A Brief and Incomplete History of Squatting in Brighton (and Hove)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Version Six September 2012

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Previous versions have been made available for free as a zine.

Click on the scanned images if you want to view them as higher resolution.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Introduction

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Squatting in Brighton has a long and illustrious history, some of which is captured here. If you want to add or correct something, please email.

We are attempting to record here the hidden history of squatting as a political tool but it is of course worth remembering that most squatting is completely secret and pretty much undocumented. People squat for a whole host of reasons including poverty, housing need and vulnerability. A recent Crisis report, the Hidden Truth about Homelessness, states that one in four single homeless people have squatted at some time

The politicised wing of squatting tends to get the media attention but it represents only one aspect of why people squat (although it does also fight for the squatting rights of all). Certainly the political squatters are a radical minority, but that’s what this history focuses on, because it makes for an interesting story.

Another point worth mentioning is that we are neglecting to cover the long tradition of travellers squatting land in Brighton and living in vehicles. This loose grouping includes New Age Travellers, Irish travellers and gypsies. Increased parking restrictions in the centre (eg round the Level) have pushed travellers towards the outside of town, but landsquats (sites) still happen down at the seafront, in Moulsecoomb Wild Park and other places.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Early Days

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Back in the day, presumably quite a bit of land was acquired by squatting it. Just down the coast in Hastings, a community of squatters laid claim to land created after a storm in 1287, at one point claiming to be the 24th state of the United States before being evicted. The land was called the America Ground.

Closer to home, someone posts on mybrightonandhove:

My family owned and ran Hodshrove Farm, which was then sold to the council and became known as “The Bates Estate”, which is now Moulsecoomb. My family moved down here in the early to mid 1800′s from Derbyshire. It is thought that the head of the family, Joseph Bates, moved down here to take on an estate management job for a wealthy Brighton resident up by Preston Park. It is thought that maybe the circumstances changed and they pitched up on the land, where Moulsecoomb is today, and ringed a fence around it. Effectively squatting. However, the law at the time stated that however much land you can fence in one night was legally deemed as your own. Thus the birth of Hodshrove Farm and nurseries.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

1920s

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Harry Cowley and the Vigilantes took action to house ex-servicemen and their families.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

1940s

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

In recent times, squatting became an issue in the late 1940s, following World War II. Servicemen returned to the UK with nothing and with nowhere to live, since their houses had been destroyed. Let down by the Government’s empty promises amidst the chaos of postwar reconstruction, they took direct action and occupied various unused army bases and empty buildings. The Mass Observation Archive at the University of Sussex has some fascinating first hand reports. Down in Brighton, that colourful character Harry Cowley and his Vigilantes were again squatting empties for families.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

1970s

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

After what appears to have been a lull, with records scarce, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the movement grew and became more political.

The issue again was housing. Steve Platt records in his chapter for the excellent book ‘Squatting: The Real Story’ that in November 1971 the Cyrenians, a charity for the single homeless which had become exasperated with Brighton Council, squatted three houses”. The Brighton Rents project was squatting buildings with widespread support (even Dennis Hobden, Labour MP for Kemptown, gave his backing). However, the Council refused to bow to community pressure and in July 1969, things came to a head. Houses in Queens Square and Wykeham Terrace were squatted. Platt records:

The army [ie Ministry of Defence], which owned the properties, had been intending to sell them with vacant possession, but the presence of squatters meant that this had to be postponed. The squatters dug in to fight and called for support. In the months up to the eviction (on 28 November) the local press pilloried the Rents Project and its helpers, warning of ‘private armies’ and ‘terrible weapons’ waiting at Wykeham Terrace. The dire warnings seemed to be validated when three people from the squat were arrested for firebombing a local army recruitment office. The petrol bombs had been made at the squat and several squatters were later sent to prison. These events were widely publicised with disastrous consequences. In Brighton for instance, squatting abruptly came to an end and the Brighton Rents Project disintegrated, torn apart by external hostility and internal divisions.

Over at mybrightonandhove someone claims that the bombs were planted by Special Branch. They are also mentioned on the Angry Brigade chronology, Brighton’s sole entry. It seems a bit of a mystery as to what really happened but we can certainly take this as an example of a time when the dominant discourse triumphed. Squatters were painted as the bad guys, using violence, even though the state always maintains the monopoly on violence, whether threatened or implemented. Certainly, in terms of the nascent squatting movement, the public had up to that point been quite sympathetic towards squatters who resisted eviction by any means necessary (for example in Redbridge and Fulham).

Two articles published in editions 18 and 19 of the Brighton Voice (a radical left wing newpaper published from 1973 to 1989) in 1974 spread a bit more light on the 1969 events. The anonymous author, who was clearly involved with the squatting actions, comments that the Brighton Rents Project was backed up the May Day Manifesto group of socialists, young socialists, international socialists, anarchists and communists. Students were involved.

The group campaigned on homelessness, surveying rented accommodation, keeping lists of empties and supporting rent registration by tenants. The Council appears to have dismissed the group and called the police when the project attempted to present a petition (eleven people were arrested). Beginning in May 1969 the group moved towards direct action, with two token occupations of houses which were later demolished. There were then two occupations in Terminus Road, two council-owned properties in Queen Square were squatted and the Drill Hall (stated to be ‘now’ the Sussex Sports Centre, not sure what that means) was cracked.

Then came Wykeham Terrace. It seems clear from this account that Steve Prior was an infiltrator who did indeed firebomb the Army Recruitment office only to smear the squat. It is also interesting to hear that the group eventually fell apart as a result of lack of support from the left generally and because of political factionalism between anarchists, socialists and communists.

In assessing the whole experience the author claims victory, contending that fifteen families were rehoused, the council was pressured into spending £700 renovating houses and the matter was kept in the public eye for month.

Regarding lessons learnt, these seem useful words:

On the press – ”the degree of press hostility depends on a leader writer’s stomach condition rather than logic, so don’t bother about press publicity, get your own”

On the public -”a large section of the public will not be swayed by either logical argument or humanitarian appeal to support you. they believe that homelessness (and by extension joblessness) arises from people being feckless layabouts. Show them any contrary evidence you like but they won’t believe you. So don’t waste your time trying to get them on your side: just be as truthful as possible as often as possible, but once you sense their belonging to this group, move on”

On the police – “police hostility is subtle, don’t underestimate it; it’s safer to be paranoic.”

Seeing as the police harrassment extended to agent provocateurs, phone tapping, arrests and workplace visits, it seems good advice indeed.

The Brighton Voice also mentions these squats:

- Mighell Street (April 1973)

- Brighton Road – Newhaven (1974)

- South Avenue in Queens Park (Feb 1974)

- Vere Road

- 32 Buller Road

- The Aquarius squat

- 2 Temple Gardens (more about this one below)

- 22 Montpelier Crescent (1975)

- 29 poynter road (1976)

- Buxton Road (1976)

Vere Road was violently evicted by Nicholas van Hoogstraten. The original Nasty Nick was an exceedingly unscrupulous landlord even by the standards set by other landlords (and we take a rather dim view of landlords in general). He was imprisoned for authorising a grenade attack on an associate and linked to the murder of Mohammed Raja in 1999 (but never convicted even though a civil court awared £6 million damages against him). He has a history of strong-arm tactics against squatters and tenants, pressuring people to leave with various underhand methods. Hoogstraten was later convicted over the Vere Road incident and fined £2,000 (Voice, issue 20).

With issue 23, the Voice sees the chance to declare “the squatting movement has hit Brighton and this time it’s here in a really big way”. There were thought to be 80 squatters in town in April 1975 and at the Open Cafe (7 Victoria Road) there was a list of empties on the wall. The Brighton and Hove Squatters Association was set up with two objectives, namely to provide instant accommodation for homeless people in Brighton and to publicise the property/housing situation.

Three people involved in this went on to become well known figures in Brighton, all for rather different reasons.

Tony Greenstein, who is now secretary of Brighton & Hove TUC Unemployed Workers Centre, a member of the trade union Unison and also a founding member of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign.

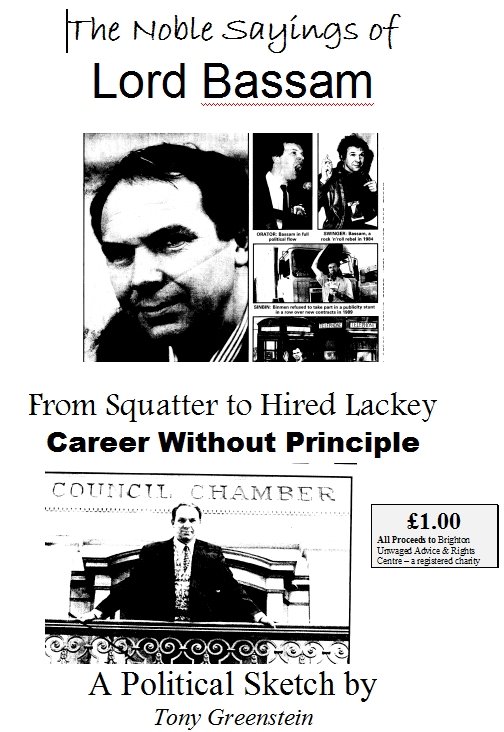

Steve Bassam, who led Brighton and Hove Council from 1987 to 1999 and is now Lord Bassam of Brighton, a Labour peer!

In the introduction to a pamphlet which he wrote on the sayings of ‘Lord Brownnose’, Greenstein observes that Bassam is “an example of the corruption at the heart of New Labour. It is a corruption that isn’t merely financial, although there is plenty of that but a corruption of the political process itself, which hides behind the soundbite and verbal chaff”. However, “those who live by spin and the soundbite will also die by them”.

Also active in the Brighton Squatters Union was Bruno Crosby, called ‘king of the squatters’ by the Argus in his 2002 obituary. By all accounts a charmer, ‘Big Bruno’ even managed to get the Tory Council Leader round to his Argyle Road squat for tea. This house had been empty for five years and was completely renovated by Crosby. In one copy of the Voice there’s a listing for the Brighton Squatters Union which says simply ‘Find Bruno in the Norfolk [pub] most nights’.

However, things could change pretty fast. Perhaps the squatters were the victims of their own success since the next mention of squatters in the Voice (issue 25) declares on the front page:

All over Britain in the last month, the squatting movement has been under attack. Not from the armed bailiffs of five years ago but from the worthless articulate hacks of many newspapers. The Sunday People recently carried out a four week group-probe into the London Squatters, during which reporters infiltrated squats and then wrote stories portraying them as the next cell of the revolution.

In the July15 Argus an article written by Gorringe entitled ‘Throwing out squatters’ advocated using thugs “indemnified against possible court action” – this might have had something to do with the Argus applying to the County Court for a possession order on 20 Granville Road, which belonged to the Southern Publishing Company and had been empty since some Argus journalists lived there.

In issue 26 (Oct/Nov 1975) the front page screams ‘Hired thugs in action again’. The squat at 2 Temple Gardens was attacked by heavies in one of SIX attempts to get them out before the court order was granted. A writer in the Voice opined “there is no issue about whether squatting is right or wrong. Homelessness is wrong and squatting is one way of doing something about it”. Students were encouraged to squat to free up property for those in need and also to stop rent prices rocketing (since landlords were able to charge £30 a week for 6 students in a house).

The article finishes up:

Of course squatting is an attack on private property: it should be. Not an attack on the houses themselves or a destruction of walls, windows or floors, but a principled attack on the iron law of property which rules our society, making it lawful for some people to have two, three or twenty houses and others to have none at all. It may be the law but it is not justice. Squatting is one way of bringing a little bit of justice into this ruthless society. MORE PEOPLE SHOULD SQUAT.

On August 12 1975, a big debate on squatting (100 people) was organised by the Young Conservatives at the Marlborough and there were estimated to be 150 squats in Brighton. So the number seems to be ever-increasing.

In 1976, a motion by Brighton Council calling on the Government to criminalise squatting was passed by 39 to 12 and indeed there were Parliamentary mutterings about banning squatting. However, the Campaign Against the Criminal Trespass Law fought an ultimately successful struggle to protect squatters rights, although various loopholes were closed in the 1977 Criminal Law Act (for example, possession orders could now be granted against ‘persons unknown’ meaning that the slightly farcical situation of named squatters leaving a place and different squatters immediately moving on was now prevented, theoretically at least) As part of the struggle, CACTL organised a meeting in Brighton with a certain Piers Morgan, who used to be active in the London squatters movement.

Moving to the end of the decade, the Squatters Union had a first birthday party – on November 6 1976 at the Art College, on Grand Parade. Admission was the princely sum of 40p, or 30p for members. In June the following year, Brittania House on Queens Road was squatted as a ‘Stuff the Jubilee’ action (Voice, issue 38) and it seems there was a coherent and influential squatters movement in Brighton.

As an indication of the impact which squatters had on urban planning and local politics, we have a quote from a Voice interview with Michael Elbro, Brighton’s new Housing Manager, who said in 1979:

I think that squatting is a symptom of the problem, it’s not a problem in itself, it is only so because of the laws of our land. as squatting becomes more vociferous then we need to sit up and think that there’s a lot wrong with the housing situation as it is. (issue 44 Feb 1978).

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

1980s

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Data for the 1980s is quite hard to come by, but it seems there was a continued political squatscene which revolved around housing for activists and students.

In 1986, the Brighton Bomber said: “There are many empty properties in Brighton which are being left to rot, most of which would make excellent squats. Why should we put up with living in expensive, tiny, often damp bedsits on our own, lining a landlord’s pocket.” [Issue 9]

Unfortunately the Voice does not have so much information as in the 1970s, although it does record in 1980 that the Sussex Housing Movement was set up out of the Squatters Union.

There was also the Portland Road story, where a squat was legalised but then evicted because of alleged theft of electricity.

Several housing co-operatives were set up out of squatted properties such as the Lorgan and Trumpton (pic below).

Two Piers, which the first co-op to have been set up in 1978, records in its history: “In 1982 squatters living at the Nook in Lovers Walk approached Two Piers to see if we could help them save the house and them from the Compulsory Purchase Order arising from the proposed railway development. We bought the house in 1984.”

Here are some fotos from a Housing Action protest which took place near the Clock Tower in central Brighton at some point in the 1980s:

Part two of the history continues here…

Feel free to email any info to snobaha AT gmail dot you know what.