‘Educate, Cull, Disturb’

The following article was written by a Three Counties Sab in Autumn 2016. Feel free to use it, but please credit us as a group and please ensure that if you take any bits out of the article, it does not change the meaning of the words – it is important not to put out false information accidentally. Thanks!

Quite a few groups have written their own articles and information about cubhunting and we have our own aspects which we want to focus on in a particular way. Groups such as Hounds Off and the League Against Cruel Sports also have some good information, as do a number of books written by foxhunters, some of which we will be quoting in this article – it seems that the best way to learn about a subject is to learn about it from those who are most passionate about it and, when having to explain to police or members of the public what is going on during a hunt, it’s always good to have the support of books written by hunters themselves!

What is it?

Cubhunting, traditionally sometimes (and these days most often) referred to as ‘autumn hunting’, sometimes ‘cubbing’ though many well-known and historic foxhunters detest the slang. Hunts may say that they are just exercising the hounds which they do with the pack prior to cubhunting – often without horses, often on bikes. Other hunts may say that they are trail-hunting.

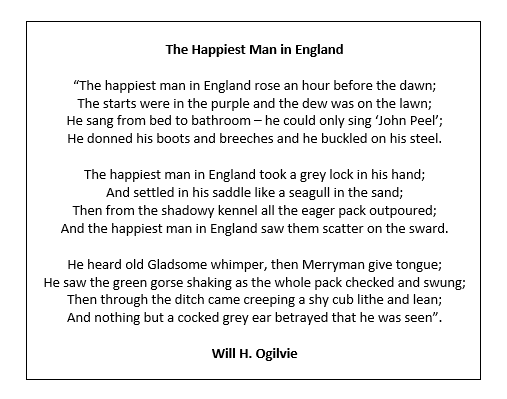

Picture shows the North Cotswold Hunt out exercising their hounds on bikes in August 2016, prior to beginning cubhunting

‘Trail-hunting’ is an activity that many foxhunts now say they are involved in since the Hunting Act came into force in 2005, where a false scent is laid on the ground for hounds to follow. This is not the same activity as ‘drag-hunting’ which dates back to the late 18th / early 19th century.

Cubhunting is “the pivot on which a pack of hounds revolves. It is no exaggeration to say that during the cubhunting season a pack is made or marred” [1]. It is an extremely important part of foxhunting, the reasons for which are explained later in the article.

When does it take place?

There is no set date for the opening of the cubhunting season but it “lasts, roughly, from late August or early September to the first week in November” when the main season starts [2]. If a hunt or local farmers believe that there is a large fox population ‘needing’ to be drastically reduced, the Master is likely to start as early in the hunting year as possible – as soon as there is no danger of hounds running into standing hay or corn – hunts will wait until after crops are harvested in their areas. “I begin to hunt with my young hounds in August” [3]. “We always start the moment the state of the harvest allows and continue almost daily” [1].

Cubs are usually born during the months of February, March and April, so will be about six months old by the time cubhunting starts and will be about adult size – adult foxes are also hunted during cubhunting. The term ‘cub’ is used to refer to foxes hunted up until the beginning of the main foxhunting season – see our Glossary page for more information.

“Cubhunting is a break-of-day affair… as the year gets older and cooler, so the Meets can be made later”. The day starts early (about 6am initially, gradually getting later as we get closer to the main season) as “… every advantage is taken of the cool of the morning for hunting – both for the sake of the hounds’ health and comfort, and because scent usually vanishes when the sun gets up” [2]. Scenting conditions are much better when there is still some dew or morning mist around – sun is a deodoriser and will evaporate scent as it warms up the ground. Mid-October meets may be held around 9am or 9.30am, but all hunts will do things differently [4].

Some meets are also held in the cooler hours during late afternoon and evening, it isn’t always an early morning event – we attended a cubhunting meet one morning in 2016 then got called out later in the afternoon to another meet for a different hunt!

What is its purpose?

The main reasons for cubhunting are:

• EDUCATION – teaching new hounds how to hunt as a pack and about their quarry

• KILLING FOXES – an essential part of the training is learning how to kill, getting a taste for blood and, of course, culling the fox population at the same time

• DISPERSAL – cubhunting will disperse family units of foxes in coverts and educate foxes to run into the open

The Masters will not be prioritising the entertainment of the field (mounted riders) and supporters – traditionally at many hunts supporters would ask permission of the Master to attend, though some meets these days attract larger numbers of riders.

Cubhunting is also a good time for the hunts to find earths (and badger setts) that will ‘need’ to be stopped later in the season.

Education:

“The killing of cubs is not the sole object of cubhunting… it is hardly even the primary object…” [2]. The “primary objective is to teach young hounds to hunt” and “to complete the education of the last year’s entry” [4].

The new hounds need to be taught patience and obedience (they are often ‘coupled’ to older hounds for some time) and to ignore distractions, such as non-target animals (deer, etc.).

Killing:

While hunts obviously want to kill and often want to ‘cull’ the fox population in the areas they hunt in, they also, of course, need to leave some foxes to hunt later on in the season, so they don’t want to kill all of them in an area and, when hounds do kill, it should be a good education for them as well.

“One well-beaten cub killed fair and square is worth half a dozen fresh ones killed the moment they are found… it is essential that hounds should have their blood up and learn to be savage with their fox before he is killed” [1].

That said, killing is an essential part of the education of the hounds, getting them used to the taste of fox as well as the sight and smell of them. Fuss should be made when a fox is caught, using correct horn calls and lots of praise [4].

Dispersal / education of foxes:

“After 1st November the subscribers… will want their money’s worth in the shape of galloping and jumping”. This brings in the “third object – the education of the foxes. By nature a fox is a creature of the woodlands and coverts… we foxhunters want a gallop over the open country if we are to enjoy ourselves fully. So foxes are hunted in covert when young; thus they come to think – quite erroneously – that safety lies in flight. Beside that, cubhunting splits up the litters; there are few things more annoying, during the regular season, than to draw covert after covert blank, and then to find three or four foxes all in one covert, hounds become split up, it is impossible to get them away on a fox… cubhunting tends to prevent that, for the cubs decide that their home covert… is no longer safe to hold them” [2].

What does it entail?

“How the cubhunting is conducted will depend to a certain extent on the type of country, but there are certain basic principles that are universal” [5]. Early cubhunting may take place in coverts which are close together (“it is an old maxim that hounds should not see daylight for the first month of cubhunting” [5]), so that any runs are short with cubs just ducking into the next covert. Whippers-in should be posted at either end of the covert, the huntsman riding up to the covert, encouraging the hounds to enter. Older hounds should be used to this and fan out with some of the younger ones going with them. The huntsman should reassure the hounds that he is there, but not interfere too much as too much noise will raise their heads – hounds should be allowed to use their initiative and natural skills [4].

Some hunts, however, rely heavily on ‘holding up’, especially early on in cubhunting, as seen in this video of the Cotswold Hunt in September 2016

“The system known as ‘holding up’ is reported to during the first half-dozen weeks of cubhunting. The coverts are surrounded by the Hunt staff and the Field and any cubs which attempt to break away are headed back”; “to hold up a covert is to surround it with riders and foot followers so that cubs cannot escape during cubhunting” [2]. The ground is often too hard after the summer to keep up with running foxes and more cubs are killed by stopping them from escaping.

“The racket we raise seems effective. Not a hard-pressed cub essays the gap and, the din fading to the far end of the covert, we sit back satisfied with the results of our vigilance” [6]. If you watch the video of the Cotswold Hunt linked to above, Guy Wheeler could easily be describing that meet in his comment.

Some, like Michael Clayton in his book ‘The Chase: A Modern Guide to Foxhunting’ [4] warn not to rely too heavily on ‘holding up’ and perhaps only to use it for a short time until old foxes and one or two determined cubs have made a break for it. Sir Peter Farquhar believed it shouldn’t be done as hunts want foxes to think that safety lies in leaving covert and not hiding up in them. It is also not good for the hounds as the noise brings their heads up (as they hunt by scent, they should be keeping their noses to the ground and not relying on supporters to indicate where foxes have run) and it can make them lose concentration.

“Though the ground was dry and hard for cubhunting, scent was good and hounds could generally run hard, and killed their cubs without much help” [7]. “Foot followers must be prevented from ‘mobbing’ a fox by driving it virtually into the hounds’ mouths with over-enthusiastic shouting and brandishing of sticks” [4]. “The only noise you want to hear out cubhunting is the cry of the hounds. It is not an occasion for a trumpet voluntary with choral backing. I went cubhunting once with a pack of hounds where the holloaing was continuous. The huntsman spent the morning tootling and galloping from screech to screech, trailing crowds of wildly excited young hounds. The old hounds sat in the rides and scratched, and I imagine that the foxes went back to bed” [4]. Again, this last quote by Michael Clayton could easily have been describing the Cotswold Hunt again. Not all hunts use holding-up as a tactic – if you see them doing so it’s a pretty good indicator that they’re not following a trail but don’t assume they’re not trying to kill foxes if they’re not doing it! It’s pretty clear, however, what the intentions of the North Cotswold Hunt are in this video…

Some sources, such as Michael Clayton and John King in ‘The Golden Thread’ [1] say that it can be good to draw through and draw back through coverts to try and re-find tired cubs who are laying up in thick undergrowth, staying in the same coverts all day to get all the cubs rather than stirring up a fresh litter when hounds are more tired. Charles Frederick states that “it is quite a good principle not to try and cover too much ground in a morning’s cubhunting. It is better to concentrate on one litter, and educate them properly” [4]. However others suggest just stirring up the area and not drawing the covert too thoroughly, dispersing some foxes to other coverts and leaving some.

“During the second half of October hounds may be ‘let go’, and you may get a short hunt or two in the open”.

Marking to ground and digging out

“It is equally disappointing if a fox runs to ground just as hounds are settling on to the line” [1] just like in this video from the North Cotswold Hunt in September 2016 where hounds pick up then almost immediately take interest in a hole sabs believed a cub went to ground in.

Dig-outs may occur during cubhunting if foxes do go to ground – the Duke of Beaufort in 1980 wrote that “digging out a cub is a matter of policy in the education of the young entry, and the cub should be dug out and eaten by the hounds”. The hounds will learn how to ‘mark to ground’ at this point, indicating that a fox has sought shelter below ground [8]. Dig-outs also encourage patience and discipline [4].

At a cubhunting meet, you’re likely to see far fewer supporters (on foot and on horseback) than during the main season and hunt staff are less likely to be wearing the traditional ‘red (pink) coats’ and instead most wear ratcatcher (tweed).

You may see riders and other supporters surrounding rough bits of land, beet fields, small coverts (woods, etc. where foxes could be hiding up) and perhaps making a lot of noise.

Cubhunting in some areas is different – there seem to be different versions of it in places like Exmoor and the Lake District. Some hunts which are not traditionally foxhunting packs, such as Harrier packs, may also have their own version of ‘Autumn hunting’. The Ross Harriers, despite their traditional quarry being hare, also hunt foxes so they will be seen cubhunting prior to their season starting.

What do sabs and monitors do?

“… much good work can be undone in a short space of time” [5] and cubhunting is a vital time to start sabotaging the hunts’ attempts to get the hounds used to the taste, smell and look of foxes. “It is impossible to over-emphasise the importance of the cubhunting in the making of a pack of hounds” [4].

Therefore, we try to get out to as many cubhunting meets as we can, getting the hounds used to our voices, horn calls, rating (telling off) and, of course, trying to stop them from killing, both for the foxes trying to escape on the day as well as making them a less efficient pack for the remainder of the season.

In Three Counties Sab group we tend not to use the word ‘save’ when talking about our activities. This is because, unless we actually pull a live fox from the jaws of the hounds, some foxes are able to escape without our interference, others gain a few extra valuable seconds when we help (not save) them by covering the line of their scent with citronella or distracting hounds with horn calls or holloas. The first thing we have to be careful of during cubhunting is not becoming just another foot follower, another presence making noise and stopping foxes from being able to escape.

“I turn to ride the fifty yards back to my chosen station… when, into the thorn frame of a further gap… a fox… I ram the mare into a canter and roar like a bull but the fox stands its ground… two cubs whip out of the middle gap, across the road”. A vixen who “has got a man exactly where she wants him… slides silently back into the undergrowth, to rescue the rest of her litter from the hounds” [6].

Glossary:

Blank: to draw blank is to fail to find a fox

Check: when the hounds lose the line

Couple: a ‘couple’ means two hounds. Couples are also two collars linked on a chain

Covert (pronounced ‘cover’) is a patch of woods or brush where a fox may be found

Cry: the sound made by hounds hunting

Cub: a young fox

Double: to blow a series of short, sharp notes signifying a fox is afoot

Draw: to search for a fox in a covert

Entered: an ‘entered hound’ is a hound that has done a season’s hunting

Field: the mounted followers

Foil: any smell or disturbed ground which spoils the scent line

Ground: “to go to ground” is to take shelter in a hole (badger sett, fox earth, etc.)

Head: to head a fox is to cause him to turn from his intended direction of travel

“Hoic holloa”: when the huntsman has heard a holloa but needs to check the direction he shouts “Hoic holloa” and the you should then holloa back to him

Holloa: a shout to indicate to the huntsman the direction in which a fox has run

Line: the scent left by the quarry

Mark: a hound “marks” when he indicates that a fox has gone to ground, stopping at the earth / sett, tries to dig his way in and bays

Quarry: the fox or other animal being hunted

Rat Catcher: a tweed jacket worn during Autumn Hunting

Rate: a warning given to correct the hounds

Riot / rioting: when hounds hunt something other than their intended quarry

Scent: the smell of the line

Speak / speaking: hounds do not bark, they ‘speak’ when they are hunting a scent

“Tally-ho”: yelled by someone who spots the fox being hunted so that the huntsman knows where the fox has run e.g. “tally-ho back”

Walk: hounds at walk (also known as puppy walking) is where whelps are sent to private homes from the age of about 8 weeks until they get too big and boisterous for the walkers and are returned to the kennels to learn how to fit in with the pack

Whelp: a new born hound before it comes back from walk

Books used:

1. ‘The Golden Thread’ (1984) by Michael Clayton and John King

2. ‘Introduction to Foxhunting’ by D. W. E. Brock (Master of Foxhounds)

3. ‘Thoughts on Hunting’ by Peter Beckford

4. ‘The Chase: A Modern Guide to Foxhunting’ (1987) by Michael Clayton

5. “Autumn Hunting” (article in ‘Hounds’ magazine, October 1986) by Charles Frederick

6. ‘The Year Round’ by Guy Wheeler

7. ‘The Heythrop Hunt’ (1st ed., 1935) by G. T. Hutchinson

8. ‘Foxhunting’ (1980) by the Duke of Beaufort