By MG

I have been frustrated with the culture and lifestyle associated with activism for a long time. In the UK, where I live, a particular, narrow section of the community seems to have taken ownership of the term “activist” and used it to label and justify its own activities. It was my increasingly negative perception of the anarchist activist scene that I was a part of that led me to write Why I Hate Activism, criticising the white, middle class, patriarchal values that still ruled the roost in the “alternative” subculture. The article was published on the Ceasefire magazine site but was subsequently reposted on various other activist sites and blogs.

I should say from the start that I have been deeply involved in activism for many years and have to take responsibility for my own complicity in its failings. If it hadn’t been for good friends who shared their experiences of exclusion and alienation I might never have noticed the fundamental flaws of what I was involved in. I felt a responsibility to write about the new understanding that these shared experiences had given me, as a way of showing solidarity with the excluded and to raise awareness about the power dynamics that I felt were often made invisible. Because I felt passionately about what I was writing, I was angry and antagonistic and was not always receptive to the often helpful comments others were making about the piece. Having stepped back and reflected more on the conversations that began, I’d like to try to engage in them more constructively than before.

Initial responses to the article were quite polarised with some readers seeing aspects of their own experiences touched on whilst others felt that my article was inappropriate. Given the many criticisms, I felt the need to clear up misconceptions, take heed of others’ personal experiences and try to make some positive suggestions about what we can do.

Firstly, I want to make clear what I think is the problem and why it definitely should be viewed as a problem by anyone who is against hierarchical systems. I think that the activist scene reproduces many of the hierarchies of visibility and privilege present in mainstream society and that this is not being challenged. In particular, white British cultural norms, especially those of the middle classes, are privileged within the scene. This has given particular privileged people the feeling of ownership over the term activism, which has come to describe a movement in which they are guaranteed a place. It subsequently marginalises those activists whose activities and identities do not fit the cultural norm.

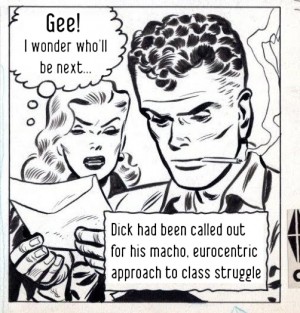

Many of the events and campaigns that come from the self-defining activist community reflect the preconceptions and preoccupations of this elite group. Attempts to challenge privilege are usually treated as subordinate to saving the planet/helping refugees/attacking capital, etc and are not taken too seriously. Fighting the state and capitalism are given priority over struggling against hierarchies which white, middle class men benefit from. When privilege is challenged more effectively, a smokescreen of denial goes up, obscuring the real issues until the threat has passed. Take, for instance, the anarchafeminist intervention at the UK Anarchist Movement Conference which was subsequently ridiculed by some activist men as “retrograde” (because the women involved masked their faces), “pathetic” and “manipulative”. The privileged activists lined up to belittle the action with no apparent awareness of how they were being dominating, disempowering and misogynist. The attitude amongst many of these self-appointed leaders seems to be one of outrage that women, people of colour, queers and disabled people should challenge their authority.

Faced with this cultural hegemony, many of those who don’t feel that they fit in rapidly become disillusioned with the scene and move on to environments where their race, class, sexuality and gender aren’t reasons for their exclusion or exploitation. The result is described by Kareem, who commented on the original article:

Speaking simply from experience, it is not easy for someone with a background in the Global South, especially if they also come from a working class (or even lower middle class) background, to adjust to a lifestyle and become accepted within the activist communities referred to in the piece. This is not to valorise either black and brown people, or people from a non-elite class background, except to say that if such people feel automatically alienated from activist groups – and I think many do – it is difficult to think of how such groups will bring about lasting, progressive social change.

This conclusion was echoed by Elena, who recalled her experiences of leftist activism at university as being “a very macho environment in which I felt very uncomfortable. Unfortunately it can only take a few bad experiences when someone is first dipping their toe in the water to put a curious progressive person off for life.” Switch commented that the “mainstream” activist movement “makes it look like there is one ‘movement,’ which perpetuates the invisibility of parallel movements in other (non-white, non-punk, non-student) subcultures…, but there are of course much purer revolutionary elements in all sorts of places).”

But whilst these people’s experiences seemed to validate my observations, there were many criticisms of what I had written. For example, Sara claimed that: “[t]he polemic has its uses sure, but how useful is it against potential allies; how productive is it?” She continued:

Representational polemic… disarms and is disempowering; it speaks over, speaks at as opposed to engaging with and opening up a conversation, a dialogue in which all parties are vulnerable and put themselves on the line, and learn to trust each other to be able to begin to deal with the difficult complicities and contradictions in many of our political actions and relationships amongst ourselves and the wider community.

I think that this is certainly true of the ways in which I and other university-educated people learn to engage with these problems. By adopting a particular form and style of writing to express our discontent we perpetuate an exclusionary mode of communication. However, given that the piece was aimed at precisely the kind of people who communicate in this way, I would argue that it was not excluding its targets from engaging in conversation.

I would like to move towards a place where we can sit down together, in mutual trust, to discuss as equals. But given the hierarchies that exist within the activist community this isn’t possible at the moment. There isn’t the willingness to engage with these issues because many activists don’t realise there is a problem. I think there’s an urgent need to communicate that there are very serious problems in how we relate to one another. Until privileges are meticulously unpicked, I think it’s unwise to expect genuine dialogue (as opposed to power games) to emerge.

Other commenters seemed to disagree that the cultural majority should have to change. Andy argued that:

If people feel existing activism does not resonate with their particular ethnic or class culture, maybe instead of complaining about others living their own way (which after all, isn’t doing you any harm and very often is also socially taboo or dissident), these people should form their own affinity-groups with people who share their culture, and network these affinity-groups into the network.

These sentiments, to me, betray a lack of understanding of the problems faced by those without access to the existing activist scene. The people Andy seemed to have in mind could (and often do) form groups with people who share their culture (when they can, and often they can’t which is why they turn to the wider activist community in the first place), but then they face invisibility or reduced visibility in the wider activist scene. They may be assumed to be focussed on identity politics or accused of being separatist, even though they may feel that they should be included in wider activist circles. The decision to form culturally specific groups often results in reduced trust from the wider network, as the in-group, paradoxically, feels excluded by the autonomy of those with different cultural values. Certainly, a minority group that chooses to organise in this way may feel more autonomy, but this may come at the expense of increased separation. To blame the excludeds’ own cultural practices for their separation demonstrates a lack of appreciation of the power dynamics at play, where the majority’s cultural practices are assumed to be the norm.

Whilst I want to continue to engage in conversation with other activists and those who would be activists about the precise nature of the problems, I also feel like I should offer some suggestions about how we might start remedying the situation. For me, the main problems are the power differentials that exist within wider society and that inevitably contaminate any activist groupings we create. I think that we need to work to identify and eliminate male privilege, white supremacy, heteronormativity and other hierarchical modes of thinking not just in the obvious baddies (the police, the fascists, etc.) but in ourselves. We need to make effort to educate ourselves through the experiences of those who have suffered from and have been complicit in the kinds of abuses we seek to eliminate. There is a wealth of information available in zines, books and on the internet that is relevant to the issues I am talking about. We need to make ourselves, our friends and accomplices aware of these viewpoints. When we experience resistance to the ideas that we find, we should interrogate that resistance and try to work out whether we have vested interests in maintaining hierarchies. I have found groups such as pro-feminist men’s groups invaluable for creating spaces conducive to collective unpicking of our complicity in perpetuating hierarchies. Many people write off such ventures as hand-wringing guilt-fests but I have found them to be a necessary step in taking collective responsibility to change the values that exist in activist spaces.

I think that once tribal groups (e.g. men, white people, straight people) have made an effort to empathise with the experiences of others and people are taking responsibility as individuals and as part of wider collectives to combat hierarchy formation and perpetuation, dialogue can begin in earnest. Once there is a respect for others’ views and perspectives we can begin a conversation. We can start to share our vulnerabilities with one another, as those afraid of being dominated and those afraid of losing our privilege. Once people recognise the divides that exist and make genuine efforts to move beyond them, trust becomes a possibility.

I am excited at the prospect of reaching this stage in the communities I am involved with although, of course, it is a daunting mountain to climb, personally and collectively. I think that, by incorporating a lifelong struggle against our own conditioned value systems into our actions, we can move towards more enriching and sustainable relationships. It is in everybody’s interests that we work to accomplish this.

<<<<<<this is not an exhaustive list.

<<<<<<this is not an exhaustive list.