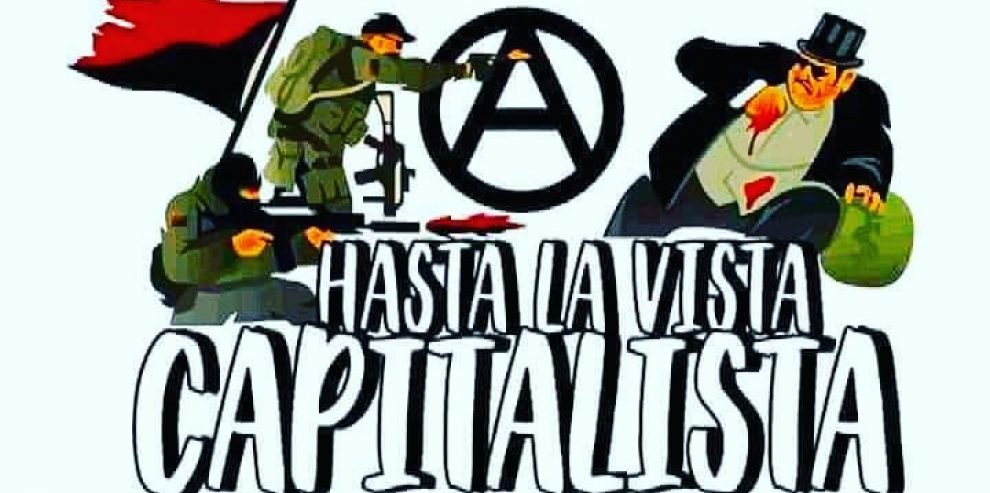

This piece is intended to tease out the relationship between revolutionary anarchism and identity politics in the Irish context.

Identity politics will be synopsis-ed here as a set of political positions which aims to place feminist and intersectional politics as being of central importance within anarchist discourse and usually emphasising their equal importance to class politics.

Identity can be roughly defined as a repeated set of behaviours and cultural norms an individual(s) carries out in their daily life. This means that being working class, as well as being a material position in capitalist society, is also an identity. To call yourself ”working class” is automatically recognising the existence of identity politics, and placing yourself within that arena.

Similarly Irish republicans, or Irish anti-imperialists, recognise that identity, and the related ”Irish” identity politics, is of upmost importance when asserting their right to an Irish identity in the face of British occupation. In Ireland this takes many forms, from commemorations and parades held without asking for permission from either the British state or the Free state, up to and including armed resistance against the occupation to assert an Irish identity and an Irish republican one at that, in the face of harsh repression.

Suffice to say, that on the island of Ireland, identity politics is integral to all strands of revolutionary thought and practice.But how does it intersect with Irish Anarchist politics?

Traditionally Irish anarchists have placed enormous emphasis on working class identity and struggle, importing it from European strands of socialism and anarchism as almost the holy grail to revolutionary thinking and action. A revolutionary group or individual that did not have a strong, pro-active and positive position on trade union struggle for instance would be scorned for being ”ultra left” or even completely ignored for failing to recognise the central truth that is, ”working class” struggle–the great, main contradiction which holds the potential to rupture all of capitalist society leading to the birth of a new egalitarian one.

But is it really so?

Over 100 years ago during the Land war when economic warfare and struggle was widespread in Ireland, or in Spain, Italy or Germany during the 1st third of the last century when insurrections stemming from protests over food prices and working conditions could be ignited with a few well placed revolutionaries, maybe, but not today, especially not in Ireland.

In fairness most Irish Anarchists have added on many identities, moving away from class struggle reductionalism, while maintaining class identity centrality. However this has been done without almost any analysis as to who are potential revolutionary agents and where potential revolutionary activity lies identifying who in society may be a potential revolutionary agent was, originally, one of the main aims of left wing intellectual debate and scrutiny. From this debate then, action could be organised around points of conflict within society around certain identities.

Marxists and anarcho-syndicalists placed emphasis on the working class as a whole to be the revolutionary agents, where the point of focus of conflict would be the workplace and economic struggle. Bakunin and his followers were more sceptical believing that those at the bottom of society and outside the traditional working class, the peasantry, bandits ect were more fertile groups for revolutionary activity. This difference of emphasis lay mainly in a differing view of revolution.Bakuninists, so to speak, viewed the revolution to be a destructive process and as anarchists, were sceptical of large scale formal organisations which may become organs of repression in the future. The Marxists and syndicalists viewed revolution to be less destructive with more tutelage from existing or newly created formal structures which would ease their way into a new world. At time and after Bakunin anarchists very cautiously made their way into unions in order to ferment rebellion and strike action through them. Wary at all times, even then, of their reformist and often conservative nature.

In todays Ireland strike action is out. A total of 10 industrial disputes were in progress during 2018 – involving only 1,800 workers. A revolution waiting to happen? hardly.

They were in areas from finance and real estate to transport and storage.

New CSO figures show it cost the state 4,050 days – the lowest level of disruption in 7 years.

Even with high profile strikes such as by nurses, there is no room for escalation or militancy. Union action is dead. Traditional working class action has been neutralised through social partnership, atomisation and the power of the bosses.So back to the main question, if working class as an identity no longer holds the key potential to rupturing capitalist society were does it lie in Ireland?

Womens struggle?Lgbt struggle? Unfortunately it is the opinion of the author that these can all be easily coopted into capitalism and utilised for maintaining capitalist normality. That is not to say we should all be assholes to each other in any way. Just that these movements do not offer scope for radical change.The repeal and marriage campaigns are probably the best example of this. Brought to the fore by a right wing government and utilised to create a shiny new Leo Vradakar brand of blue shirts these movements have little in reality to do with rupturing state capitalist society, or building the ability to do so.

So were is that potential now?

The environmental struggle is one of the most widespread and unfought issues alive today. Everyone talks about it but does nothing. It also contains the widest potential for direct action and militancy. The Shannon lng project, The Sperrins mining project, fracking north and south and numerous other small and intermediate projects which are open to sabotage and blockading. It is a campaign that goes to the heart of the structures of maximal profit capitalism. Radical anti-capitalism, direct action and environmentalism go hand in hand.

Anti-imperialism as a tenet of all struggle.

Ireland remains partly occupied up north and down south a gombeen counter revolutionary statelet remains in power. To maintain these states the most draconian laws in europe have been brought in under anti terror legislation, stronger down south than up north. Anti-imperialist campaigns, tied in with environmental anti capitalist campaigns could be built. A movement against International foreign multinationals coming to this country to take its resources, facilitated by an occupying imperialist state and its gombeen statelet down south could easily strike a cord with the Irish physce. These foreign multinationals are also plundering our housing resources, driving up house and rent prices.

Housing.

While the scope for a national campaign here is smaller a campaign of direct action against multinational corporations, who have been employing imperialist loyalists paramiliatries down south for evictions could be tied in with and overall anti-imperialist and ecological anti capitalist movement. None of these things would be easy and all of them would mean a major strategic shift for anarchists in Ireland.

One thing the reader may have noticed from these conclusions is that it is not the identity that is associated with a particular campaign or individual that is important but the qualitative nature of the campaign activity, whether it is militant or reformist. An individual identifying as being a queer woman, for instance, may be involved in a militant housing, anti-imperialist or ecological action, it is not the specific identity of the individual that is important from an anarchist perspective but the militancy and therefore effectiveness of the action.

From this perspective action should unite us, and identity enlighten us to each others backgrounds, therefore building affinity and solidarity between us as comrades.