The following article was written by a member of Three Counties Sabs in Summer 2016

What is terrierwork?

“First and foremost it is a form of pest control” according to the National Working Terrier Federation (NWTF) which “assists in proper management of quarry species”. The Masters of Foxhounds Association (MFHA) state in their article ‘Methods of fox control (pre-ban)’ that is “mostly used in response to specific local predation problems” where hunting and shooting are not suitable or practical and where a specific fox is being targeted. Picture credit tbc-photography / 3C Sabs

Terrierman David Harcombe describes terrierwork as “a worthwhile field sport” in its own right. Whatever the main purpose is of terrierwork, terriers have natural instincts to hunt and seek out and pursue animals which humans tend to see as ‘vermin’ – foxes, squirrels, rabbits, rats, even badgers. Once the fox, for example, is found, the terrier’s role is not usually to fight with or kill him, but to bark continuously at him to either flush him from hiding or to draw him out or to keep him at bay, guiding the terriermen to his location.

“Until very recently [barking] was an essential quality in any working terrier in that it was the only means by which it could be located underground or in dense cover” (before locating equipment was developed for use) – NWTF information. So much so that “those who showed no promise and were unreliable were put down or drafted to suitable homes” (‘The Gaffer’, Hounds magazine, September 1987: “Working Terriers and Terriermen”).

Rules of hunt terrierwork are set by the NWTF and the MFHA, though parts of these sets of rules will have been superceded by the Hunting Act 2004. For example, one rule is that care must always be taken to minimise the risk of injury to both the quarry (hunted animal) and the terriers.

The NWTF

Founded in 1984, the National Working Terrier Federation represents practising terriermen, professional and amateur (voluntary) – landowners and farmers, gamekeepers and hunt terriermen, land and wildlife managers.

The MFHA

The Masters of Foxhounds Association is the governing body of foxhunting and represents 176 packs of foxhounds in England and Wales, plus a further 10 in Scotland. They have written strict rules and codes of conduct to ensure the highest standards of practice which all member packs have agreed to abide by. The MFHA have a number of sanctions available to them if hunts are found to not be adhering to these rules and codes. They advise members on how to hunt within the law whilst campaigning to have the hunting ban repealed.

Links with hunting

In Hounds magazine in September 1987, ‘The Gaffer’ writes “that a great deal of sport depends on him” (the terrierman) with the Wildlife Network arguing that if terrierwork were to be banned “hunting would be seen by many farmers… as next to useless as a form of fox control” in their literature ‘Putting the fox first’. The MFHA, however, states that “terrierwork is not part of the sport of foxhunting” and that it is carried out as a “fox control operation” solely at the request of farmers or gamekeepers. In his book ‘Diary of a Foxhunting Man’, Terrence Carroll writes that “terriermen are the unseen – or seldom seen – side of hunting… they seem humble and scruffy alongside the splendour of the Huntsman and Whippers-in but they are a vital part of the Hunt staff”.

Prior to the hunting ban, if a fox was run to ground it would be up to the Master of the hunt to decide what to do about him, taking into consideration the wishes of the relevant landowner/s (e.g. kill the fox / move him to another location / leave him alone) and that if the fox were to be killed, it must be done humanely. Many packs started this way, going out at a local farmer’s request when a fox had killed livestock.

“When being chased by hounds, a fox will often attempt to escape underground. At this point a terrier is often sent down the hole to hold the fox at bay while the terriermen dig out the fox” (League Against Cruel Sports report (2010) “Hunting with Dogs: Past, Present but No Future”, p.12).

‘The Gaffer’ in his article links hunting and terrierwork again, saying that if, after a hunt “hounds catch their fox or mark to ground, then the terrierman is quickly on the spot” to use his terriers or to clean up. An interesting historical book by Sean Frain about William Irving (who was a Lakeland huntsman and terrierman earlier on in the 1900’s) certainly seems to show that terriers were used to flush out or kill foxes on the majority of days when the hunt went out. There seems to be somewhat contradictory information, even prior to the ban, of who the terriermen are, what their role is in regard to hunting and why.

The situation since the ban on hunting with dogs

“The adoption of trail hunting in the wake of the hunting ban has made the role of the terrierman redundant in some places” (“Presenting the Patterdale Terrier”, countrylife.co.uk). In the Horse and Hound online forums in 2012, ‘Dovorian’ asks the role of the terrierman and the terriers “under the current regime”. A few answers were given about different packs having different reasons, that terriermen can still do legal terrierwork and fox-control for farmers (which wouldn’t require the involvement of the hunt, of course) and that some terriermen carry around the artificial scent and quite often lay the trail for foxhunts who are now trail-hunting (which wouldn’t require them to have the terriers with them, of course).

The Law

The Hunting Act of 2004 is seen by many on all sides of the argument as a pretty badly-written piece of legislation, the purpose of which was to ‘make provision about’ the hunting of wild mammals with dogs and to prohibit hare coursing. There are exemptions included in the legislation, one of which is known informally as ‘the Gamekeeper’s Exemption’ and, formally, ‘Use of dogs below ground to protect birds for shooting’. This exemption allows someone to use one dog underground to flush out a fox to a competent person with a gun. It can be used in the way which the NWTF and MFHA talk about terrierwork – when there is a problem with a particular fox in an area and there is a ‘need’ to get rid of the fox in order to ‘preserve’ game / wild birds so that they can be shot. Many parts of the Hunting Act have not yet been tested in court – the use of spades, for example, as well as whether one could use the exemption while out as part of the hunt on the day.

Various police forces (or some officers within them) have agreed with our interpretation of the law (or have come up with the same interpretation independently) that if you are out as a terrierman with a hunt, you are at that time part of the hunt and not acting as, on or behalf of, a gamekeeper. To clarify, if there are pheasant pens in an area and a fox living nearby keeps killing the poults, it is that fox which the exemption exists for, so that you can deal with the specific issue you have. If a hunt is in an area and (intentionally or unintentionally) gives chase to a fox, especially if the hunt lasts a long time or covers a lot of ground, and the fox goes to ground in an earth near to the pheasant pens, how can you guarantee that the fox you’re flushing and killing is the one killing the birds?

The following video was filmed by League Against Cruel Sports investigators in March 2014 and shows the Lamerton Hunt chasing a fox before terriermen arrive on the scene and later reappear from the woods with what appears to be a live fox cub. When investigators then went to find the earth, they found it had been dug-out, a dead cub lying beside it.

Back to Willie Irving, apparently he “was passionate about the natural cycle and wouldn’t dream of taking a litter of cubs for no good reason… he was certainly a good example for any who hunt foxes today… where livestock is being worried… even then it is important to try and exterminate only the guilty party”. The exemption is, unfortunately, used as an excuse for flushing foxes to the hounds and for dig-outs up and down the country.

As an example, despite the fact that there were no game birds in the area and the hunted fox had sought shelter, after a long chase, in a badger sett (protected under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992) the terriermen employed by the Ledbury Hunt at the end of the 2014 – 2015 season attempted to dig the fox out using a terrier, a locator and spades. No gun was present…

The terriermen, pictured, tried to tell members of Three Counties Hunt Sabs that they were not part of the hunt and that it was a rabbit warren, but also asked us to stop filming while we were talking. Picture credit tbc-photography / 3C Sabs

For more information on the Hunting Act exemption for gamekeepers, what the law states can and can not be done and why it is a choice between using a terrier and using spades (not both) when after a fox underground, check out our page on the exemption.

Artificial earths, badger setts and more ‘unofficial’ roles of the terrierman

Groups like our own – Three Counties Hunt Sabs – are well aware of the extra roles that terriermen (and, indeed, other members of hunt staff) have taken on both in traditional hunting and since the ban. ‘The Gaffer’ writes that “if the earth-stoppers do their job well it makes life much easier for the terrierman, as then he only has to check certain places in the morning to make sure they have not been… opened”. The role of the earth-stopper is to block up holes like earths in order to prevent the hunted animal from seeking shelter in them. In our experience, this still goes on and continues to include badger setts, terriermen often very involved in this role.

Sett-blocking

“Badgers… you may stop them in, but you can’t stop them out if they wish to get in, which is why big badger earths are such a nuisance in a hunting country…” (from ‘Hunt and Working Terriers’, Jocelyn Lucas).

In our article ‘Hunts vs Badgers’ we write in more detail about incidents of sett-blocking by hunts. Earth-stopping / sett-blocking has been part of hunting for hundreds of years, badgers even being described as vermin for interfering with a good hunt for having large setts with complex tunnels. “Successful hunting depends very largely on thorough earth-stopping, which means blocking foxes’ dens while they’re out… so they cannot duck back in” write Terrence Carroll in ‘Diary of a Foxhunting Man’. He describes the practice as “murky work that used to be carried out at night by men whose social status was only a notch above poachers… hunts would often fine them if a fox managed to get into a hole that should have been stopped” and that “terriermen often double as earth-stoppers and in any event are closely associated with them”. With badger setts being more complex than earths, they’re even more likely to be stopped. Additionally…

“Badgers underground can present great challenges to terriers, and will fight ferociously. Foxes have been known to hide behind badgers in an earth, leaving the badger to face the terrier” (Sean Frain’s book on Willie Irving again).

This is backed up by the Duke of Beaufort in the book ‘Fox Hunting’ who speaks of the ‘old days’ when “many countries used to pay an earth-stopper a regular salary, and then fine him half-a-crown each time a fox went to ground in a known earth”. His earth-stoppers would have an annual feast in Badminton (he would lead the singing) then they would be “presented with a fee on the production of their pile of earth-stopping cards”.

The article ‘Beware Brock’ in ‘Hounds’ magazine from November 1990 (p.24) concerns the plight of the earth stoppers and terriermen. Jem Hills, a previous huntsman of the Heythrop Hunt, writes about badgers… “I killed nine badgers the first season I came here, & some of them with terriers. Once I turned one out in the frost with a couple of my terriers, Cribb and Fan… they held him till I walked a couple of miles and got a sack…” Of course badgers are now protected under law regardless of the hunting ban. This didn’t stop the Atherstone Hunt terrierman blocking this sett, filmed by West Midlands Hunt Sabs, on Boxing Day 2014…

… or this (unidentified) man blocking a sett a field away from a Heythrop Hunt meet just hours before the hunt arrived (filmed by independent Hunt Monitors).

‘Bagged foxes’

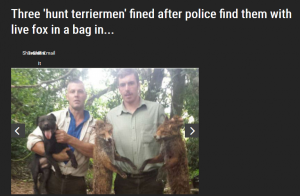

Other roles of the terriermen may include ensuring that there is ‘sport’ for the hunt, that areas which have a smaller population of foxes are ‘re-stocked’ so that it is more likely the hounds will pick up on a fox or that the hunt have a fox ready in case the day is otherwise ‘blank’ (when no scent is picked up on by the hounds). This is known as the use of ‘bagged foxes’ and is suspected to be the reason behind the Ross Harriers hunt terriermen being caught with a live fox in a bag and terriers in the middle of the night – obviously not flushing to a gun…

An “animal becomes “captive” if restrained in any way” and the Protection of Animals Act 1911 is to be observed (“Hunt Terrierwork Code of Conduct”, MFHA).

In “Methods of fox control (pre-ban)” the MFHA state that “the fox is always hunted in territory with which it is familiar. It will know where to go to give itself the best chance of escape”. This video shows a joint meet between the South Herefordshire Hunt and the Crawley and Horsham Hunt in Herefordshire in December 2015 where it is suspected that a bagged fox may have been released. He was seen by another group running with his brush and his head up, signs that he did not know where he was or where to go to escape the hounds, whilst members of Three Counties witnessed men walking away from the area with cable ties in hand and what they thought was a sack under a jacket.

“In those days [the 1920s] cubs were often dug out, raised and then sold, often for the sake of restocking a hunt country that had been depleted by diseases such as mange, or distemper, or possibly over-shooting by keepers. Many country periodicals carried advertisements for foxes for sale. Finding, digging out and selling cubs could be quite a prosperous sideline for anyone who was in need of a spare few quid”. (‘Willie Irving: Terrierman, Huntsman and Lakelander’, Sean Frain, 2008).

In May 1980 a League investigator filmed Chris Wood, of the Holderness Foxhounds, and others digging 4 fox cubs out of their earth and, the League claim, then put into an artificial earth for hunting. Thanks to AWISACIG for putting up ‘Calendar’, a Yorkshire ITV report, from 1983 which shows the footage and following interviews.

Artificial Earths

“In countries where earths are scarce it is sometimes found necessary to make artificial earths, to provide somewhere for local foxes to have their cubs… [my grandfather] felt that artificial earths should be primarily intended as breeding establishments” (Due of Beaufort in his ‘Fox Hunting’ book). “It should be bourne into mind that an artificial earth is frequently the means of introducing mange into a country”.

For more information regarding artificial earths, check out our specific page dedicated to them.

“Foxes are lazy diggers” and tend to enlarge rabbit holes or use badger setts or man-made structures such as drains, hay-bale stacks and piles of rocks (‘Methods of fox control’, NWTF). Artificial earths can be put in areas in order to encourage foxes to live in them, the excuse being that they are then easier to find if they are causing trouble in an area, though the NWTF state that experience has shown that those which do the most damage tend to be the easiest to locate anyway (via trails of feathers, for example). So why are AE’s used by hunts? They are easy places from which to find and bolt foxes (as well as using them to encourage fox-breeding in the area)… they are even known to house badgers – many are big enough.

“When the hunting season finally peters out and there seems nothing to do I try to put in a decent artificial if I can” (J. Darcy, “Drains” article in ‘Earth Dog – Running Dog’ magazine, issue 238, May 2012). “I have had the privilege of working a great many [drains] over the years… old land drains to stone culverts to artificials”. Terrierman David Harcombe (in his book ‘Badger Digging with Terriers’) says that terriers should be on leads when not working, but Oscar Bates from the Ledbury Hunt claimed that his terrier, Nel, had run into a drain when he let her out for a wee in part of this video, coincidentally marking a fox in the very same drain. Perhaps he should have taken his fellow terrierman’s advice regarding leads.

“I known some scoff at working drains, but many an otherwise blank day has been saved by working them” says J.Darcy again in the same article. A ‘blank day’ or ‘drawing blank’ is when hounds have failed to find another scent. In some countries “favourite coverts are so bare after Christmas that they seldom hold a fox. Such country may be opened up by the construction of an artificial earth… an additional advantage is that if an artificial earth is left open, it will only take a few minutes to bolt a fox… if it is a blank day, one knows where to go with some certainty of finding a fox” (The Duke of Beaufort, once again).

A recently-released (June 2016) expose of the Pytchley Hunt, footage handed to the Hunt Saboteurs Association, includes the use of AE’s and, in late 2019, the Kimblewick Hunt saw two members convicted for dragging a fox from an AE and throwing them to hounds.

These pictures are of a well-maintained artificial earth right by woods containing pheasant pens at a shooting estate in Gloucestershire. The Ledbury Hunt are allowed to hunt right through the estate come the end of shooting season in February and sabs have caught members of the hunt lingering around the artificial when no other scent has been found by the hounds.

Towards the end of the 2015 – 2016 season, terriermen from the Ledbury spotted a sab keeping watch on the AE then rapidly reversed away. Like the rules say, ‘do not run away if challenged’ (if you’re doing nothing wrong…). Photo credit 3C Sabs.

In their own words

April 2012 (7 years after the Hunting Act came into force) saw the 237th edition of the magazine ‘Earth Dog – Running Dog’ sent to its subscribers. David Harcombe, terrierman and editor of the magazine, authored an article entitled “Something Special Happens”. Some of the more interesting bits of the article include:

– “working animals [hounds, terriers, etc.] have this inbuilt ability to ignore instructions, they become deaf to suit their own purpose”

– “the hounds hunted away [unintended by the hunters, of course!] and eventually were found to be marking to ground… we entered Roxy at the main mark”

– “both days started out as exercise but both showed fine hound work when the pack proved they had a mind of their own and started ‘doing what comes naturally’…”

– “in action at the next meet”

– “they brought a fox down [a mountain]… after a really fast hunt and put it to ground across the valley”

Mr. Harcombe talks a lot about being at hunt meets and being called ‘to a mark’ repeatedly. He tries to explain hounds hunting and marking to ground as just what they do naturally and that any such hunting that he refers to was not intentional on the part of the human hunters, therefore not illegal (there is no ‘recklessness clause’ in the Hunting Act). He covers this way of ‘careful’ writing in the following edition of the magazine, released in May 2012 in “Nothing to Write Home About” when he says that one’s intention must sometimes be explained more clearly since the Hunting Act came into force. The article, again, mentions hunt meets and dig-outs (all talking about the most recent season).

The article “A Certain Weakness” by Gordon Mason also links the hunting season and terriermen, as well as talking about dig-outs after the shooting season has ended. Granted, there is no ‘closed season’ on terrierwork, but if one is going to use the Gamekeeper’s Exemption in order to protect game birds for shooting, logic would dictate that it would be most sensible to do so mainly before and during the shooting season. “Foxes in the air and Hare to the ground” by Buster, in the April edition, also speaks of looking for foxes after shooting has ended.

“As shooting season ended for another season [in February] we were working through a large estate… and hounds were drawing through a wood quite close to the meet when I heard the boss blow two sharp notes on the horn. Not three for a mark, two means terriers. While working the drag we had laid, hounds had shown an interest at an earth on a bank so, while the hounds were taken away, we had to check it out while the keepers looked on with interest…”. “’What’s happening?’ asked the huntsman”. “I would have to go on, following the hounds with terriers in case of a call through the rest of the day… I asked the lads if they were ok to stay stay and sort it out… they were always anxious to get the spades out”. After all this, the fox was ‘accounted for’ hours later, just before the hounds marked again at another earth, which the terriermen then dug as well. And then another mark… (Gordon Mason’s “A Certain Weakness”).

We’re unsure how the guys went from laying the trail to following the hounds, but that aside, let’s believe Mr. Harcombe and Mr. Mason for just a moment, for the sake of this argument, and accept that the hounds in each of these accounts were in fact just doing their own thing and ignoring the huntsman’s instructions. Let’s accept that the human hunters had no intention to chase or put to ground any of the foxes involved. Or let’s say that the hounds were just ‘cold-marking’ without a prior chase. Aside from the fact that they’ve basically just stated that hunts cannot guarantee control over their hounds, there is no need to dig or bolt a fox just because hounds have marked him to ground, especially if the chase prior to that was an ‘accident’. Were any of the foxes referred to causing trouble in the area and, if so, can it be guaranteed that, say, the fox who was chased down the mountain and run to ground was indeed the one causing the problems? The authors of the article write as though there is no other possible option available but to enter a terrier once hounds have marked…

The NWTF ‘Rules of Terrierwork’ state that terrierwork is to provide a pest control service which is at all times selective. It seems like the terriermen choose to ‘select’ any fox which the hounds indicate to be in the area and not just those that have ‘worried livestock’. Again, from the book about Willie Irving: “it is important to try and exterminate only the guilty party”.

“If in doubt, keep your terriers out” (Rule 12, NWTF Code).

Our Experience

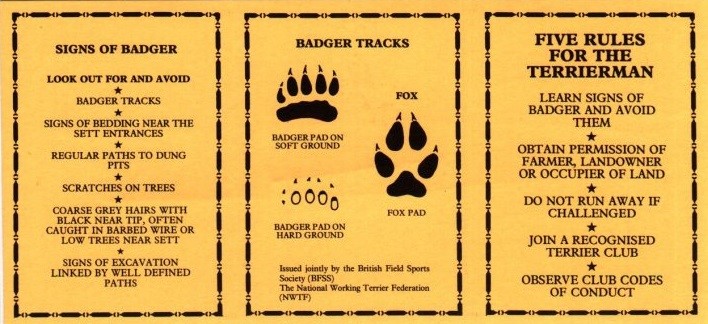

– “all excavations are to be back filled and the earth and surrounding area reinstated as close as possible to its original condition” – NWTF Rule 9

– Rule 3 of the ‘Five Rules for the Terrierman’ is “Do not run away if challenged” as “an innocent terrierman should have nothing to fear”. The following video shows the terrierman (and friends) from the Heythrop hunt leaving the area as a monitor from the independent ‘Hunt Monitors’ runs on to the scene, believing a dig-out to be in progress after the hunt had chased it into the area. Neither of the above rules have been adhered to here (this picture also shows the area)

Even terrierman David Harcombe says “it is a simple matter to leave a set in the same condition it was found and yet, surprisingly, you will sometimes encounter those who will not be bothered” on page 98 of his book ‘Badger Digging with Terriers’

– “terrierwork is limited by the fact that a large proportion of the foxes that are either run to ground, or live below ground seek sanctuary in badger setts”. Back to the Ledbury in Upton, we’ve already linked to this video and photos. Harcombe also talks about it being ‘distasteful’ to disturb a badger when she has cubs, so he advises not to enter terriers into setts after February… and yet we keep seeing this. Even a man who enjoys digging setts and earths speaks against such things…

“needless to say, terriers should not be allowed in earths in the spring of the year when cubs are young”

The Ross Harriers are another example of a hunt who have blocked / run foxes to ground in badgers setts – in this video, for example at an end-of-season meet

The NWTF claim that “terrierwork poses no threat to non-target species and disturbance to other wildlife is minimal, or non-existent”. For the sake of argument, let’s believe that the Ledbury terriermen in the video genuinely believed that it was a rabbit warren that they were digging. Let’s even accept that it was a rabbit warren for a moment, surely that doesn’t fit with the claim of the NWTF – any terrier entered would pose a threat, or at least cause a disturbance, to any rabbits in the warren. As it is, it was actually an active badger sett, so the badgers would have been at risk of disturbance anyway. David Harcombe (once again in the book about digging badgers) also suggests that “terriers should not be entered to a badger from, say December to May” due to the potential presence of cubs (p.20) as the mother might abandon them or ‘bury the cubs for safety’ which Mr. Harcombe describes as “distasteful”. The video was filmed at a hunt meet late in January 2015 and is only one of many incidents of terrierwork / digging out at setts that we know of, others taking place even later in the season (which finishes in early April in our part of the country).

We have somewhat less experience of terriermen ‘re-stocking’ the hunting country of foxes (if the country has few foxes then they will want to bring some in / encourage breeding by providing shelter – hence why some woods have traditionally been managed for foxhunting – and providing food). We know that it goes on, through the dumping of dead animals (illegal as well) such as sheep and hens in areas where there are earths / artificial earths and through procuring foxes from other areas – often gamekeepers will want foxes gone from near their pheasants or other birds kept for shooting but instead of killing them, they’ll pass them on to hunting friends and terriermen to ‘re-stock’ an area with.

“… he should know the exact whereabouts of each litter… when one district is rather short of foxes and another in the same hunt is overstocked, it is advisable to move a vixen with her cubs to some covert where there is no litter” (J. Otho Paget – ‘Hunting – notes on hunting the fox, hare, stag and otter’).

“… the appointment of careful earth-stoppers, as their duty extends to the taking care of the litters of foxes, as well as to the stopping of the earths” (‘Observation on Foxhunting and the Management of Hounds’ – Donald Cook).

Spades and the Law

The video also brings us on, very briefly, to the issue of spades and the law. The Hunting Act and Gamekeeper’s Exemption specifically does not mention them. That is to say that their use is not specifically prohibited, but they also do not feature in the specified criteria which must be satisfied for the exemption to be valid… The exemptions talk about what is allowed by law, not what is prohibited. Photo credit Sheffield Sabs – dig-out at Escrick Park, Nov ‘11

‘Use of dogs below ground to protect birds for shooting’

“The use of a dog below ground in the course of stalking or flushing out is in accordance with this paragraph if the conditions in this paragraph are satisfied”

The first condition is that the stalking / flushing is to prevent / reduce serious damage to birds kept or preserved to be shot. The second is that the person doing the activity has written evidence that the land belongs to him / he has permission to use the land. The third condition states the only one dog may be used below ground at a time.

Additionally, reasonable steps must be taken to flush the wild mammal from below ground as soon as possible once found and that it is shot as soon as possible once flushed and that the dog is under sufficient control so it does not prevent this.

So, surely this means that the animal must be flushed and shot. Not dug. And the dog must be under sufficient control (so it shouldn’t get stuck below ground and have to be dug-out itself). And a gun should be present (along with a competent person with a license to use it). This picture shows a Ledbury terrierman in 2016 and the young son of the huntsman, spades in hand, terrier by the side, a bag of nets and no gun (credit 3C Sabs)

The use of terriers is not the only way by which hunts can flush foxes from drains, etc. – we’ve also seen hunts using drain-rods. These are flexible rods which can often screw together to make them longer and are used to clear blockages from drains, therefore quite useful in scaring a fox out of his underground hiding place. Not so useful in badger setts and larger earths with more complex tunnels, but certainly a tool which you might spot being used at artificial earths or drains such as the one which Nel the terrier marked a fox in.

In this video, long wooden sticks where being used by the terriermen of the Duke of Beaufort’s Hunt in November 2016 as well as spades. We are unsure whether the fox had already been bolted from the AE (as hounds were heard soon after in full cry just a few fields away) or whether they were stopped mid-dig-out.

What do we do to stop the killing?

Step 1: Identify the terriermen

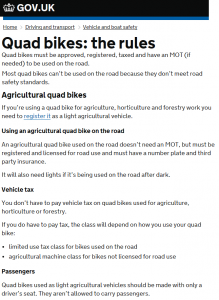

A common mistake made by many people is thinking that anyone out with a hunt on a quadbike is a ‘terrierman’. This is not the case, though we do have quadbike-riding supporters of hunts who assist in dig-outs, blocking setts and so on, for example with the Ledbury Hunt. Local landowners and other supporters may also follow the hunt on quadbikes and may not be any more involved with the hunt than a regular car supporter. It is important to be able to identify the terriermen from the hunt and to not get distracted by others, in the same way that you need to be able to identify the ‘important’ members of the hunt – e.g. huntsman and whippers-in – and not get distracted by anyone wearing a red coat.

We believe that terriermen can take many more lives during hunts than the huntsman and hounds do and that many kills by the hounds are often helped by the stopping-up of earths and setts prior to a hunt – meaning the fox cannot easily escape – or because the fox has been dug-out having sought shelter underground from the hounds. These two photos (3C Sabs credit) are of supporters of the North Cotswold Hunt giving one of the ‘Bicester Boys’ hunt stewards a ride (top photo) and of the Ledbury Hunt terriermen in the 2014 – 2015 season (photo right). A giveaway for a terrier quadbike is the terrier box, usually on the front with air holes in it, and the presence of terriers inside – some quads have storage boxes (sometimes carrying spades and nets, sometimes lunch).

Another mistake is thinking that terriermen have to be on quadbikes. Some of the hunts in the three counties do not have obvious terriermen. With some we can identify the men from previous seasons, but they do not seem to have any terriers / spades / nets / a gun with them). We’ve also identified regular supporters of the hunt who spend a lot of time with the terriermen and who we now know to be carrying ‘equipment’ around for them.

Step 2: Identify the signs

Hounds marking to ground: you may hear this when hounds are speaking and then seem to become stationary, but still making an excitable baying noise within a wood. If you can see them, they may be trying to dig into a sett or earth or scratching around it and baying or whining. If the huntsman is right with the pack and they are a tight pack, like the Ledbury Hunt, they may not be making much, or no, noise at all as the hounds know their master is aware of the mark. Remember that it doesn’t require the whole pack to give chase to or mark a fox.

Horn calls should also be listened out for – two or three short notes on the horn – as these calls mean ‘mark to ground’ and ‘terriers’ (i.e. asking for the terriermen to come to the mark with the terriers). However, we live in an age where technology is being used on a daily basis, even within the hunts – many ex-huntsmen and masters would be horrified as to the extent of this – and radios and phones are now also being used for communication between the huntsman and the terriermen.

Keep an eye on the terriermen if you can do throughout the day – they are likely to kill more than the hunt themselves, so use your discretion and, if suspicious, you might want to keep a closer eye on them than the hunt if there has already been a mark. A couple of seasons back, the Ross Harriers marked, a couple of the hounds right inside the sett where the fox had gone to ground, and we split the sab group to keep an eye on the sett and the hunt for the remainder of the day, getting locals to check throughout the evening and the next morning*.

* when doing so, you don’t want to prevent the fox from bolting and going elsewhere – open any blocked entrances, remove any nets from them and keep a safe distance

Step 3: Get in there

Sometimes all it takes is some knowledge of the law, confidence and a camera or two and you can sab a dig-out on arrival. The Ledbury terriermen in January 2015 quickly removed the terriers from the area and left when they knew they were on camera and had no excuse as to why they were about to dig a badger sett. The sabs present had quickly got on the phone to the police which probably helped the terriermen to make this decision.

Unfortunately this isn’t guaranteed to work every time (although having cameras present and recording is something we would always advise) and you might need to get physically involved in preventing the dig-out from occurring. Ideally, you need to get involved before the terriers have been entered – the terrier and the fox may fight and sometimes terriers won’t come out and the terriermen have to dig down to retrieve the terrier. Of course the law says that they should be under sufficient control, but this doesn’t mean it is always the case in reality. Even if terriers have already been entered, it doesn’t mean it’s all over, so you can still get involved.

You may be confronted with aggression from the terriermen, so always use your discretion – you might decide that all you can do is call the police and record what is going on – you can only do what you’re comfortable with. The following video shows West Midlands Hunt Sabs dealing with a dig-out in progress at the Atherstone Hunt in February 2015 with sabs physically sitting in and laying down across the entrances to prevent the terriermen being able to get to them.

Sheffield Sabs have the following videos posted online of attempted dig-outs which may show what the situation is like more clearly – the first one is of the terriermen trying to dig out a badger sett and the kind of attitudes you may come across with the terriermen and their supporters. The second video is of ‘Northern hunt sabs’ and is of an attempted dig-out of a fox at Escrick Park in November 2011.

It’s not all about confrontation, however, and we’ve had a lot of success in our early-morning sett-blocking patrols. Obviously we’d like to catch those responsible for blocking setts, but at the very least, we unblock several a day prior to the hunt meet which allows foxes more opportunity to escape below ground and. It is a lot easier to catch terriermen trying to dig-out at a sett than it is to gather enough evidence of illegal hunting as the fox is forced to run for miles when all escape options are blocked.

We’re working on getting more people out and about, checking setts before work or looking for blocked setts after tip-offs about hunt meets in certain areas or ‘dog-walking’ near to where the hunt will be during the day. This large sett was found blocked in December 2016 and unblocked along with various others just hours before the hounds arrived.

Useful links

There are many resources out there for information, but in terms of information you may need out in the field (regardless of which side of the argument you are on), the following are useful links to the law:

www.legislation.gov.uk: ‘Protection of Badgers Act 1992’, the ‘Hunting Act 2004’, the ‘Protection of Animals Act 1911’ and others

www.gov.uk/quad-bikes-the-rules

And, for their own rules and other information…

www.terrierwork.com (National Working Terrier Federation)

www.mfha.org.uk (Masters of Foxhounds Association)