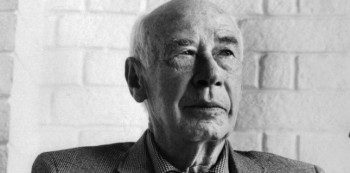

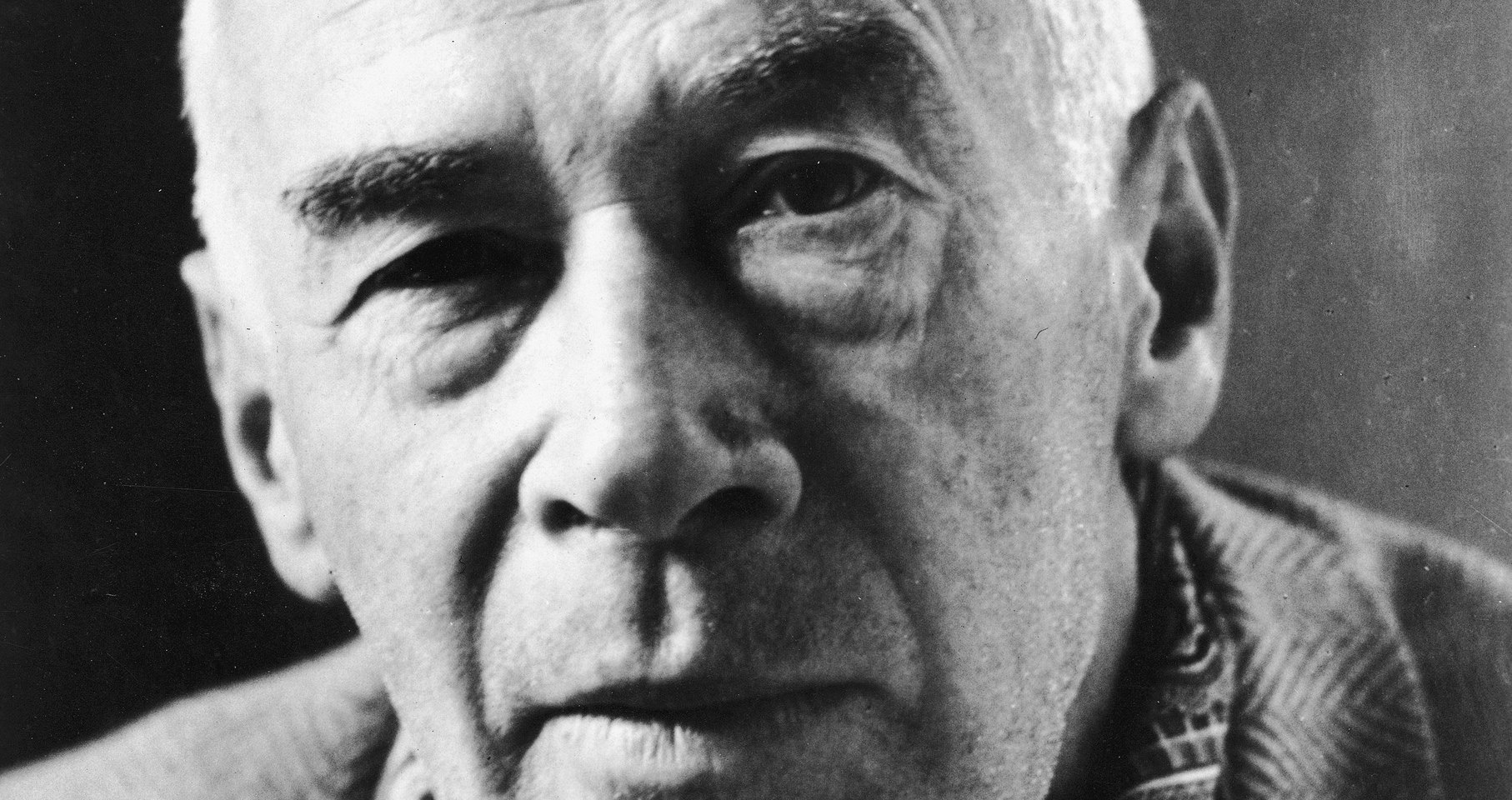

The American writer Henry Miller (1891-1980) is not primarily remembered as a critic of industrial civilization – he is better known, maybe, for his love affair with Anaïs Nin.

However, on many occasions he denounced the folly and debasement of the machine-age with unrivalled passion and articulacy.

And, behind the apparent negativity of his scathing and free-flowing wit, there shines forth a profound belief in the fundamental positivity of life as it is meant to be and could be for all of us if we only dared embrace it.

It perhaps the near-nihilism of some of Miller’s rants that initially catches the reader’s eye, such as this declaration in Tropic of Cancer, published in 1934: “For a hundred years or more the world, our world, has been dying. And not one man, in these last hundred years or so, has been crazy enough to put a bomb up the asshole of creation and set it off. The world is rotting away, dying piecemeal. But it needs the coup de grâce, it needs to be blown to smithereens”.

We see elsewhere that this fury against “the world” is rooted in an alienation that sets him apart from the rest, that makes him an outsider, who often feels he has little, if anything, in common with the vast majority of his contemporaries.

He writes in Tropic of Capricorn (1939): “What strikes me now as the most wonderful proof of my fitness, or unfitness, for the times is the fact that nothing people were writing or talking about had any real interest for me”.

The brunt of Miller’s disgust at modern society is often focused on his own country, America.

He describes New York, for instance, as “a whole city erected over a hollow pit of nothingness. Meaningless. Absolutely meaningless”. (Tropic of Cancer)

In Tropic of Capricorn he writes: “I think of all the streets in America combined as forming a huge cesspool, a cesspool of the spirit in which everything is sucked down and drained away to everlasting shit…

“I wanted to see America destroyed, razed from top to bottom. I wanted to see this happen purely out of vengeance, as atonement for the crimes that were committed against me and against others like me who have never been able to lift their voices and express their hatred, their rebellion, their legitimate blood lust”.

This criticism extends to a fear that America’s emptiness risks infecting the rest of the world. He notes while discussing India in Tropic of Cancer: “India’s enemy is not England, but America. India’s enemy is the time spirit, the hand which cannot be turned back. Nothing will avail to offset this virus which is poisoning the whole world. America is the very incarnation of doom. She will drag the whole world down to the bottomless pit”.

Miller’s pessimism about the direction of human civilization rivals that of Oswald Spengler (The Decline of the West) or René Guénon (The Crisis of the Modern World). He writes: “In the four hundred years since the last devouring soul appeared, the last man to know the meaning of ecstasy, there has been a constant and steady decline of man in art, in thought, in action. The world is pooped out: there isn’t a dry fart left. Who that has a desperate, hungry eye can have the slightest regard for these existent governments, laws, codes, principles, ideals, ideas, totems, and taboos?” (Tropic of Cancer)

And he makes it explicitly clear that his despair is directed at “that world which is peculiar to the big cities, the world of men and women whose last drop of juice has been squeezed out by the machine – the martyrs of modern progress”. (Tropic of Cancer p. 165)

In Tropic of Cancer he opens fire on the blind capitalist faith in “progress” through ever-increasing production: “The same story everywhere. If you want bread you’ve got to get in harness, get in lock step. Over all the earth a gray desert, a carpet of steel and cement. Production! More nuts and bolts, more barbed wire, more dog biscuits, more lawn mowers, more ball bearings, more high explosives, more tanks, more poison gas, more soap, more toothpaste, more newspapers, more education, more churches, more libraries, more museums. Forward!”

Miller’s criticism of the modern world is not conditional – he is not saying that it could be made better if only such and such a reform were carried out, if only such and such conditions were improved. It is the whole thing that he finds intolerable.

“The city itself strikes me as a piece of the highest insanity, everything about it, sewers, elevated lines, slot machines, newspapers, telephones, cops, doorknobs, flophouses, screens, toilet paper, everything. Everything could just as well not be and not only nothing lost but a whole universe gained. I look at the people brushing by me to see if by chance one of them might agree with me. Supposing I intercepted one of them and just asked him a simple question. Supposing I just said to him suddenly: ‘Why do you go on living the way you do?’ He would probably call a cop”. (Tropic of Capricorn)

It is not just the specific content of modernity that constitutes its baseness – an important consideration is the way it systematically destroys all that came before it and Miller was emotionally affected by the brutality with which this process flattened the living past out of the USA.

He writes in Tropic of Capricorn: “A European can scarcely know what this feeling is like. Even when a town becomes modernized, in Europe, there are still vestiges of the old. In America, though there are vestiges, they are effaced, wiped out of the consciousness, trampled upon, obliterated, nullified by the new. The new is, from day to day, a moth which eats into the fabric of life, leaving nothing finally but a great hole. Stanley and I, we were walking through this terrifying hole. Even a war does not bring this kind of desolation and destruction. Through war a town may be reduced to ashes and the entire population wiped out, but what springs up again resembles the old. Death is fecundating, for the soil as well as for the spirit. In America the destruction is complete, annihilating. There is no rebirth, only a cancerous growth, layer upon layer of new, poisonous tissue, each one uglier than the previous one”.

It is important to understand that Miller’s viewpoint is not a negative one. The same is true of anybody who criticises a particular state of affairs, no matter how vehemently. For behind a criticism of how things are, lies some sort of idea of how things should be.

The same is true for all critics of industrial civilization. We know the world we are living in just isn’t right. We may not be able to set out exactly what sort of world we do want to live in, or exactly how we would get there, but deep down within us there exists a positive notion of how things should and could be, which serves as the unconscious yardstick with which we measure and condemn the society in which we find ourselves trapped.

Miller hints at this idea when he writes that “only that interests me which I imagine to be, that which I had stifled every day in order to live” (Tropic of Capricorn) and again when he says: “There is only one thing which interests me vitally now, and that is the recording of all that which is omitted in books. Nobody, so far as I can see, is making use of those elements in the air which give direction and motivation to our lives”. (Tropic of Cancer)

Those “elements in the air”, directing our lives, are none other than the innate human aspirations towards freedom, co-operation, closeness to nature – all the inner tendencies that Miller sees “stifled every day” in modern society.

He actually takes the step of combining his criticism of modern society with his own vision of a free and anarchist non-industrial world in an remarkable and powerful passage in Tropic of Capricorn, worth citing in full:

“Why should I give a fuck about what anything costs? I’m here to live, not to calculate. And that’s just what the bastards don’t want you to do – to live! They want you to spend your whole life adding up figures. That makes sense to them. That’s reasonable. That’s intelligent. If I were running the boat, things wouldn’t be so orderly perhaps, but it would be gayer, by Jesus! You wouldn’t have to shit in your pants over trifles. Maybe there wouldn’t be macadamized roads and streamlined cars and loudspeakers and gadgets of a million billion varieties, maybe there wouldn’t even be glass in the windows, maybe you’d have to sleep on the ground, maybe there wouldn’t be French cooking and Italian cooking and Chinese cooking, maybe people would kill each other when their patience was exhausted and maybe nobody would stop them because there wouldn’t be any jails or any cops or judges, and there certainly wouldn’t be any cabinet ministers or legislatures because there wouldn’t be any goddamned laws to obey or disobey, and maybe it would take months and years to trek from place to place; but you wouldn’t need a visa or a passport or a carte d’identité because you wouldn’t be registered anywhere and you wouldn’t bear a number and if you wanted to change your name every week you could do it because it wouldn’t make any difference since you wouldn’t own anything except what you could carry around with you and why would you want to own anything when everything would be free?”

Miller, in the course of his own life, discovered that he could access the freedom of this alternative world, the ideal which was in such stark contrast to reality, by changing the way he thought.

On the first page of Tropic of Cancer he enthuses: “I have no money, no resources, no hope. I am the happiest man alive” and in Tropic of Capricorn he says: “To be civilized is to have complicated needs. And a man, when he is fully blown, shouldn’t need a thing”.

In the latter book he expresses his desire to spread that outlook to others, seeing this as a means to sabotage the industrial system: “I want to prevent as many men as possible from pretending that they have to do this or that because they must earn a living. It is not true. One can starve to death – it is much better. Every man who voluntarily starves to death jams another cog in the automatic process”.

Miller sees the escape route from the industrial nightmare as beginning with an inner journey “for there is only one great adventure and that is inward toward the self”. (Tropic of Capricorn)

He describes the self-purifying process, often described as spiritual, by which we can burn off all the despair and nihilism in order to grow ourselves again from the bare scorched earth of our renewed selves (I try to describe this process, and its importance for would-be revolutionaries, in The Anarchist Revelation).

Miller writes: “If one isn’t crucified, like Christ, if one manages to survive, to go on living above and beyond the sense of desperation and futility, then another curious thing happens. It’s as though one had actually died and actually been resurrected again…” (Tropic of Capricorn).

We have left any apparent negativity far behind us now. Here is, in fact, the ultimate in positivity, an embracing of the affirmative act of being joyfully alive from the core of your stripped-down, resolved, being.

“Only one like myself who has opened his mouth and spoken, only one who has said Yes, Yes, Yes, and again Yes! can open wide his arms to death and know no fear”, writes Miller in Tropic of Capricorn.

With his distrust of some forms of spirituality as a flight away from the fullness of physical existence, including the sexual encounters which he takes such delight in describing, Miller has no doubt as to from where he draws the primal strength of his fearless and uncompromising will to life.

He declares in Tropic of Cancer: “Once I thought that to be human was the highest aim a man could have, but I see now that it was meant to destroy me. Today I am proud to say that I am inhuman, that I belong not to men and governments, that I have nothing to do with creeds and principles. I have nothing to do with the creaking machinery of humanity – I belong to the earth!”