Long-term movement building, direct action and radical politics have a proven track record in the struggle against war

There are millions in the UK who support the antiwar agenda, but see protest as futile. If protesting against war is like protesting against gravity, it doesn’t seem worth taking time out from other commitments. Pessimism and hopelessness keep many sympathetic people away from antiwar activism, and so these doubts are important to address.

Antiwar movements can succeed

The movement against war in the UK has not received much attention recently in the mainstream media, and it’s easy to feel like there is not much we can do to overturn such a massive problem. But social change is nothing if not surprising. In 1964 it seemed impossible that by the end of the decade there would be an anti-Vietnam War movement powerful enough to force the president’s hand. Yet, despite these depressing appearances before the fact, that’s exactly what happened. In his best-selling People’s history of the United States, Howard Zinn makes the case that the explosive growth of the anti-Vietnam war movement had crucial effects on US policy, based on a wealth of sources, including leaked government documents such as “the pentagon papers”.

The evidence from the pentagon papers is clear – that Johnson’s decision in the spring of 1968 to turn down Westmoreland’s request [for 200,000 more troops], to slow down for the first time the escalation of the war, to diminish the bombing, to go to the conference table, was influenced to a great extent by the actions Americans had taken in demonstrating their opposition to the war.[1]

While the resistance of the people of Vietnam was almost certainly the decisive factor in the withdrawal of the U.S. from Southeast Asia, the documentary evidence shows that the role of the resistance at home was also important. Considering that massive expansion of the war – up to and including the use of nuclear weapons – was discussed several times at the highest levels, the effects of the movement for peace cannot be overlooked.

The challenges we face today in the UK are very different to those faced in 1964 in America. This time there is no draft to motivate dissent. On the other hand, antiwar activists were often met with incredulity and aggression in those days. Then, the majority believed the government was at least attempting to act in their best interests. Now this belief has been shaken, and there is a solid base of sympathy for the anti-war cause. Then, demonstrations before the war were tiny; this time we have seen massive numbers. Then, hopes of working people for an economically solid future were at their height; now those hopes are in the dustbin. The success of social movements is nothing if not unpredictable. But, building on what we can learn from earlier movements, and discarding mistakes, there are reasons to hope that the scale and power of dissent may be just as surprising this time around.

A movement with teeth

What was it about this movement that led to success? The same sources give a clear answer. In the leaked report on the reasons for turning down the 200,000 extra troops mentioned above, officials wrote that

This growing disaffection, accompanied as it will certainly be, by increased defiance of the draft and growing unrest in the cities because of their belief that we are neglecting domestic problems, runs great risk of provoking a domestic crisis of unprecedented proportions.[1]

This is a theme that runs through many government sources, with the secretary of defence in 1967 worrying that calling up more reserves might lead to “massive refusals to serve, or to fight, or to cooperate, or worse,” and that “it could conceivably produce a costly distortion in the American national consciousness.” One radical anti-war activist, who was head of the MIT student body at the time, has commented that

[a] look at the Pentagon papers documentation of decision-making during the period, and at newspapers and the public record of Congress shows a remarkable fact. Whenever some politician changed from voting pro-war to voting antiwar, or whenever some corporate head went on record against the war, the explanation was very nearly always the same. It was almost never the loss of American soldiers or Vietnamese soldiers or civilians, or the economic dislocations of the poor at home that provoked the new view. When elite figures announced their switch from hawk to dove, and when the Pentagon Papers listed factors assessed in choosing policies, the focus was always the desire to keep down the cost of political resistance.[2]

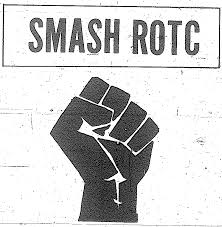

In the case of Vietnam, the growing movement did more than “send a message” to the authorities – it directly challenged power. As just one example, the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) supplied half the officers for Vietnam from colleges and universities around the US. Radicalized students threw a spanner in the works, using tactics ranging from patiently building up support in educational meetings to more confrontational methods. Between 1966 and 1973, enrollment was more than halved, and the ROTC failed to fill its quota [3]. Across the U.S., activists called rallies, burned draft cards, picketed recruitment centres, aided antiwar soldiers, and shut down campuses and workplaces, while the soldiers themselves ran antiwar newspapers, refused orders, went AWOL and more. Moreover, the accelerating spread of active dissent, and general distrust for “mainstream” politics, was a real worry for those in power. It threatened to fuel further unrest in the cities, which had already seen massive clashes bought on by anger at the slow pace of civil rights reform, and the lack of investment in communities. Learning from other examples around the world, elites understood that ignoring such a tide of outrage might destabilise the entire political system and lead to even more radical change.

The same broad picture emerges from the history of campaigns for the 40-hour week around the world, women’s liberation, civil rights struggles in the U.S., labour rights in the UK, and many other movements [4]. No such campaign ever got what they wanted just by asking politicians. Infrequent elections with no active discussion and participation leave democracy buried six feet deep under a pile of money – just where privileged minorities want it. To succeed, these movements had to challenge the interests of the powerful groups and systems that were causing their problems. They had to demonstrate that they could increasingly disrupt elite interests, and credibly threaten to do more, to the point that elites decided that they had to give in.

In contrast, between 1 and 2 million people marched in London on 15 February 2003 [5]. This was more than in any anti-Vietnam protest in the US, where demonstrations before the war began were minuscule in comparison. Many were under the impression that “telling Tony Blair what we think” in one day of action would sway the resolve of the government. While the effects of the march shouldn’t be underestimated (and sources on internal government discussions are not yet as complete as those we have in the case of Vietnam), it is certainly the case that the vote in Parliament went through as planned and sent the UK to war.

Elites evidently did not care about any moral appeal, as long as they could hope that the large numbers would not be galvanised into a continuing and growing movement that posed a real threat to their power. After being drawn into action on the basis of stopping the war before it began, many found this disheartening. But this says less about activism in general and more about mistakes made in this case. Most of all, it highlights the need for continuing efforts to grow in numbers, knowledge and commitment, and the readiness to impose real costs on elites through robust, active resistance.

Radical is reasonable

Criticising capitalism as part of opposing war is seen by some as a mistake or a distraction. The same could be said about linking to issues of racism, state authority and sexism. However, there are good arguments that (a) growing radicalism in the antiwar movement scares those in power, which helps to win our demands, (b) linking to other problems helps to broaden support for the movement, and (c) understanding the deeper problems causing war and imperialism helps us to combat the war, as well as the causes.

The quotes above drive the point home that one of the major worries for state planners during Vietnam was growing disaffection with politics as usual – their concern was that antiwar activism was driving people towards a radical standpoint on issues of economy, politics, race and gender, which more effectively challenged their power.

Within the antiwar movement, it was quickly found that organisations with sexist internal structure were less effective. To name one obvious reason for this, they could not retain women as activists. Indeed, these concerns contributed to the formation of second-wave feminism as a new movement in its own right [6]. Conversely, the broadening of the concerns of the civil rights groups to include war brought about many of the early gains for the anti-Vietnam movement [1].

We argue that capitalism propels corporations to seek profit with no regard to the consequences. It compels them to obsessively seek out more markets, labour, resources, and outlets for excess investment, wherever they can be found at the least cost. It propels these organizations into positions of massive, unaccountable power and creates a class of owners and corporate directors with interests opposed to those of the 99%. Political parties find it difficult to survive without the support of these people and organisations. This helps us to understand the causes of war and stops us from making naïve judgment calls about the likelihood of achieving victories by doing no more than holding demos and making moral appeals. Our concern about bureaucracy also helps us to understand why even anticapitalist political parties, with their permanent party jobs and comfortable connections to union bureaucracy, will be timid about supporting direct action in case the state’s response damages their position, and will often ignore the lessons of history to lead protests into ineffective dead-ends.

Based on cases like the Vietnam struggle, where the radical wing of the movement was crucial in building up a credible threat to power, we think that these understandings help rather than hinder the fight against war. Our hope is that we can convince others of this view, and that more people will support our actions in the coming months.

[1] People’s history of the United States, Howard Zinn, Harper Collins. Page 500.

[2] Fanfare for the future, Michael Albert and Jessica Azulay, Z books.

[3] See [1], p.491.

[4] See the other references and book lists and links elsewhere, and, e.g., The Making of the English Working Class, E.P. Thompson, Penguin; Remembering Tomorrow, Michael Albert, Seven Stories Press.

[5] The march that shook Blair, Ian Sincliar (Ed.), Peace News Press.

[6] The Feminist Memoir Project: Voices from Women’s Liberation, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Ann Snitow (Eds), Rutgers University Press. Of particular relevance is Meredith tax on the Bread and Roses group. See also Remembering Tomorrow, [4].

[7] Some very well-documented examples of the links between capitalism and the militarism of the NATO powers can be found in Killing Hope by William Blum. For example, he documents how the United Fruit company was incensed by some mild land reform processes in Guatemala and other reforms that threatened to bite into their profit margins. They successfully pressured the US government to act, aided the 1953-1954 CIA coup, and took independent subversive action of their own. Among several interlocks between government and this company, a former director of the CIA was later named to the company’s board of directors. We see the same patterns in dozens of cases stretching through modern history. (See also Bitter Fruit: the untold story of the American Coup in Guatemala by Stephen Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer for a longer account of this particular incident with a detailed list of references to released government documents and other sources.)

Pingback: Mob Rule vs. Democracy | Stop NATO Cymru