out Read’s work and life in order to make it fit into some pre-determined category.

Instead, Paraskos skilfully shows the interweaving threads of Read’s artistic and anarchist positions, demonstrating how his approach to thought was itself a part of his philosophy.

He writes: “Read’s tendency was always to synthesise ideas from diverse sources, hybridising them into new forms, some of which the authors of his original material would undoubtedly have rejected… Read began to develop a theory of culture that was re-integrationist or synthesist”.

In the field of art criticism, Read worked to transcend the false polarity between classicism and romanticism, which manifested itself at the time as the divide between, respectively, Constructivism and Surrealism.

By championing both movements, he inevitably also partly alienated each of them, but this did not deter him from his creative approach.

Read’s non-aligned position was not the result of indecision, or of some desire for middle-of-the-road compromise, but for a synthesis that transcended a superficial division.

It was this same seeking-out of higher levels of understanding that enabled him to embrace modern art while despising modern industrial civilisation, or to draw inspiration from both John Ruskin and Friedrich Nietzsche.

This attitude also informed his own version of existentialist thought, as Paraskos explains: “Read suggested that like all humanity the existentialists stood on the edge of an abyss facing the truth of their own insignificance. Whereas most of humanity was oblivious of the abyss, the existentialists recognised their situation and were overwhelmed by Angst.

“But for Read there was not a simple choice between ignorance of the abyss and Angst-ridden knowledge of it. As with his attempt to unify classicism and romanticism, Read synthesised a third response. He suggested that standing at the edge of the abyss was another group of people who saw their true situation as well as any existentialist. But instead of being overwhelmed by Angst, this group possessed a fascination with both the interior mental world and the exterior material world of apparent existence. According to Read, such people were like Aristotle, and were filled with interest, excitement and wonder.”

This Readian existentialism amounted to the message that “the transformation of society depended on an absolute individuality based on absolute responsibility for one’s own actions” – the core of the anarchist philosophy of resistance.

Paraskos stresses that Read’s thinking about art and philosophy cannot be separated from his anarchism and that he was involved in “an attempt to reconcile the material, or we might say physical, philosophy of anarchism with the seemingly immaterial, or metaphysical, philosophy of idealism”.

The importance of this task remains acute today, when too many anarchists fail to understand the ways in which their philosophy reaches out beyond mere political theory towards an holistic metaphysics.

The idea of inherent form, which fascinated Read and which links in with his interest in Jungian theory of archetypes, is a bedrock of coherent anarchist philosophy and yet seems to be little appreciated.

It was in the nature of Read’s philosophical journey that it would never – could never – be completed. But if 21st century anarchists care to take the time to study his journey, and contemplate his approach, they may well discover the urge to step off the well-trod road of narrow thinking and forge their own path of empowering intellectual discovery. This book is a very welcome and pertinent encouragement of that process.

Leave a Reply