We tend to think of knowledge in terms of acquisition – we see ourselves as adding new pieces of information to our existing mental stock. But sometimes it is more a process of removal – a pulling away of veils that have been hiding a truth we somehow always knew, deep down, but could not quite seize or articulate.

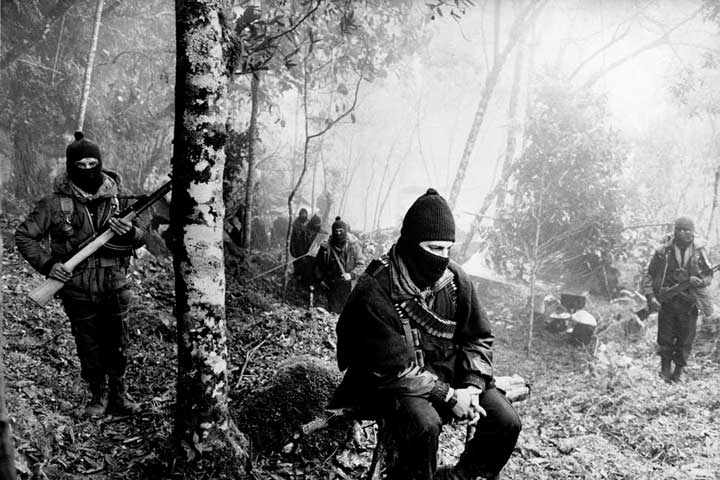

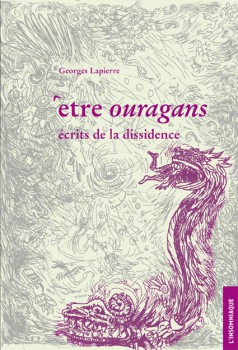

This is very much the case with a book I recently borrowed from my local anarchist library, written by Georges Lapierre, who was co-author with Yves Delhoysie of the 1987 classic L’Incendie millénariste. This 2015 work published by L’insomniaque, être ouragans: écrits de la dissidence (roughly “Being Hurricanes: Rebel Writings”), runs to 680 pages and consists of three distinct parts – the first one explores our perception of reality, the second looks at the origins of capitalism and the third focuses on current resistance and repression in Mexico, including the indigenous struggles in Oaxaca and Chiapas.

The main insight I personally gained from the book concerns the fundamental character of our modern “Western” society and why I have always found it distasteful, even before I had my youthful head screwed on well enough to understand why.

Lapierre insists that what marks our civilization, and separates it from other cultures past and present, is that it is an entirely mercantile culture. This is not just the way it organises itself, but the way it sees, the way it thinks. The “cosmovision” of our society, to use Lapierre’s term, is based entirely on money, on the exchange of money. As he puts it: “In a mercantile society we are all merchants, our heads are filled with the thoughts of big capitalist merchants, we all think about money.”

The implications of our descent into a money-based cosmovision are enormous. We find ourselves in a hollow and superficial world entirely dominated by Oscar Wilde’s cynics, who know the price of everything and the value of nothing. Lapierre looks at other cultures in which gift-exchange plays a crucial role in communal cohesion and at the way in which the mercantile attitude amounts to a separation of the individual from the collective. This stranded individual becomes nothing more than a helpless slave to the system.

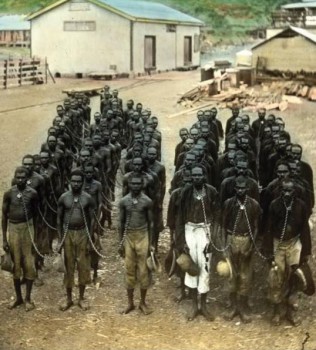

He explains: “From time immemorial, the slave has been the one reduced to being nothing but an individual, someone separated from their community or from their people, someone who is no longer driven by their own thought (in other words, the thought of the collectivity to which they belong) but by that of their master”.

At times, Lapierre seems to shake his head in astonishment at how this ever came about, at how a mentality so alien to every healthy human culture could have come to dominate the species. He writes: “Let’s not forget that in a traditional society the merchant is the stranger, the one who doesn’t respect the rules of the social game, and here we have this being who has set himself apart from society, who doesn’t take part in the interplay of mutual obligations and who only acts in his own interests, and is now poised to conquer the planet”.

He makes it admirably clear that this mercantile domination is not something that has evolved peacefully or somehow emerged naturally through any kind of consensus. The capitalist world-view has always been imposed by force. He cites the example of Australia where “the Aborigines had to submit to the idea of exchange held by the British colonists, or else disappear: massacres, deportations, reserves or concentration camps; the indigenous people and their way of seeing the world do not interest the British colonists, they are wiped out or fenced in”.

Again and again, says Lapierre, “absolute violence” has been used to impose the rule of money: “Violence is at the heart of capitalism… To submit to the capitalist system-world, consciously or not, is always to do violence to yourself”. As well as violence, there is deceit. Part of the totalitarian domination of mercantile thinking involves the hiding of the mercantile nature of our society, the induced forgetting of the notion that there could ever be another way of living. Our master’s voice tells us – from within our own colonised minds – that all this is quite normal, commendable, necessary, that it is simply “real life” to which we have to adapt and succumb.

This lack of consciousness is one of the veils that prevent us from understanding our society – the others include any inadequate critiques of our contemporary society which do not embrace this fundamental problem of a mercantile mindset. One of these is Marxism, says Lapierre. He points out that Marx’s analysis of capitalism came very much from within the capitalist system itself and thus remains trapped inside the mercantile cosmovision: “In fact, Marx never challenged the form of exchange with which he and his contemporaries were already familiar. He grasped its workings, and criticised them, but he didn’t criticise its spirit, or barely so”.

Lapierre concludes that the class theory of society simply does not explain the depths into which our contemporary civilization has sunk. He insists that authentic opposition to capitalism can never arise from within a broadly capitalist mindset and can never merely amount to attempts to reform capitalism, to make it nicer and more liberal or to place it under the control of a different group of people.

“It’s not about winning power and taking over the state, but about fighting power, opposing any project coming from above or elsewhere. It’s on the terrain of resistance to a capitalist project – mines, dams, wind turbines, monoculture, factories making consumer goods, high-voltage power lines, motorways, high-speed rail lines, etc – that you can judge the reality and validity of a struggle, its authenticity. All other forms of action – fights against poverty, for decent wages, for jobs, for access to goods, for shelter, for culture, for fuel, for education, for citizenship, for democracy etc – hand victory to the mercantile world.”

Although Lapierre’s book both inspired and informed me, I have to say that I do have some significant differences with more theoretical aspects of his analysis. Notably, he takes great exception to the concept of “nature”, which he regards as the outcome of humanity’s separation from the world around it: on one hand there is humanity, the subject, and on the other hand there is an external object called “nature”.

While this is indeed one way in which the word is currently deployed, it does not have to be interpreted in this way – take, for instance, the slogan much loved by French eco-activists which declares that they are not defending nature but are, instead, “nature defending itself”.

Do we have to invent an alternative “acceptable” word to describe life on the planet, of which humankind is a part? For me, it makes sense to reclaim the use of the word “nature” in its fullest sense rather than throw it away because it has become somehow contaminated by misuse.

Lapierre extends his antipathy to the word “nature” by rejecting the concept of human nature, which he says is used to “enslave man”. For him, the human being is characterised by “a brain practically empty of all content at birth” and he adds: “The human being is a concept”. For Lapierre, society is everything, it seems, and the cosmovision of the mercantile society of today completely shapes human beings living within it, in the same way that the cosmovisions of other cultures past and present shape those living in them.

This does not ring true to me. If absolutely all our thinking comes from the society in which we are raised, how can we ever come to think outside of that society’s mindset? How did Georges Lapierre, for instance, ever manage to find himself on the outside of the mercantile cosmovision, criticising it so effectively?

If I was born as pretty much a blank piece of paper and mercantile culture’s assumptions were subsequently written all over me, how was it that at a certain point when I was young I realised that something was badly wrong with that same mercantile culture? Even if my initial response was unfocused, what exactly was there inside me which had remained distinct from the culture in which I had been raised and which enabled me to view it critically, to sense that it did not correspond to what I regarded as “right”?

Here, we return to the idea of the attainment of knowledge as being an unveiling of truths already known. Why do thinkers of the left (including Lapierre, evidently) have such a problem with the idea that human beings are born with certain innate qualities, potential and expectations? We don’t find it impossible to understand that a bird is born with the innate ability to build a certain type of nest, for instance, but the idea of equivalent capacities in human beings seems to alarm people.

Obviously, human beings are not bound by their instincts in the same way that other animals are – and this is a significant difference. But this does not mean that those instincts are not still there, even if often buried by cultural requirements.

Is it not possible that there is such a thing as human nature – not a falsely universal version imposed on people by centralising colonisers, but a real, living, organic, indefinable one? Is it not possible that this authentically universal human nature includes the instinct to live co-operatively, freely, without the wage-slavery, exploitation and misery of the money prison-world?

Couldn’t this be why you “do violence to yourself” if you submit to the present system in contravention of your natural inclinations? Couldn’t this be why people like Georges Lapierre and millions of others within the mercantile world continue to reject the inhuman anti-values of industrial capitalism, of the global mercantile culture, and to insist that another world is possible? And wouldn’t it be a good thing if this was the case, rather than a reason for ideological anxiety or evasion?

* I have a new book on the way! Nature, Essence and Anarchy is currently in the Winter Oak production process and will be out fairly soon, all being well.

Leave a Reply