A good read for anyone who understands French is Lèse Beton, a bulletin from the ZAD occupation against a new airport near Nantes.

It’s subtitled “against the airport and the world that goes with it” and it’s this sense of perspective that appeals to me.

One particular article in the summer 2013 edition explains that Nantes has been named “green capital” of the year – and is reminding its residents of the fact through endless billboards.

It asks how this title was ever bestowed on a town “with ambitions to expand as far as Saint-Nazaire, which is widening its roads and is so eager to push through its airport project”.

The answer, it seems, lies in its glossy presentation skills and a marketing angle presenting Nantes as a hub for the “Grand Ouest”, a centre of good living that appeals to the “creative classes”, by which they mean executives, professionals, people with loads of money to spend.

All the big cities, metropolises and regions are now in competition with each other to draw in wealth, the article notes. “The principal objective of a town becomes the same as that of a business – competivitity”.

It adds that the modern metropolis also includes a space around it for agriculture, a green belt featuring the odd park or nature reserve. “Because they need little bits of green somewhere for them to concrete around.”

Behind all this is “a global logic in which the only criterion for judging a project is economic profit”, says the article.

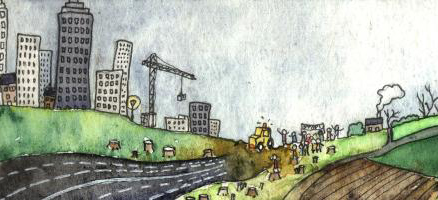

It continues: “Anything which isn’t actually within the metropolis is considered to be there to serve the metropolis. Since, according to the Journal de Nantes Métropole, ‘the attractiveness of a town is measured by the number of its connections it establishes with the rest of the world’, the countryside gets gobbled up by the transport infrastructure linking urban nodes: coastal motorways, high-voltage power lines, pipelines, and of course, here in Nantes, a grandiose international airport.

“The priority is increasing the flow of energy and information, accelerating the movement of goods and members of the ruling classes. With rationalisation comes the suffocation, isolation and destruction of the smallest pockets of autonomy. Space is arranged to exclude anything beyond the officially-defined purpose and laced with CCTV, cops and consultants.

“Unexpected encounters, street life and makeshift areas have no place there. Life in the metropolis is about travelling from one designated space to another: from the place of work to the place of consumption; passing through a district on your way home to a dormitory zone in the town or surrounding village.

“Life in a metropolis is to be forever on the move in functional zones. The construction of this metropolis always involves tearing people away from their spaces, their soil, their neighbourhood, their connections.

“We don’t want our space organised in a way that revolves around financial returns, where the bosses decide whether to pull down or put up according to their idea of how things should be arranged.

“We don’t want isolated lives in sleek, compartmentalized spaces. We want to live in our neighbourhoods or countryside. We want to co-operate with the people we share our space with. We want to choose together what we do there, and how we do it, according to our own needs. We want friendships, we want to meet people. We want to have control over our own lives.”

Leave a Reply