Book review: Sivens sans retenue: Feuilles d’automne 2014

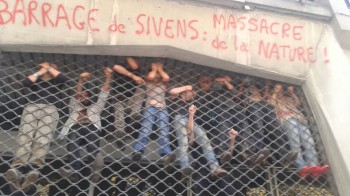

Of all the many projects opposed by protesters in France in recent years, the small dam planned for the rural southern valley at Sivens was hardly the most important.

But it quickly became a milestone battle in the growing struggle against industrial capitalism, thanks to the determination of the participants and the violence of the state’s repression.

On October 26 2014, student Rémi Fraisse was killed by a sound grenade fired straight at him, at point blank range, by military-style gendarmes.

The fact that the authorities lied through their teeth about the incident – suggesting for a while that he had been killed by something thrown by his fellow campaigners – only fuelled the anger unleashed by his death.

There were protests across France about his murder – “killed for economic growth” as one widely-circulated text had it.

But the significance of the protests lay perhaps more in an absence than in a presence – the absence of the massed ranks of the “left” who would normally be expected to turn out in reaction to the police murder of a youngster.

If the incident had taken place under a “right-wing” government, the reaction would have been different. But with a “left-wing” government and a “left-wing” local administration backing the barrage, opposition from those who consider themselves “left-wing” was muted.

By leaving the response on the ground to anarchists and radicals, this “left”, including the French Greens, revealed itself for what it was – a force for reaction. From now on, it was clear that the fight against industrial capitalism was going to have to come from below, from the streets, squats and rural hideaways of a new generation pushing for a radical, confrontational version of the significant French décroissance (degrowth) movement – a rejection of the whole neoliberal concept of “progress” and the assumptions that help bolster it.

However, it was not by chance that the Sivens struggle became the catalyst for a further radicalisation of an anti-industrial movement which had already spawned the full-on autonomous protest settlement, or Zad, at Notre-Dame-des-Landes in opposition to proposed new Nantes airport.

A book published in the wake of the high-profile conflict – Sivens sans retenue: Feuilles d’automne 2014 [Sivens without reservoir/restraint – papers from Autumn 2014] – reveals a deep radicalism embedded within the movement there, and expressed through various texts written on site, notably a daily bulletin from which the book gets its title.

An important part of this radicalism is a rejection of the limits enshrined within mainstream environmentalism – the book’s authors say that the anti-dam movement was “often weakened by a widespread and persistent trust in the state and by a desire for credibility in the eyes of the media”.

They characterise this environmentalist argument as being over-dominated by figures and statistics, mirroring the “scientific” vocabulary of the system it is supposedly fighting.

It also liked to frame the fight against the dam as being entirely peaceful, under any circumstances, a restrictive attitude which others could not accept.

“Our opposition therefore goes both beyond environmentalism and against it if necessary – against all its language borrowed from technocrats, administrators and politicians. Our opposition carries within it, admittedly in a rather unformed way, the dream of another way of living, free from commodities, free from the state and free from industrial work. A life which can only develop from below and which can, necessarily, only be realised through conflict”.

There is also a clear rejection of the idea of the threatened land as being a “zone”, labelled and protected by human beings who stand outside and above it.

Instead, the book uses as chapter heading a slogan that has appeared at Notre-Dame-des-Landes and elsewhere: “Nous ne défendons pas la nature, nous sommes la nature qui se défend” – “We are not defending nature, we are nature defending itself”.

As far as the Sivens project is concerned, the book makes it clear that it is a scam for the benefit of the local agri-industrialist farming establishment, designed to use public money to artificially stimulate economic activity and the private profit that goes with it.

Or, as one anonymous online article put it: “The real reasons for the project are simple: there is a local mafia who are, simultaneously, promoters, decision-makers and beneficiaries, and who have got together to grab 10 million euros from the public purse and divvy it up between themselves later. No need to look any further”.

Behind this immediate reality, the book suggests, lies a deeper gulf between the system that wants to plough ahead with such schemes and the people who want to stop them: “In the end, the story of the dam, which only involves a little reservoir covering some 40 hectares, tells us that this is not just an issue around grands projets inutiles [big useless projects] but about something much deeper; we haven’t got the same perception of life. The fortresses which they impose on our valleys, in our villages and in our towns are not invincible – the real dams are those in people’s heads”.

Here, thus, is a conflict of civilizations. On the one hand there is the neoliberal system, enshrined in the local and national political elite, which is always happy to sacrifice the land for the benefit of growth, development, profit. On the other hand there is another way of thinking, a peasant way of thinking, a much older way of thinking which is paradoxically now often represented by the youngest generation.

I use the word “peasant” because it is important to realise that, in France, being anti-industrial does not automatically make you a “primitivist” as it seems to in the English-speaking world. In a country with a much stronger and more recently-threatened rural tradition than the UK, the collective memory of other ways of living is still relatively fresh.

France is also twice the size of the UK, with much the same population, so the idea of vast open spaces lightly inhabited by people living close to the land does not have to be borrowed from visions of pre-colonial America – it is much more of a realistic possibility than it is in crowded, urbanised, degraded England, where the countryside is often the luxurious private preserve of those who have become rich by working for the global capitalist system.

This spirit is brought across throughout the book, for instance in the texts written by a collective of shepherds and shepherdesses whose opposition to industrialism is built around resistance to the compulsory microchipping of their flocks.

Here is a nice example, worth quoting in full:

“Capitalism’s domination of our lives has to be fought on at least two fronts. One of these is today clearly seen and understood by more and more people – it’s opposing all those infrastructure projects which manage areas so that commodities can circulate and various industries can function. This means the construction (or the extension) of high-speed rail lines, airports, power stations (whether nuclear, solar, wind or biomass…), commercial centres, the mass production of toxic foodstuffs, the sinking of fracking wells. In a very obvious way, all this destroys the countryside and covers farmland and forests with concrete.

“But there’s also another front which hasn’t been clearly identified and activated by enough people yet: opposing the colonisation of our lives by hi-tech devices. PCs, tablets, iPods, iPads, iPhones and the networks that support them cause colossal amounts of pollution and energy consumption, which put the effects of industrial agriculture in the shade. Pollution through microwaves, pollution through manufacturing and disposal, power consumption by the devices, by search engines, by data centres…

“We would need Zads [anti-industrial protest camps] in China, Africa and Bolivia to stop the extraction of rare earth metals needed to manufacture all the wonders of technology. We would need Zads in Ghana to stop the burial of all our junk made of plastic and toxic metals – last year’s novelties discarded with the arrival of the latest new product. We would need Zads in Mali and Niger to fight against the mining of uranium to feed the nuclear industry (which in turn feeds the internet in France). We feel a sense of solidarity with all every one of those Zads… even if, unfortunately, they don’t exist!”

(Collectif Faut pas pucer, October 2014)

The anti-industrial analysis presented by numerous contributors to the book understands that the role of machines in our society is not to “make life easier” for people, as the old lie suggests, but to enslave us. Our world becomes a machine. Our normality, our reality, becomes a machine. And it becomes unthinkable that this machinery should be impeded in any way.

Bertrand Louart, a local carpenter and cabinetmaker involved in the Sivens struggle, writes: “The general organisation of this enormously complex and intricate society has tied us in to a regulated sort of existence, to a tightly-policed way of life, to a level of activity that never stops, and which picks up speed the more it is regulated, policed and interconnected. Any interruption of this machinery, any intrusion of something unexpected or the unforeseen, something out of the box, out of the norm, is now regarded as ‘violence’.”

The real violence in our society of course comes from this machinery itself, in the form of a “legal” system which awards itself the unilateral right to use force against any opposition to its total domination.

The murder of Rémi Fraisse by this system necessarily focused minds on this aspect of the state/capitalist infrastructure, and the need to confront it.

An anonymous leaflet published three days after his death declared: “So that Rémi’s death resonates everywhere and sparks a real movement, we suggest that we organise locally and nationally against the infrastructure of the forces of order. It is this infrastructure which is behind the state terrorism with which are confronted in working class neighbourhoods and in our social struggles. It is this infrastructure which co-ordinates the police occupation of our land and of our existences. And it is this infrastructure which springs into action if ever a protest or opposition movement strays beyond the authorised paths of powerlessness”.

The leaflet sets out the whole mechanism behind “the armed gang known as the national police” and which could be paralysed by determined opponents. “The factories which make police’s grenades, uniforms and equipment, their vehicles and their TV propaganda, the logistical platforms that organise their supplies – for us, these are all targets”.

Not long after the murder of Rémi Fraisse, and the national publicity which surrounded it, the Zad was evicted by a combination of local fascists linked to landowners and a police force happy to turn a blind eye to their violence.

But the struggle is not over here – neither at Sivens nor, of course, further afield, and the book makes it clear that is the neoliberal system which ultimately has most reason to be afraid.

“It is fear that is spreading throughout the French oligarchy at the moment: fear that it will no longer be possible to launch infrastructure projects anywhere in the country without the emergence of a well-informed, determined and freely organised opposition. Fear that it will no longer be possible to keep the money machine rolling without humble members of the public loudly asking annoying questions: ‘What is the point of this project? Who stands to gain from it? What will be the impact on the place we live?’

“This is why it is so important, for the state, that a youth movement does not emerge that questions both the means (police) and the ends (capitalism) of its behaviour. Where would we be if schoolkids and students started calling for the disarming of the police, condemning with one voice the racist crimes frequently committed in our cities and the brutal repression of anti-capitalist protests? Where would we be if the various Zads against insidious industrial and commercial developments continued making links with each other, co-ordinating, coming together in words and action?”

And, from a UK perspective, where would we be if the powerful anti-industrial philosophy behind the Sivens struggle managed to spread across the Channel and recombine with the social wing of the anti-capitalist movement with which it shares its ideological roots?

Where would we be if the anti-fracking movement, the anti-climate change movement, the anti-roads movement, the anti-austerity movement, the anti-fascist movement, the movements against police violence and all those who hate this corrupt system looked up from the detail of their particular struggles and understood that their enemy is one and the same and that capitalism must be fought on every available front, in every single part of its ubiquitous infrastructure, if ever it is to be vanquished?

Sivens sans retenue: Feuilles d’automne 2014 is published (in French only) by Editions La Lenteur, Paris.