The artificiality and abstraction of life under contemporary capitalism is dragging us further and further way from a real sense of being alive – in our bodies, in our daily lives, in our environment.

That is the crucial message from anti-capitalist philosopher and writer Renaud Garcia in his latest book, Le Sens des limites: contre l’abstraction capitaliste (Paris: L’Échappée, 2018).

A new call has to go out to humankind, he says, particularly to its youngest generations, warning of this debilitating loss of contact with physical reality and demanding another way of living.

This could come from amongst radical environmentalists and anti-industrialists and “from the best of the anarchist and unorthodox Marxist traditions”, he says.

Garcia caused quite a storm in 2015 when he warned in Le Désert de la critique that certain postmodernist strands of thinking were diverting left-wingers into a dead-end of disempowerment and irrelevancy.

I wrote about some of the issues he raised in my 2016 book Nature, Essence and Anarchy, a chapter of which is available here.

In his 2018 book, Garcia draws much of his positive inspiration from the world of literature, quoting authors such as Jean Giono, Edward Abbey, Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann, Franz Kafka, Philip K. Dick and J.G. Ballard.

He describes our Western world as “a civilization with money as its universal mediation” in which capitalism “encloses” and privatises all aspects of life.

It cannot tolerate the idea of anyone living outside of its enclosure, hence its need to stamp out the practice of “subsistence” farming, where communities have the cheek to simply produce enough food for their own requirements, rather than for the requirements of the capitalist profit-machine.

It forces people into its system by giving them no choice, he explains: “Declaring war on subsistence means dissolving the autonomous ways of life of thousands of people and thereby enslaving them to commercial needs which they can only fulfil by going out to earn a wage”.

Garcia devotes an important section of his book to condemning the capitalist concept of “work”, which it has tried to persuade us has always been a “natural” part of human life.

He points out that this is not at all the case: “It only came into existence, as a basic social function, when the capitalist system solidified and expanded, at the turning point of the 17th and 18th centuries in England”.

The primacy of “work” in our modern society devours any deeper sense of existence and purpose, says Garcia.

“‘What do you do in life?’ This familiar question, which is supposed to be the first point of contact with another person, says a lot about the place that work takes in our lives. It reduces the individual to what he does in life, thus supposing a central role for work, which fills the otherwise neutral space of life”.

Garcia reminds me of Ferdinand Tönnies (with his contrast between communal Gemeinschaft and commercial Gesellschaft) when he draws a distinction between what he calls “vital praxis”, an individual’s effort and contribution to the community, and “abstract work”.

He explains that “work”, in this latter capitalist sense, is not about actually doing something useful or creative. It is just about spending a certain amount of hours in paid employment, the value of which is irrelevant.

As with everything else in this empty society, it is purely about quantity (of hours, of money) rather than about quality.

Garcia regrets that so many on the left remain fixated with the capitalist fetichisation of work and even regard it as central to their anti-capitalist struggles. This, he concludes, is “a blind spot for the whole of traditional Marxism”.

He refers to Moishe Postone, whose analysis falls flat, he says, by putting forward “a critique of work under capitalism rather than a critique of capitalism from the point of view of work.” He adds that it is no coincidence that Postone rejects critiques of industrial society as romantic and backward-looking and writes about the importance of maintaining high levels of productivity.

Garcia argues that it is pointless to merely point out the contradictions of capitalism, while remaining attached to the excessive optimism regarding technological progress that is essentially itself part of capitalism.

He declares: ” If we want to develop a critical theory of society which is not content with mere adjustments to the centre of the system of producing goods (defending ‘jobs’) or on its fringes (through a more quality-orientated form of economic growth) then we will definitely need to imagine going beyond work. This aim might well seem utopian, but it is also precisely the most realistic way of escaping from the false life of this economic abstraction”.

The idea of defending a natural world, which includes human communities’ relationships with the environment, has been neglected by Western anti-capitalism, he says, particularly under the influence of mainstream Marxism.

Uprooted from our previous rural existences, we today often find ourselves living in a sterile and life-denying suburban sprawl, a space created “for the demands of capital”, where people are trapped in a dependence on their cars and thus on the oil industry.

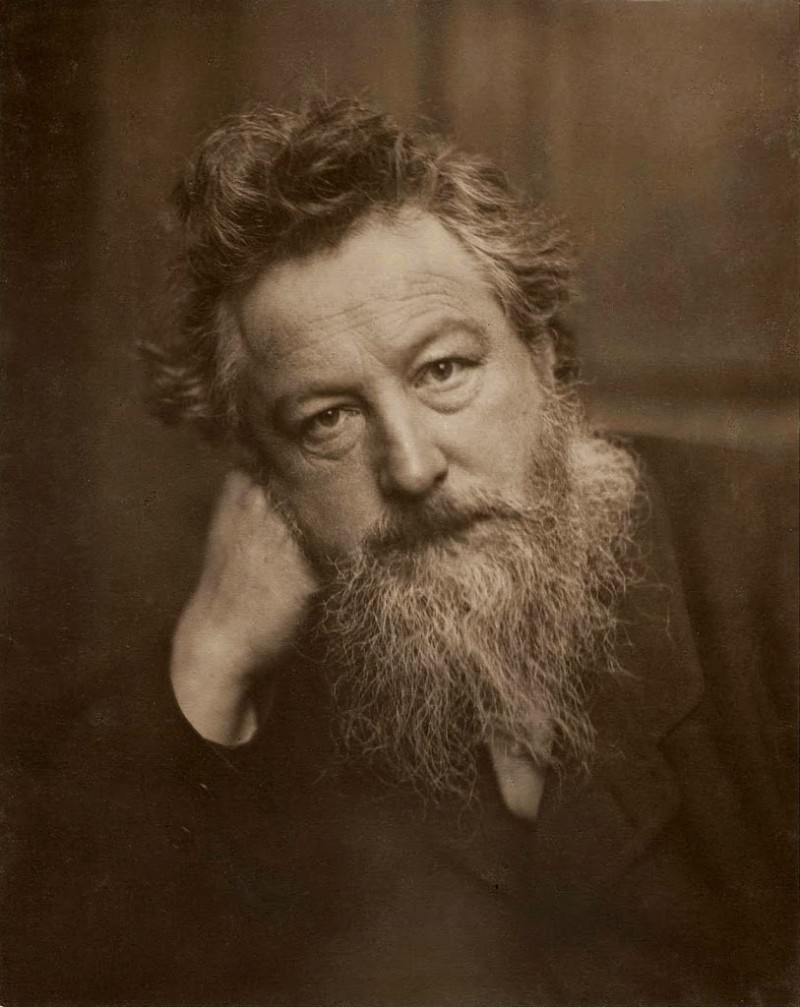

Garcia draws much on William Morris and echoes his critique of the artificiality of industrial capitalism: “In this world of artifice, going beyond the surface to a deeper level, that of the sheer essence of things, is no longer conceivable”.

In place of this, he yearns, like Morris, for a different, socialist, world, where quality rather than quantity is the guiding principle: “Opposed to the world of having, this world of being will differ from it in the same way that a cultured eye differs from a vulgar eye, a musical ear from a non-musical one, a stiff and clumsy body from a supple and graceful one, a finely-developed sense of taste from one brought up on the quick sensations of ersatz industrial food”.

Garcia dedicates another section of the book to examining, and condemning, transhumanism, which he terms “the official ideology of technological capitalism”.

This ideology “reduces the human brain to a simple processer of information, a mere calculating machine” and is built on the “basic negation of the reality of living organisms”.

Behind it lurks a “brutal dualism” which regards mind and body as completely separate, and thus imagines the possibility of a “posthuman” self with no fleshly existence.

Worryingly, this ultra-capitalist creed is also embraced by some who term themselves left-wing and have swallowed the lie that technological and social progress amount to the same thing.

The UK transhumanist Kevin Warwick wrote in I, Cyborg (2002) that his robotic future would leave behind those human beings who refused to abandon their real bodily existence and separate themselves from that hopelessly reactionary concept of nature: “If you are happy with your state as a human then so be it, you can remain as you are. But be warned – just as we humans split from our chimpanzee cousins years ago, so cyborgs will split from humans. Those who remain as humans are likely to become a sub-species. They will, effectively, be the chimpanzees of the future”.

Garcia concludes his work by turning this label into a banner of defiance against the arrogant industrial-capitalist elite exemplified by Warwick.

He says that his book could be seen as fuel for an ideological movement opposing the life-hating transhumanist nightmare, an anti-capitalist, anti-industrialist “party of the chimpanzees of the future”.

He can count me in.

Leave a Reply