Guest Analysis: An Antifascist Perspective on Digital Censorship of Far Right Extremists

FOREWORD: The following article has been submitted by a guest writer who is interested in researching social disinformation, the nature of truth and disparate realities, and how communication platforms have affected that. Accompanying images are sourced by ARC.

If you would like to have something published on our blog, please send us an email.

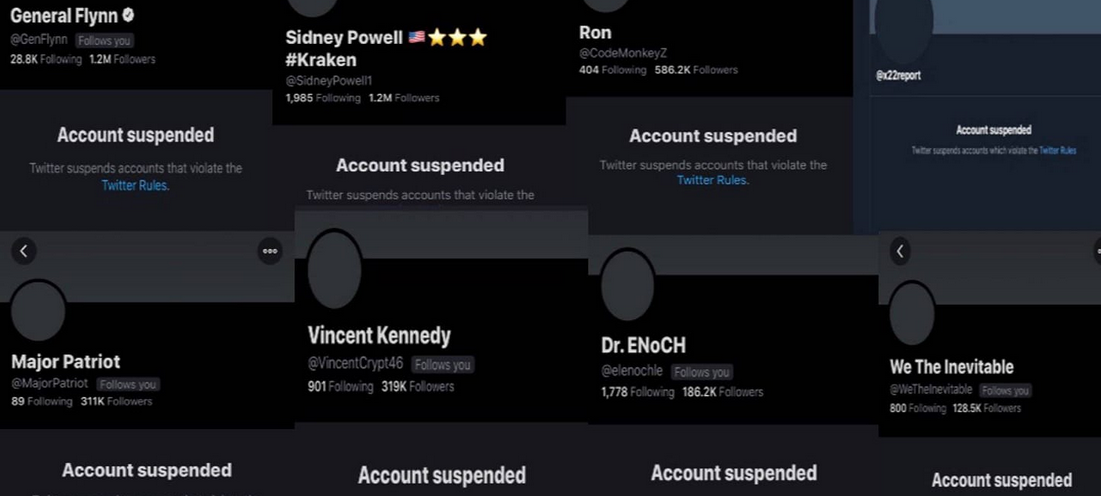

With the January 6th storming of Capitol Hill and subsequent clampdown by major social media platforms on far-right speech, questions about how the far-right organise have become prominent in the mainstream, both in the U.S. and the U.K. It has even gone so far as constituting a major feature during the BBC’s Newsnight, with Emily Maitlis asking on January 11th whether banning far-right talking points such as #StopTheSteal (as Facebook has done) and shutting down sites such as Parler (as Amazon Web Services have done) might only drive right-wing extremists underground. It is important that these questions are not answered incorrectly, or that mainstream narratives are led astray by misinformation and a lack of understanding. That’s why we feel it is important to address this as a group well-placed to do so. It is important to recognise that there are other issues at play here – is it right for such a small group of corporations, often controlled by one or two major shareholders to have the power to cut off a U.S. President from much of his audience? These questions are important but outside of the scope of this article. Here, we want to address only the effects on the far-right and their ability to organise.

The first thing to be said is that far-right extremists will always find ways to organise. Whether they are allowed to proselytise and radicalise on Twitter and Facebook or not, there will always be a hardcore who find themselves on sites which allow far more extreme views, such as 8kun. Whether are not they are allowed to organise and plan in plain view, the smart ones will still use encrypted messaging apps such as Signal, encrypted email, or the dark web. In short, they will always find somewhere to hide and there is next to nothing that can be done about this. Anything that could be done to curb this level of organisation is only going to harm legitimate users of privacy-focused platforms more – for every Nazi you hinder by shutting down a covert platform, you’re going to hinder many more genuine activists working for a better world, journalists in danger from their government, or whistle-blowers who fear for their lives and livelihoods. A good example of this is the encrypted messaging and broadcasting app, Telegram. Telegram is used by activists across the political spectrum. The saving grace of Telegram is that despite being encrypted, many chats are open and easy to access, making monitoring easier – along with private group chats like you might find on a more traditional encrypted messaging app like Signal, Telegram hosts massive open chats, a sort of fast-fire forum. This means that, while Telegram absolutely is a fertile breeding ground for the far-right, it can also generally be watched by those aiming to counter far-right narratives and activities. The damage done to legitimate movements if we lost Telegram entirely could be catastrophic. Along with this we must also acknowledge that you will never get rid of the far-right entirely. There will always be someone with hateful ideas trying to spread them.

With that in mind, what is the goal? Far-right extremists rely on two things. Firstly, they need their message to get out to as many people as possible. The more people the message goes out to, the more people vulnerable to their invective they’ll be able to bring on board. If a Nazi screams themself raw in a forest and no one’s there to hear it, does it really make a sound? By limiting their audience, we limit the number of people exposed to far-right ideas, limiting the number of people who fall under the extremists’ sway, and hence hamper their ability to grow into a threatening movement. In the case of the Capitol attack, right-wing activists had been funnelled for years from platforms like Twitter and Facebook onto more and more extreme websites such as Parler, thedonald.win, 8kun (formerly 8chan), and Stormfront. If those people had never been exposed to the blunt end of the stick on mainstream sites, they would likely never have ended up being radicalised at the sharp end.

There’s the argument that if these ideas are out in the open, they can be challenged, but what does that look like? A bunch of well-meaning liberal-minded people on Twitter piling onto a far-right extremist does not challenge the extremist. It gives them a greater platform. No one has ever been turned away from extremism by the bite-sized arguments of internet strangers. The kind of people who are preyed on by the far-right are generally not predisposed to siding with the ‘liberal Twitterati’ anyway. On top of that, the kind of debates that the far-right want to have are not the sort of questions a healthy society should be asking – they’re the sort of questions that would be long settled if not for a few hateful figures being able to spread their ideology by bringing up the same topics again and again. This is also why de-platforming the far-right is generally an effective tactic.

Secondly, they need their rhetoric to become more and more normalised. A moderate right-winger might, ten years ago, have balked at the idea of some of the things said and done by Trump and his supporters in the past few years but as Trump and the far-right were allowed to push increasingly extreme right-wing ideas into the mainstream, those ideas gradually became more palatable to a wider number of people. In the last paragraph the idea of some people being more vulnerable to this form of extreme radicalisation was brought up – the effect of normalising far-right ideas is that more and more people become more vulnerable. These views appearing specifically on mainstream sites means that they are not only seen and ingested by more people, but that more people are likely to take them seriously and go down the rabbit hole because these views suddenly seem more rational and acceptable – after all, if they were that crazy and extreme, they wouldn’t be on Twitter, right?

This is why it is undoubtedly a good thing for Facebook, Twitter and other mainstream platforms to severely limit the far-right on their platforms. It stops them reaching people, it stops their rhetoric going mainstream, and it stops their hateful movements from growing to the sort of critical mass that results in the US Capitol being stormed by a crowd of baying fascists. It also drives down the incidence of isolated attacks by lone wolf extremists.

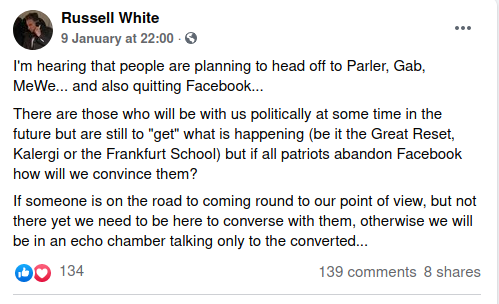

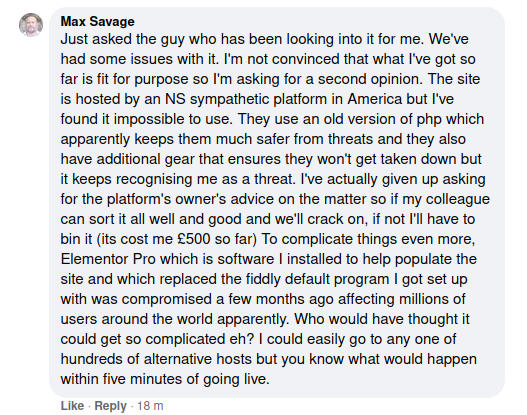

What about sites like Parler and Gab? They sit in a strange middle-ground, somewhere between the Facebooks and the 8kuns. Does taking down the likes of Parler really hinder the growth of hateful movements? Yes. The average person involved in the far-right is not a die hard extremist. The die hard extremists will always find a way to organise so we discount the effect on them – in all likelihood they’re already on the most extreme, underground platforms available. We’re worried about the people at the more moderate end of the Parler spectrum (who, to be clear, are not moderate at all when taken out of the context of Parler). Removing Parler will result in some proportion of these people simply dropping out of online far-right spaces. Unfortunately due to the highly addictive nature of social media in general, this number will not be as high as we’d like, but it’s there. Removing Parler also takes away another veneer of normality and acceptability from the far-right. It’s easy to transition to a site like Gab or Parler, because in terms of their user interface and graphics, they actually look pretty much like normal, mainstream websites. They look acceptable. They aren’t difficult to use. They have a comfortable familiarity which makes it all the easier to get sucked in. The natural places for those who choose to stay in online communities after the likes of Parler and Gab go, such as 8kun, Stormfront, and thedonald.win do not. They’re awkward and clunky, and don’t have the same dopamine-inducing mechanics as their more mainstream cousins. They’re off-putting to the technologically un-savvy, far more esoteric and strange. They do not have that veneer of legitimacy. This is important for the reasons stated above.

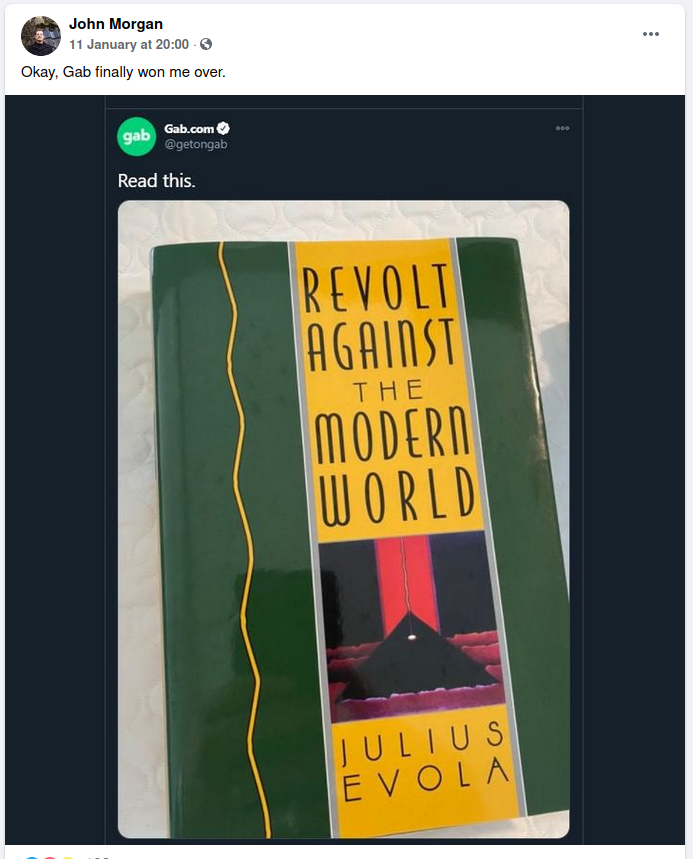

It’s not all rosy, however. The most worrying consequence of Parler going dark is the migration to Gab, which is already confirmed to be happening. At some points over the past week, Gab has reported up 10,000+ new users per hour. This is a concern because Gab tends to host more extreme opinions than Parler did, simply as a consequence of its user-base. Whereas Parler was more a home to civic nationalists, Gab is far more openly ethnonationalist. This could result in some already fairly extreme conservatives being radicalised even further by their new community. All in all I’d say this is probably a risk worth taking – if we’re to be scared off from shutting down extreme far-right platforms by risks like this, then there is little option but to allow them to proliferate. This is still very much an ongoing debate, however.

In conclusion, there is only so much that can be done to prevent the far-right from organising online. The hardcore will always manage. But in the meantime we can make it more difficult for them to recruit, and prevent them from normalising and legitimising their hateful ideas in the mainstream, by keeping their ideologies to the darkest, deepest, least friendly corners of the web. Corporate and state-implemented bans can only go so far, however, before infringing on the rights of normal citizens and activists, a more comprehensive, society-wide approach is needed.

Leave a Reply