There is something about the mainstream Marxist “Left” that turns the stomach of many an anarchist.

It’s not simply the blinkered obsession with “organising in the workplace”, the permanent party recruitment drives, the endless time-wasting loop of electoral hope and disappointment, or the depressing and disempowering officially-authorised and heavily-stewarded marches that culminate in the inevitable tedium of the same old faces delivering the same old pointless speeches.

There is something else, something even greater than the sum of all these, which pollutes the very atmosphere of this pseudo-radical sub-culture. And this “something” is essentially a “nothing”, an absence or void which sucks into it all the superficially good intent of the politicking around it.

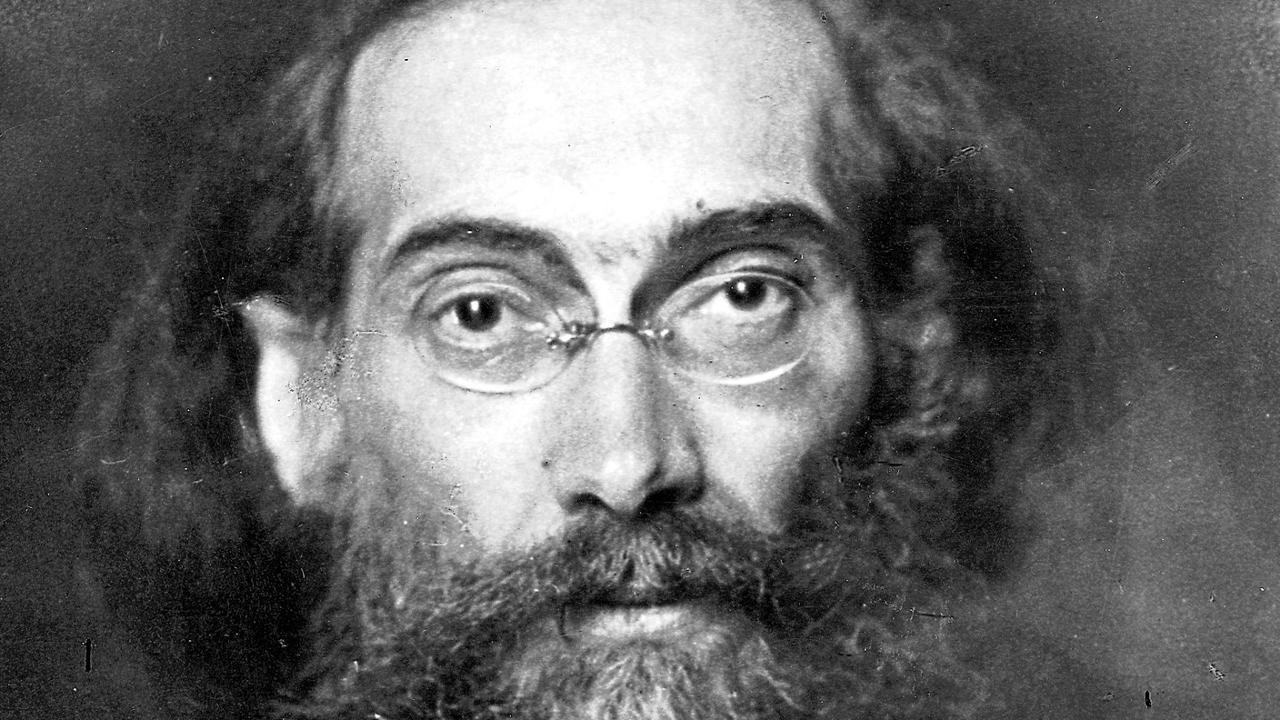

One anarchist who brilliantly described this phenomenon was Gustav Landauer. And the fact that he did so 100 years ago goes to show that there is nothing new or passing about the failings of the Left.

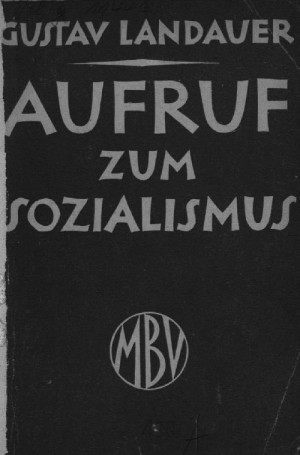

In his brilliant booklet For Socialism, (which he updated just before he was murdered by proto-fascists in 1919) he contrasted his own anarchist-socialism with the Marxist version.

This ideological broadside was born specifically out of his frustration with the Social Democratic Party in Germany, but his criticism of Marxist ideology itself went much deeper and is every bit as relevant today.

Landauer said that by insisting that socialism can only result from the rise and fall of capitalism, Marxism had declared itself dependent on capitalism, rather than a completely opposing tendency.

It even shared the capitalist mindset of regarding human life and relationships in purely mechanical terms.

He rejected the “the grotesque wrongness of their materialist conception of history” in which Marxists reduced everything to “what they call economic and social reality”.

For Landauer, greater and much more powerful factors were at work in society, on which he rested his hopes of revolution. He wrote constantly about the existence of Geist, or spirit, as the force capable of inspiring a revolt with the necessary vitality and resonance to overthrow the capitalist order.

But this element of human culture had no place in Marxism, which Landauer condemned as “a negating, destructive and crippling appeal to impotence, lack of will, surrender and indifference”.

He noted: “The Marxists have, in their declarations and views, excluded the spirit for a very natural, indeed almost excellent material reason: namely, because they have no spirit”.

Landauer was, of course, far from the only anarchist to have criticised the Left on these grounds.

Bakunin, for instance, described a number of “natural traits” ignored by Marxist theory, including “the intensity of the instinct of revolt, and by the same token, of liberty, with which it is endowed or which it has conserved. This instinct is a fact which is completely primordial and animal; one finds it in different degrees in every living being, and the energy, the vital power of each is to be measured by its intensity”.

Emma Goldman, too, described her first impressions of Marxism as “colourless and mechanistic”, in stark contrast to the “beautiful ideal” of anarchism to which she dedicated her life.

But, unfortunately, this hasn’t stopped anarchists from making the same mistakes and, by mimicking Marxist approaches, undermining the vital spirit which historically inspires anarchism.

It seems this process was already happening in Landauer’s day – he refers disparagingly to “the syndicalists and the anarcho-socialists, recently so-called by a pitiful misuse of two noble names” as the Marxists’ “brothers” and specifically extends his condemnation to all Marxists “whether they call themselves Social Democrats or anarchists”.

Since then, with the rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia and the 20th century predominance of Marxist ideas in anti-capitalist thought, the problem has probably got worse.

We have all encountered quasi-anarchists who shy away from labelling themselves as such, who are keen to disassociate themselves from “illegal” revolutionary activity, who insist on constraining and confining the scope of anarchist thought within the narrow boxes they have drawn for it.

At the same time there have been, and always will be, anarchists who feel in their blood that their beliefs are infinitely wider and deeper than such limited outlooks can ever concede.

The Russian anarchist Voline and other comrades, for instance, had this to say in response to the Organisational Platform of the Libertarian Communists, written by the Dielo Truda group of Russian exiles in 1926: “To maintain that anarchism is only a theory of classes is to limit it to a single viewpoint. Anarchism is more complex and pluralistic, like life itself.

“Its class element is above all its means of fighting for liberation; its humanitarian character is its ethical aspect, the foundation of society; its individualism is the goal of mankind”.

A quarter of a century after the collapse of the Soviet Union, there are signs that Marxism’s grip on global anti-capitalist thinking is finally loosening.

Now is the perfect time for anarchists to shake ourselves free of its deadening influence, distance ourselves from the tired reformist rhetoric of the political Left and rekindle the revolutionary fire of the timeless anarchist spirit once embraced by the likes of Bakunin, Goldman and Landauer.

Adapted from The Stifled Soul of Humankind

I picked up a leaflet from the Marxist Student Federation recently and was amazed to see that they thought education was a good idea because it helped “economic development”!! This is the sort of thinking you expect to hear from right-wing capitalists. Surely the whole point is that education is good in itself, in the same way that life is good in itself. Well, that’s the point for us anarchists anyway!