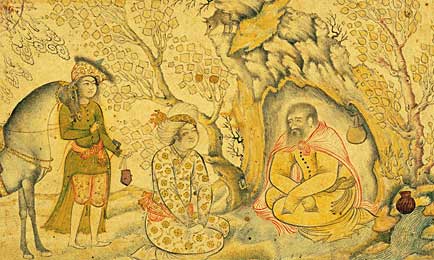

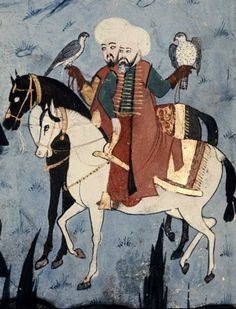

One day while he was sitting under an olive tree, contemplating the earth, the sky and the dimensions of the cosmos, there came to the wise Perantulo a man on horseback. His face was obscured by a richly decorated silk scarf and he was accompanied by a dozen mounted warriors, whose scimitars glistened in the sun.

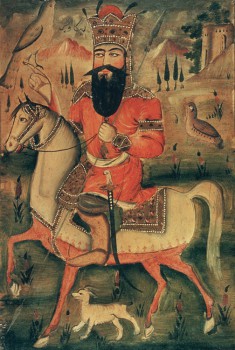

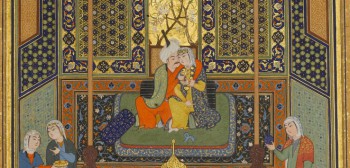

The man was none other than the Sultan of Khaluvia, who had received word of the teaching, the healing and the presence of Perantulo and wanted to see for himself this legendary fakir. The Sultan dismounted and approached the sage, unwinding his scarf so that he could be fully seen. He was plainly of noble character and had the look of one endowed with both intelligence and mental strength, but Perantulo saw at once that there was much that separated him from Knowledge. Having ascertained that this was indeed the sage he had been seeking, and after whom he had been enquiring for many days, the Sultan looked silently into Perantulo’s eyes and Perantulo looked silently and unflinchingly back. This moment stretched out until it became uncomfortable for the Sultan’s warriors, who did not understand what was happening and longed for it to end. But none dared move so much as a muscle or utter so much as the softest of whispered sighs as the two men remained locked in mutual scrutiny.

Finally, the Sultan dropped to his knees and, with tears welling in his eyes, declared: “Never before, Perantulo, have I seen in the eyes of man or woman what I have just discovered in yours. I must confess that I have wondered these last days whether the rumours of your wisdom were not exaggerated by the loose tongues of gossiping embellishers, but now I know that their inaccuracy strayed in the opposite direction to that which I had feared to be the case. Your reputation does not do you justice, Perantulo, and I say this without having heard you utter one word or move one finger. I beseech you, O Holy Man, to show me how I can see what you see, know what you know, shine as you shine”.

There was a long pause. Perantulo remained so still that a small green lizard walked up one arm, across the back of his neck, and down the other.

And then he told the Sultan: “It is a fine thing, O Great Ruler, that you have come here and spoken thus. Your people are fortunate indeed to be led by a man of your sensibility. But it is no easy thing you seek. The path is long and steep and you would do well to bear in mind the fable of the traveller who feasts on his supplies in celebration at having reached the lofty summit of his destination only to realise, when the mists lift, that he has merely conquered the lowest of the foothills that come before the plain that leads to the sea across which lies the mountain he would ascend”.

“I know the path is long, kind sage. Fear not – the mist of impatience will not blind me on my journey,” spoke the Sultan.

Perantulo waited for another long moment – moments for him bore little relation to the moments of ordinary men. He was so still that a golden butterfly alighted on his upper lip and preened itself for a while before fluttering on its way.

“Very well,” said the old philosopher to the Sultan. “But you should know that the task ahead of you involves three stages. The first, which is quick and easy, is to express the Desire for True Knowledge. The second, which will be painful to you and to those who love you, is to rid yourself of all obstacles that can prevent the Torch of Eternal Truth from shining through you. This stage is dangerous for one whose commitment is not complete, for one who is not strong enough to bear the hatred of others or for one who is not supple enough inside to absorb the hurt. It is a dark voyage from which you may never emerge, O Sultan-most-Splendid”.

The Sultan, a pensive frown creasing his brow, drew a deep breath: “And the third stage, O Holy Perantulo?”

“The third stage,” replied the fakir, “can only be imagined when the first two stages have been completed”.

The Sultan nodded. “So be it,” he said. “I have understood”.

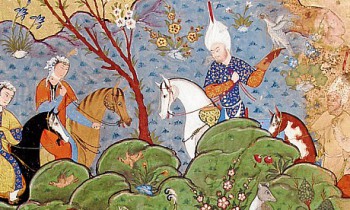

And then he sprang to his feet, turned to his bemused men, and roared: “Let you all stand witness, my warriors, that your master, the Sultan of Khaluvia, today expresses his unquenchable commitment to the Desire for True Knowledge, that from this moment forth his days among mankind will be devoted to no other cause and that nothing and nobody can stand in the way of his Quest. Now we will ride, ride, ride – back to our famous City of Alzorika, which will soon become famed not just for its wealth, its learning and its arts, but for the devotion of its 75th Sultan to the Glory of All Being!”

He leapt on to his horse, raised his sword in the air as a sign of his energy and determination, then span to face the sage, who was still seated under the tree.

“Perantulo!” he cried, the fire of zeal scorching from his eyes. “Perantulo! I have heard your words and I will hold them in my heart! I will return!”

At that, he span his horse round, let out a mighty cry of inchoate resolve, and then he and his soldiers headed back off across the grasslands in the direction from which they had come.

During the Sultan’s impassioned declaration, Perantulo had started to open his mouth as if about to speak, but had then decided against it. He watched the party disappear into the distance with the faintest hint of a sad smile upon his lips.

As he rode back to his palace, the Sultan said to himself: “Perantulo has warned me that this second stage will be dangerous and he alluded to the possibility that I will not go far enough in my efforts to remove all obstacles to the Torch of Truth. I owe it to him to ensure that I have heeded his warnings and I will not return to him to ask about the third stage unless I am sure that the second has been completed”.

He resolved that every time that he felt he had achieved what had been asked of him, he would sit and imagine the old man sitting opposite him, listening to his account. The look in the eyes of the sage would tell him whether or not his efforts were yet sufficient.

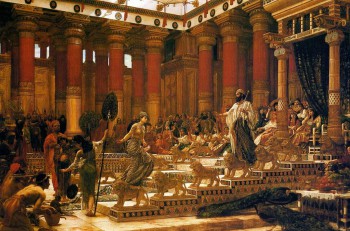

When he arrived back to the domes, turrets and minarets of his magnificent capital city, the Sultan knew at once what he had first to do. He ordered his servants to clear the palace of all the sumptuous decorations of which he had always been so proud and to place them all under guard in the enormous covered market of Alzorika. Obeying without question, but with bewilderment written all over their faces, the servants pulled down lavish wall-hangings, carried off bronze statues and elegant urns, removed the golden medallions from the pillars of the Banqueting Hall and even, at the specific insistence of the Sultan, fished the rare multi-coloured fish from the fountain in the Courtyard of the Khaluvian Kings and took them away in glass tanks. There was only one wing of the palace that was exempt from the purge and that was the domain of the Sultan’s wife.

When all the splendid items had been laid out in the market halls, the Sultan had his men invite the poorest people of the city – widows, cripples, half-wits, freed slaves, scavengers and water-bearers – to come to the halls and each take one item of their choice. Whatever was left was offered to the next neediest section of the population, until all was gone from the halls and distributed around the slums.

The Sultan did not need to consult his mind’s image of the wise man to know that this was, in itself, not enough. He immediately instructed his cooks to prepare only the simplest meals for him and his court – the excess of fine meats, truffles, sugared almonds and honeyed delicacies from all corners of the Empire was to be disposed of as they saw fit. They were, however, to retain sufficient supplies to maintain the luxurious standard of living enjoyed by the Sultana and her immediate household, which included their two sons. The Sultan had no wish to incur her wrath and so far he had managed not to alert her to what he was doing.

As he pondered what his next move should be, the Sultan gazed into the fountain, which looked so plain and yet so pure without its former denizens. When he caught sight of his own reflection, he knew what had to do. He retreated into his quarters, took off his heavily-embroidered silken finery and ordered his manservant to fetch him a simple wool tunic of the kind worn by the lowest order of priests. He then had the contents of his wardrobe taken in ox-carts to the countryside, where they were handed out to the peasants tilling the fields and to the free men who eked out a simple existence in the great forests of the Pommonic Hills.

Alone in his stripped-out quarters, dressed in his plain tunic, he pictured himself telling Perantulo what he had so far achieved. The look in the old man’s eyes was not encouraging. It seemed to reach straight past the Sultan to the palace in which he was standing. Even deprived of its lavish decorations, it was a magnificent building – and far too grand for a humble truth-seeker such as he aspired to become. He decided he would have to move out.

Just then, there was flurry of voices and footsteps in the hallway outside and the Sultan’s wife, Yoloccina, came sweeping into the room accompanied by some of the leading dignitaries of the city. “What is the meaning of all this?” she demanded, waving her hand to indicate the emptied-out rooms of the palace beyond her own wing.

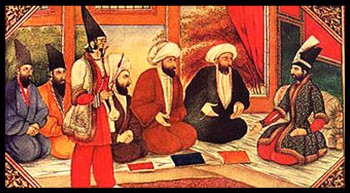

She was not happy and neither, it turned out, were the merchants and money-minters of the capital, who had been mightily offended by his decision to give away his riches to the poor. “Your Highness, do you not see that your most loyal and devoted servants, the cream of the empire who have worked hard throughout their lives to attain the high-ranking status they enjoy today, cannot fail to be hurt by your actions?” enquired the Master of the Ostan of Alzorika. “Were you to have distributed this great wealth equally among all your subjects, including those of the higher classes, their pain would perhaps be less severe, but to bestow your favours uniquely on the lazy, the inadequate, the lowest dregs of our society…”

The Sultan held his head in his hands. Was this what Perantulo had been warning him of – the negative reaction of others to his righteous efforts? “Enough!” he shouted at length, interrupting a bitter complaint from the Guild of Master Butchers about the adverse impact of free meat on its members’ takings. “Enough of all of this! I am the Sultan and you will not presume to tell me how to manage my affairs!”

Dismissing all of them except for Yoloccina, he then told her that he would be moving out of the palace forthwith and dispensing with the services of his personal staff. She was welcome to keep her own wing, but he, for one, would from now on be living in one of the small houses in the outer grounds built 50 years ago to house the mercenary soldiers who came to fight in the Great War of the Razor’s Eye and which were kept empty and waiting in case there was ever need for such visitors to return. When he refused to listen to her objections, she stormed off, crying that she would never so much as look at him again so long as she lived.

A terrible mood of self-doubt overcame the Sultan as he sat in his sparse new home, all alone and contemplating the bowl of spiced chick-peas and the chunk of coarse black bread that was to be his evening meal. All the eager-to-please faces that usually surrounded him were gone, his two sons were out hunting so could provide no company for him, and even the mealtime absence of the Sultana, difficult woman though she was, left an empty feeling in the pit of his stomach. What sort of life was this for a Sultan?

With that thought, he leapt to his feet. Of course! That was the core of the problem! Why hadn’t he seen that before, rather than worrying about the surface details of his regal life? It was his Sultanship itself that was the obstacle to the Truth. He called for his legal advisors and within an hour had signed a document ceding his title to his elder son, the traditional heir. He himself was no longer the Sultan, but Askush – the name by which he had been known as a young boy. The new Sultan and his brother were due back to Alzorika at any time now, so although the deed was done, he would delay the general announcement until he had spoken to them.

Askush broke the news to the two of them together and they both received it with barely a flicker of emotion crossing their faces, as befitted their station. But when he spoke to each of them in turn, on their own, a different picture emerged. The younger lad was upset not because he himself would not become Sultan, which he had no reason to have expected while his brother was alive, but because he feared it would alter the relationship between the siblings. He felt that the older lad had often sought to gain an advantage from his greater experience and the fact that he was heir, and that, while they had reached an agreeable equilibrium of late, his sudden succession to the throne would bring out the worst in him. There was a tear in the lad’s eye as he reflected that the hugely enjoyable hunting trip from which they had just returned could well prove to be the last occasion on which the pair would spend time together on an even footing.

For his part, the elder son was not pleased to be inheriting his father’s mantle so soon, it appeared. He had always known that one day the privilege and responsibility would be his, but he had hoped, in all frankness, to have enjoyed the carefree days of his youth without the serious obligations involved in being Sultan. Since his father was not yet old and was in evidently rude health, he had not mentally prepared himself for the assumption of this burdensome role. Despite it being impressed upon him that the legal transfer of power had been completed, he begged his father, with tears in his eyes, to reconsider his decision.

When they had both departed, Askush collapsed on to his simple bed. He felt completely drained. How had he managed to create so much unhappiness by following a path with the worthiest of intentions? When he thought of the tears of those two strong young men, who had been so close to his heart for so many years, he himself began to sob and to sob, filled with a perplexing mixture of remorse and confusion.

In a while he fell asleep, but was rudely awoken after less than an hour by a hammering on his door and windows and a great hubbub in the street. Half the city seemed to be outside his new home and they were screaming their frenzied hatred of the man they had now been told was their former Sultan. He was a coward, they were saying, a weak-willed traitor who had let down his faithful people. Peering out of a small upstairs window at the crowd, Askush noticed several members of the disgruntled merchant classes whose dissatisfactions he had learnt of earlier in the day. But the great majority of the mob consisted of the common people, the poor – the very ones who had benefited from the disposal of his wealth. He understood that the merchants must have been busy whipping up anger in order to gain the support of the very classes they despised, but he still could not help feeling a crushing disappointment that the people of Alzorika had turned against him.

The angry mood finally wore itself out for the evening and people started dribbling away, shouting that they would be back in the morning. When he was sure they were all gone, Askush crept out, made his way to the stables, saddled his horse and rode away into the night.

It took him three exhausting days to find Perantulo, who had moved on from the olive tree where they had last spoken. There were moments when Askush felt like giving up the effort of searching and just riding off somewhere else and forgetting the whole thing. In his heart, he wanted to go home, back to the life he had known, but it was too late for that now. Askush felt exhausted by what he had experienced since he had last spoken to Perantulo. He felt that he had lost everything that he had ever had and that he had aged at least twenty years in just a few days. But at the same time he felt consoled by the knowledge that he had done what he had to do. By the time he finally reached the sage he had managed, despite all the sadness eating away at his heart, to enthuse himself with the thought that now that the second stage was complete he would be entrusted with knowledge of the third stage that lay ahead.

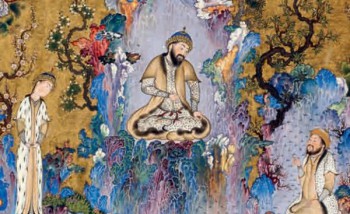

Perantulo was seated on a stone in the middle of a small river, his legs dangling in the water. He seemed to be completely absorbed in watching the ever-shifting patterns in the flow of the stream and the rippling of reflected sunlight shimmered and eddied across his lowered face.

“Good day to you O Perantulo!” declared the dismounting horseman.

“Good day to you, too, O Askush!” replied Perantulo, not even raising his eyes.

Askush was astonished that he had addressed him by that name, but resolved to say nothing about it and to continue with his account as he had composed it in his mind, regardless of whether the old man somehow already knew of all that had passed.

Somewhat breathlessly, he told Perantulo every detail of what had happened to him in Alzorika, confident that he had surely achieved all that was possible in his bid to complete the second stage and rid himself of all obstacles that could prevent the Torch of Eternal Truth from shining through him. The third stage would soon await him and sweep away the trauma of the terrible sacrifices he had just made.

When he had finished, there was a long silence while Perantulo sat calmly on his stone in the river, gazing into the flow. He was so still that a great silver fish leapt from the water onto his lap, gobbled up a fly that had landed there, and then wriggled and plopped back into the stream.

Finally, he raised his head and spoke. “Askush,” he said. “Your account fills me with me with great gladness for you have now successfully achieved the first stage of the journey on which you have embarked – by your actions you have indeed expressed your Desire for True Knowledge. But now, my friend, comes the second stage and here your real effort must begin”.

The Sultan and the Sage is the first chapter of The Fakir of Florence: A novel in three layers, which is available to buy here and from Active Distribution

Leave a Reply